Enough of the Outrage

What follows is my brief sermon from this past Friday night addressing our feelings about the conclusion of the impeachment proceedings as well as those about the prior week's unveiling of a new Mideast peace plan.

First and foremost, we are a nation of laws. And whether you thought the Democrats, or the Republicans were on the right side of history, the law and in particular the constitution is what governs our society. We can disagree about policies, about ideology, about what’s best or what’s worst for this country, but we must never forget it is the law that allows us to be one United States of America. It is a devotion to certain ideas that makes us a nation and those are enshrined in our constitution.

Second, regarding the peace plan again there are some reasonable takeaways. What this plan manages to do is to elevate Israel’s legitimate security needs and say that they must be held alongside the Palestinian’s desire, and right, for a state of their own. For too long, perhaps, peace plans sought to primarily undo injustices felt by the Palestinians rather than giving equal voice to Israelis desire to live in safety and security. For too long Palestinians’ refusal to come to the table has been excused and Israel’s march towards annexing the territories has been highlighted. To be sure, annexing the territories would be devastating for Israel’s democratic ideals. But Palestinian leaders need to come to the table and argue their case. Enough with the being outraged. Perhaps this plan can help move us forward.

As my teacher Yossi Klein Halevi argues that this plan has effectively exposed myths long held by both sides. He writes,

The Israeli myth is that the status quo can be indefinitely sustained and that the international community, distracted by more immediate tragedies in the Middle East, is losing interest in the Palestinian issue. But the Trump administration’s considerable investment of energy and prestige in devising its plan has reminded Israelis that the conflict cannot be wished away.

Regarding the other side, Halevi writes,

The Trump plan also challenges a key premise on the Palestinian side – that Palestinian leaders can continue to reject peace plans without paying a political price… It is long past time for Palestinian leaders to do what they have never done in the history of this conflict – offer their own detailed peace plan. We know what Palestinian leaders oppose – but what exactly do they support?That is my hope on all accounts on this Shabbat. Enough of the outrage. Get down to talking and arguing about how we are going to move forward. Let’s stop pointing fingers at how bad the other side is or how outraged they make us feel. Peace is in everyone’s interest. The rule of law is what allows societies to thrive.

Save the shouts not for our political opponents but instead for perhaps some good old-fashioned miracles. Take a cue from this week’s Torah portion. Moses, Miriam, and all the Israelites took their timbrels in their hands, started dancing with great joy, and most of all began to sing. They prayed, “Sing to the Lord, for God has triumphed gloriously.”

Perhaps this is the advice we most need. Calm down and sing a song. This is what this Shabbat evening might be best about. Sing. If we saved our shouts for something like that, we might be better served than shouting at each other and accusing one another of this outrage or that. I pray. Please God give us the strength to shout songs of joy in Your direction rather than shouts of outrage at one another.

Jump Into History

Yesterday Senator Mitt Romney said, “We are all footnotes at best in the annals of history.”

When the Jewish people approached the Sea of Reeds, with the Egyptian army pressing behind them, they feared that their liberation from slavery was a terrible mistake and that they would soon meet their deaths in the churning waves. According to tradition it was not their leader Moses’ outstretched arms that parted the seas. It was instead another man, named Nachshon.

Among rabbis, and historians, he is a well-known figure, but among many he is a forgotten footnote to our most famous tale. Looking around him at the fear among his fellow Israelites, seeing the doubt written across their faces about the journey upon which they had just embarked, Nachshon jumped into the waters.

“Nachshon has lost his mind,” the people shouted. “He is most certainly going to drown. Let us look away.” Meanwhile most of the Israelites could only see Moses standing above the crowd, arms outstretched to the heavens. Nachshon struggled in the sea’s waves, fighting to keep his head above the water. And then, just as the waters reached up to his neck, a miracle occurred. The seas parted. The people crossed on dry land.

We know this part of the story. The people broke out in song. They sang, “Mi chamochah ba-eilim, Adonai—Who is like you O God, among the gods that are worshipped!” (Exodus 15)

The few who witnessed Nachshon’s daring act, muttered to themselves about his gumption. Some lamented his contrarian spirit. (And I admit I am partial to such a spirit that swims against the currents—both literally and figuratively.) Others praised his faith. A few offered private words of thanks for his chutzpah. The majority, however, never discovered his name or found out that it was his solitary act which provided the required salvation and allowed the people to move forward toward freedom.

Sometimes the most important act of the day is a footnote.

I realized. Everyone knows Moses’ name. More should know Nachshon’s.

Perhaps we should reread our books beginning with such footnotes. Perhaps we should tell our histories beginning with these forgotten tales.

They may very well provide a way toward freedom.

When the Jewish people approached the Sea of Reeds, with the Egyptian army pressing behind them, they feared that their liberation from slavery was a terrible mistake and that they would soon meet their deaths in the churning waves. According to tradition it was not their leader Moses’ outstretched arms that parted the seas. It was instead another man, named Nachshon.

Among rabbis, and historians, he is a well-known figure, but among many he is a forgotten footnote to our most famous tale. Looking around him at the fear among his fellow Israelites, seeing the doubt written across their faces about the journey upon which they had just embarked, Nachshon jumped into the waters.

“Nachshon has lost his mind,” the people shouted. “He is most certainly going to drown. Let us look away.” Meanwhile most of the Israelites could only see Moses standing above the crowd, arms outstretched to the heavens. Nachshon struggled in the sea’s waves, fighting to keep his head above the water. And then, just as the waters reached up to his neck, a miracle occurred. The seas parted. The people crossed on dry land.

We know this part of the story. The people broke out in song. They sang, “Mi chamochah ba-eilim, Adonai—Who is like you O God, among the gods that are worshipped!” (Exodus 15)

The few who witnessed Nachshon’s daring act, muttered to themselves about his gumption. Some lamented his contrarian spirit. (And I admit I am partial to such a spirit that swims against the currents—both literally and figuratively.) Others praised his faith. A few offered private words of thanks for his chutzpah. The majority, however, never discovered his name or found out that it was his solitary act which provided the required salvation and allowed the people to move forward toward freedom.

Sometimes the most important act of the day is a footnote.

I realized. Everyone knows Moses’ name. More should know Nachshon’s.

Perhaps we should reread our books beginning with such footnotes. Perhaps we should tell our histories beginning with these forgotten tales.

They may very well provide a way toward freedom.

The Darkness of Auschwitz

We begin with the eighth plague of locusts. This is followed by the penultimate plague of darkness.

I wonder. What is so terrible about locusts? I discovered. It was not just a few locusts that found their way into a basement or through a crack in the window. Instead it was a swarm. A locust swarm, can measure over one square kilometer and can contain 50 million insects. These locusts can eat as much as 100,000 tons of vegetation in one day. Oy gevalt!

Following this devastation Egypt is covered with darkness.

It was no ordinary darkness. It was not a nighttime sky illuminated by the moon and stars. Instead it was pitch black. People could not even see their own hands when held in front of their eyes.

Some commentators suggest that the darkness should be likened to a psychological melancholy. How else do we explain that the Egyptians did not even light candles? It was instead darkness that even artificial illumination could not dispel. Imagine the fear. Shrouded in darkness the Egyptians remembered the plagues. They were alone with the incessant hum of millions upon millions of devouring locusts. Before their eyes, they could only see images of devastated fields, and ruined cities. They could see nothing but their losses.

We too are living in the shadow of such devastation. Similar images shroud our memories.

This week we marked the seventy fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. This place was created for one purpose alone. To devastate—the Jewish people. To murder—Jews in particular.

The Holocaust devoured millions. And so we likewise inhabit the ninth plague’s darkness. We close our eyes and see only destruction. We hear millions of names, children and elderly, men and women, devout and atheists, artists and laborers. All of those taken from their homes, uprooted from the countries of their birth and murdered for one reason alone. They were Jews.

The Holocaust darkens our view.

Auschwitz continues to command our attention. In fact, the contemporary Jewish philosopher, Emil Fackenheim, argues that Auschwitz offers a commanding voice, akin to Mount Sinai. He posits a 614th commandment, a singular mitzvah added to the tradition’s 613. We must survive. We must persevere. We must be steadfast in our faith. We must not lose hope in God. We have a sacred obligation to survive as Jews.

This commanding presence sometimes darkens our view of the world. We are forever suspect of world powers, of others, most especially their intentions and designs. We see a potential Holocaust around every turn. We must be forever on guard. We think, we must look out for ourselves first and foremost. This view is understandable given this history—only seventy five years in the past. This view seems more apropos given the rise in antisemitic attacks.

Then again, I am haunted by the words of other philosophers, most notably Richard Rubenstein, who argued that after Auschwitz anything is possible. We turn the pages of our newspapers, flipping from one atrocity to another. We have become inured to suffering and devastation. Within our very own country, there is devastation. Along our borders there is suffering, and pain. We turn away.

The United States Holocaust Museum continues its tracking of genocides. It catalogs a litany of countries, and situations, where genocides might emerge. How can this still be possible? Auschwitz was of course unique, but the likes of it should never again happen to us or to any people. And yet it has. In Cambodia. In Rwanda. In Bosnia-Herzegovina. And now, once again, in Myanmar.

We continue fumbling through the darkness.

We are hardened to the suffering of others. We are ever attuned to the threats facing us. Is it possible to find a way forward? Can we find our way through this ninth plague without inviting an even more devastating final plague?

Not every act of hatred is a potential Holocaust. And yet the world forgets the lessons of Auschwitz. Not every recognition of other people’s suffering is a betrayal of the Holocaust’s memory. And yet antisemitism has once again become murderous.

Perhaps where the Egyptians failed, we can succeed. We must recognize that we still live in the shadows of this plague. We must acknowledge that this darkness still colors our view.

Then we might find one candle to illuminate a path forward.

I wonder. What is so terrible about locusts? I discovered. It was not just a few locusts that found their way into a basement or through a crack in the window. Instead it was a swarm. A locust swarm, can measure over one square kilometer and can contain 50 million insects. These locusts can eat as much as 100,000 tons of vegetation in one day. Oy gevalt!

Following this devastation Egypt is covered with darkness.

It was no ordinary darkness. It was not a nighttime sky illuminated by the moon and stars. Instead it was pitch black. People could not even see their own hands when held in front of their eyes.

Some commentators suggest that the darkness should be likened to a psychological melancholy. How else do we explain that the Egyptians did not even light candles? It was instead darkness that even artificial illumination could not dispel. Imagine the fear. Shrouded in darkness the Egyptians remembered the plagues. They were alone with the incessant hum of millions upon millions of devouring locusts. Before their eyes, they could only see images of devastated fields, and ruined cities. They could see nothing but their losses.

We too are living in the shadow of such devastation. Similar images shroud our memories.

This week we marked the seventy fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. This place was created for one purpose alone. To devastate—the Jewish people. To murder—Jews in particular.

The Holocaust devoured millions. And so we likewise inhabit the ninth plague’s darkness. We close our eyes and see only destruction. We hear millions of names, children and elderly, men and women, devout and atheists, artists and laborers. All of those taken from their homes, uprooted from the countries of their birth and murdered for one reason alone. They were Jews.

The Holocaust darkens our view.

Auschwitz continues to command our attention. In fact, the contemporary Jewish philosopher, Emil Fackenheim, argues that Auschwitz offers a commanding voice, akin to Mount Sinai. He posits a 614th commandment, a singular mitzvah added to the tradition’s 613. We must survive. We must persevere. We must be steadfast in our faith. We must not lose hope in God. We have a sacred obligation to survive as Jews.

This commanding presence sometimes darkens our view of the world. We are forever suspect of world powers, of others, most especially their intentions and designs. We see a potential Holocaust around every turn. We must be forever on guard. We think, we must look out for ourselves first and foremost. This view is understandable given this history—only seventy five years in the past. This view seems more apropos given the rise in antisemitic attacks.

Then again, I am haunted by the words of other philosophers, most notably Richard Rubenstein, who argued that after Auschwitz anything is possible. We turn the pages of our newspapers, flipping from one atrocity to another. We have become inured to suffering and devastation. Within our very own country, there is devastation. Along our borders there is suffering, and pain. We turn away.

The United States Holocaust Museum continues its tracking of genocides. It catalogs a litany of countries, and situations, where genocides might emerge. How can this still be possible? Auschwitz was of course unique, but the likes of it should never again happen to us or to any people. And yet it has. In Cambodia. In Rwanda. In Bosnia-Herzegovina. And now, once again, in Myanmar.

We continue fumbling through the darkness.

We are hardened to the suffering of others. We are ever attuned to the threats facing us. Is it possible to find a way forward? Can we find our way through this ninth plague without inviting an even more devastating final plague?

Not every act of hatred is a potential Holocaust. And yet the world forgets the lessons of Auschwitz. Not every recognition of other people’s suffering is a betrayal of the Holocaust’s memory. And yet antisemitism has once again become murderous.

Perhaps where the Egyptians failed, we can succeed. We must recognize that we still live in the shadows of this plague. We must acknowledge that this darkness still colors our view.

Then we might find one candle to illuminate a path forward.

How Can We Hear What Might Help Us?

God summons Moses and tells him of the plan to free the Israelites from slavery and lead them to the Promised Land, but “when Moses told this to the Israelites, they would not listen to Moses, their spirits crushed by cruel bondage.” (Exodus 6)

The Hebrew for “spirits crushed” is kotzer ruach. The word ruach can in fact mean spirit, wind or breath. Kotzer comes from the Hebrew meaning shortened or stunted. And so the medieval commentator, Rashi (eleventh century), suggests that the Israelites did not listen. Why? Because they experienced “shortness of breath.” They were tired and could not catch their breath. The physical toll of years of servitude had made the Israelites so tired they could not even hear when Moses tells them they will soon go free. This makes sense. Sometimes it is impossible to listen to others, or even to hear wonderful news, when one is tired.

Physical health influences the mind. Exhaustion colors our mood. Good news, and bad news, is lost on those who are utterly tired. They cannot hear because they only want to rest. Is this why the plagues were necessary? They were not so much about punishing the Egyptians. Instead their purpose was to awaken the Israelites to God’s majesty and power. Such is Rashi’s understanding of this phrase.

Another commentator, Ramban (thirteenth century), suggests that this phrase should be read as “shortness of spirit.” He argues that the Israelites were impatient. They did not listen to Moses and could not hear God’s promises because they were impatient. This too is a truism. When people are impatient, thinking about whatever else they might have on their agendas they fail to pay attention to the important words standing right before their eyes.

How many times have we said to ourselves, “I wish he would hurry up and finish talking. I am already late for my dinner date.” We might then miss some important news. How many times do we skim over our emails and text messages while waiting impatiently at a red light only to discover we missed the important bit of news at the end of the email chain?

Impatience and exhaustion interfere with true listening.

I prefer however to read this phrase as “their spirits were stunted.” Why? Because their suffering made them unable to hear anything but their own pain. When we are experiencing pain, we are unable to pay attention to other people’s tzuris or sometimes, are even unable to hear good news. The words can be about our very own redemption and we still cannot hear them. Moses offered the Israelites words that foretold their own salvation and yet they could not see beyond their own pain.

It is not that they were stubborn and would not listen but instead that they could not hear. Their suffering and pain obscured their hearing.

The question still confronts us. How can we see beyond our own tzuris, and our pains, and hear the words that might offer our own salvation? It should not require miracles, or plagues visited upon others, to open our eyes to wonders and ears to saving words.

Perhaps it is as simple as hearing our own breath. Perhaps it is as obvious as opening our spirit to God’s plan. All we need to do is lengthen our spirits and expand our hearing.

Someone could indeed be standing right before us and offering us words of salvation and redemption.

The Hebrew for “spirits crushed” is kotzer ruach. The word ruach can in fact mean spirit, wind or breath. Kotzer comes from the Hebrew meaning shortened or stunted. And so the medieval commentator, Rashi (eleventh century), suggests that the Israelites did not listen. Why? Because they experienced “shortness of breath.” They were tired and could not catch their breath. The physical toll of years of servitude had made the Israelites so tired they could not even hear when Moses tells them they will soon go free. This makes sense. Sometimes it is impossible to listen to others, or even to hear wonderful news, when one is tired.

Physical health influences the mind. Exhaustion colors our mood. Good news, and bad news, is lost on those who are utterly tired. They cannot hear because they only want to rest. Is this why the plagues were necessary? They were not so much about punishing the Egyptians. Instead their purpose was to awaken the Israelites to God’s majesty and power. Such is Rashi’s understanding of this phrase.

Another commentator, Ramban (thirteenth century), suggests that this phrase should be read as “shortness of spirit.” He argues that the Israelites were impatient. They did not listen to Moses and could not hear God’s promises because they were impatient. This too is a truism. When people are impatient, thinking about whatever else they might have on their agendas they fail to pay attention to the important words standing right before their eyes.

How many times have we said to ourselves, “I wish he would hurry up and finish talking. I am already late for my dinner date.” We might then miss some important news. How many times do we skim over our emails and text messages while waiting impatiently at a red light only to discover we missed the important bit of news at the end of the email chain?

Impatience and exhaustion interfere with true listening.

I prefer however to read this phrase as “their spirits were stunted.” Why? Because their suffering made them unable to hear anything but their own pain. When we are experiencing pain, we are unable to pay attention to other people’s tzuris or sometimes, are even unable to hear good news. The words can be about our very own redemption and we still cannot hear them. Moses offered the Israelites words that foretold their own salvation and yet they could not see beyond their own pain.

It is not that they were stubborn and would not listen but instead that they could not hear. Their suffering and pain obscured their hearing.

The question still confronts us. How can we see beyond our own tzuris, and our pains, and hear the words that might offer our own salvation? It should not require miracles, or plagues visited upon others, to open our eyes to wonders and ears to saving words.

Perhaps it is as simple as hearing our own breath. Perhaps it is as obvious as opening our spirit to God’s plan. All we need to do is lengthen our spirits and expand our hearing.

Someone could indeed be standing right before us and offering us words of salvation and redemption.

Our Story is Not Just About Us

I am thinking of the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights struggle that continues to this day.

This week the Torah reminds me that the redemption from slavery began when God takes note of the Israelites’ suffering. 400 years of slavery comes to an end when the pain is finally noticed.

“God heard their moaning, and God remembered the covenant with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob.” (Exodus 2)

Maya Angelou, the great contemporary American poet, stirs my heart with the words:

“God looked upon the Israelites, and God took notice of them.”

When will we follow God’s example? When will we begin to take notice?

We too can say:

This week the Torah reminds me that the redemption from slavery began when God takes note of the Israelites’ suffering. 400 years of slavery comes to an end when the pain is finally noticed.

“God heard their moaning, and God remembered the covenant with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob.” (Exodus 2)

Maya Angelou, the great contemporary American poet, stirs my heart with the words:

Out of the huts of history’s shameI return to the Torah. It reminds and cajoles. Perhaps all it takes is for us to take note of the suffering and pain.

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

“God looked upon the Israelites, and God took notice of them.”

When will we follow God’s example? When will we begin to take notice?

We too can say:

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

Take note. Rise up.

Our march from slavery to freedom is not just about us.

Our march from slavery to freedom is not just about us.

How to Fight Antisemitism and How to Not

I marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in Sunday's Solidarity March because we face unprecedented times. Most of us have never experienced this level

of antisemitism and most especially the violence that has accompanied recent

attacks. We are struggling to make sense

of this increase in antisemitic hate and violence. And so I would like to offer some advice and

guidance for how we might approach these times and how we might fortify our

souls.

1. We must fight antisemitism

wherever, and whenever, it appears. We

must expose it. We must label it as

hate. We must never be deterred. Support the many Jewish organizations that

help to lead this fight, in particular but not exclusively the Anti-Defamation

League and the American Jewish Committee.

2. We must not pretend that antisemites only target other Jews. We must never say things like ultra-Orthodox

Jews, like those in Monsey, were targeted because they separate themselves from

the larger, American society. Just

because someone visibly identifies as a Jew and just because we have the luxury

of taking our kippah off does not mean we should give ourselves the permission

of separating ourselves from other Jews.

We are one people whether we acknowledge this or not. Antisemites make no distinction between

Jews. We should not, we must not, as

well.

3. We must not allow the fight against antisemitism to divide us. We must stop seeing this struggle through

our partisan lenses. Stop saying it’s

all because of this person or that, this leader or that politician. There is

plenty of blame to go around. There is

plenty of fault to be found with Democratic leaders and Republican

politicians. Can we at the very least

get on the same team in our fight against antisemitism? Do you think antisemites care who you voted

for or who you voted against? Again, we

are one people and we are in this together, Reform and Orthodox, Republican and

Democrat, synagogue going and synagogue denying. Fight the tendency to see each and every

antisemitic incident as proof of your political leanings and ask yourself

instead, what more can I do to protect the Jewish people, my people? Let’s stop fighting with each other and start

banding together to fight antisemites.

4. We must not be afraid. We must

not allow rising antisemitism, and in particular these recent violent attacks,

to make us constantly afraid. Of course

we should be cautious, but fear and caution and very different things. The latter is about making reasoned and

judicious decisions (by the way, we have an expert security company at the

synagogue who looks out for our safety and well-being). The former is about emotions. If everything is guided by the emotions of fear

then we will never do anything new again.

We will never talk to a new person or make a new friend or venture to a

new destination. Yes, the world is a

dangerous place, but it is also a wonderful place. And seeing that wonder, amidst all these

terrors, is a matter of belief and something that you can train yourself to

feel. I refuse to allow my soul to live

behind closed gates and doors. The

Jewish people have survived, and outlasted, far worse than our current

travails. Of course, it’s hard to gain this

historical perspective, or any perspective for that matter, when you are in the

midst of a fight but Jewish history should remind us that while antisemites have

often been arrayed against us, we have always persevered. Have faith!

5. We must not allow antisemitism to define us. We are Jewish not because of the names they

call us or what they say about us, but because we belong to an extraordinary

tradition that affirms life and provides meaning to our days. Our rabbis remind us that it is a commandment

to rejoice. It is a mitzvah to dance

with a bride and groom, for example. So

important is this communal obligation that it even takes precedence over the

demands of mourning. Rejoice! Shout God’s praises. Our tradition also offers blessings for

lightning and thunder. Imagine

that. That which conjures fear the

rabbis said we should instead find there the inspiration to offer praise and

thanks. There are many other examples I

could offer that might further illustrate this point, but let’s always recall

that we are Jewish because of the meaning and beauty Judaism offers us rather

than how we might respond to those who hate us.

Stay strong. Remain

focused. Have faith.

This week we conclude the reading of the book of

Genesis. Most of the time we look at

this book in the discrete units comprising the weekly portions. If we look at this first book of the Torah in

its entirety we find instead a remarkable teaching. The book begins with two brothers, Cain and

Abel. Cain of course kills Abel. We then follow the tensions between brothers

Isaac and Ishmael and Jacob and Esau. In

each successive tale the brothers come closer to repairing their fractured

relations but never fully realize repair and reconciliation. And then finally, at the conclusion of this

book, Joseph and his brothers are fully reconciled. Only a few weeks ago Joseph’s brothers wanted

to kill him. Now they forgive each other,

are reconciled, and live the remainder of their days in peace.

We must always have hope.

That is our tradition’s most important teaching. It was true then. It is also true now.

I Walked in the March Against Antisemitism to Reclaim Our Home

Don George, the preeminent travel writer, offers an insightful observation in The Way of Wanderlust: “Becoming vulnerable requires concentration, devotion, and a leap of faith–the ability to abandon yourself to a forbiddingly foreign place and say, in effect, ‘Here I am; do with me what you will.’ It’s the first step on the pilgrim’s path.”

American Jews have awakened to feelings of abandonment. Our home has become a foreign place. Antisemitism is no longer something that happens over there or something that occurred back then. It is here. It is now.

We debate the causes. It is because American leaders resort to language which demonizes minorities. We argue about the reasons. It is because university professors label our devotions colonial oppressions. We blame politicians–at least those who stand in opposition to our partisan commitments. We say it is because they are unwilling to stand with us or to fight alongside us. We debate with our fellow Jews–often even more vociferously–about their vote, telling them it is all because of who they voted for or who they plan to vote against. We hear, it is because of those Jews not our kind of Jews.

Jews are being murdered when they gather to sing Shabbat prayers. Jews are attacked when they come together to celebrate Hanukkah. Jews are killed when they go shopping for kosher chickens. Where? Here. In America.

What once felt like a welcoming home no longer makes us feel at home.

And so, on Sunday, I joined with my wife and daughter, and twenty-five thousand others and marched across the Brooklyn Bridge....

American Jews have awakened to feelings of abandonment. Our home has become a foreign place. Antisemitism is no longer something that happens over there or something that occurred back then. It is here. It is now.

We debate the causes. It is because American leaders resort to language which demonizes minorities. We argue about the reasons. It is because university professors label our devotions colonial oppressions. We blame politicians–at least those who stand in opposition to our partisan commitments. We say it is because they are unwilling to stand with us or to fight alongside us. We debate with our fellow Jews–often even more vociferously–about their vote, telling them it is all because of who they voted for or who they plan to vote against. We hear, it is because of those Jews not our kind of Jews.

Jews are being murdered when they gather to sing Shabbat prayers. Jews are attacked when they come together to celebrate Hanukkah. Jews are killed when they go shopping for kosher chickens. Where? Here. In America.

What once felt like a welcoming home no longer makes us feel at home.

And so, on Sunday, I joined with my wife and daughter, and twenty-five thousand others and marched across the Brooklyn Bridge....

Fake News and Real News

Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery and tell their father that a wild beast killed him. But Joseph soon manages to turn their evil act into good. He becomes ruler of Egypt, second only to Pharaoh. His intelligence and prescience, in particular his ability to interpret dreams, help him prepare Egypt for the impending famine. The Egyptians spend seven years storing food and when the famine arrives they have plenty to spare.

His brothers are forced to come to Egypt in search of food. Joseph gives them enough to eat and even more to take back home. He does not reveal his identity. He implements a careful plot in which he frames his brothers and accuses them of stealing to see if they will once again sell their brother Benjamin into slavery. They do not. Joseph reveals his identity. Amid tears, he stammers, “I am Joseph. Is my father still well?”

The brothers are dumbfounded. The revelation that their brother Joseph who they sold into slavery is now a powerful ruler stuns them. Joseph forgives his brothers and they are reconciled. He instructs them to go back to their father, Jacob, and tell him that he is still alive. Joseph wants the entire family to live together in Egypt. “The brothers went up from Egypt and came to their father Jacob in the land of Canaan. And they told him, ‘Joseph is still alive; yes, he is ruler over the whole land of Egypt.’ His heart stopped, for he did not believe them.” (Genesis 45)

Jacob’s heart stops when first hearing the news. The news nearly kills him. Some translations suggest it should instead read, “His heart went numb.” The Torah’s intention is definitive. The news is impossible for Jacob to comprehend. To believe it would mean that his other sons lied to him so many years ago.

At that time, when Jacob first heard their tale about Joseph’s fate, namely that he was killed by wild beasts, Jacob nearly dies. He says, “I will go down mourning to my son in Sheol (the place of the dead).” Now Jacob dies once again after hearing the shattering news. His son is alive.

His sons lied.

The Rabbis comment: “This is the fate of a liar; even when telling the truth, a liar is not believed. (Avot d’Rabbi Nathan 30)

I wonder. Can habitual liars ever be believed?

We live in an age when we are unable to even agree upon the facts. Each side of the political divide adheres to a different set of truths. They accuse the other of telling lies. Our hearts grow increasingly numb to truth. We remain trapped in between, unable to discuss, and even debate, solutions to the many problems, and dilemmas, we face because we are unable to agree on the underlying truths upon which any discussion, and reasoned debate, must begin. Instead we spend our time, and our energy, arguing about what is fake and what is real. Our debates spin around who is lying and who is telling the truth.

How can we navigate ourselves, and our nation, back to truth?

I continue to weep for Jacob. He endured so many years mourning for his beloved son. After discovering that Joseph lives, he must endure the knowledge that his other sons are liars. And yet, after some time, “the spirit of their father Jacob revived.” And he speaks:

“Enough!

My son Joseph is still alive! I must go and see him before I die.” (Genesis 45)

Truth endures.

His brothers are forced to come to Egypt in search of food. Joseph gives them enough to eat and even more to take back home. He does not reveal his identity. He implements a careful plot in which he frames his brothers and accuses them of stealing to see if they will once again sell their brother Benjamin into slavery. They do not. Joseph reveals his identity. Amid tears, he stammers, “I am Joseph. Is my father still well?”

The brothers are dumbfounded. The revelation that their brother Joseph who they sold into slavery is now a powerful ruler stuns them. Joseph forgives his brothers and they are reconciled. He instructs them to go back to their father, Jacob, and tell him that he is still alive. Joseph wants the entire family to live together in Egypt. “The brothers went up from Egypt and came to their father Jacob in the land of Canaan. And they told him, ‘Joseph is still alive; yes, he is ruler over the whole land of Egypt.’ His heart stopped, for he did not believe them.” (Genesis 45)

Jacob’s heart stops when first hearing the news. The news nearly kills him. Some translations suggest it should instead read, “His heart went numb.” The Torah’s intention is definitive. The news is impossible for Jacob to comprehend. To believe it would mean that his other sons lied to him so many years ago.

At that time, when Jacob first heard their tale about Joseph’s fate, namely that he was killed by wild beasts, Jacob nearly dies. He says, “I will go down mourning to my son in Sheol (the place of the dead).” Now Jacob dies once again after hearing the shattering news. His son is alive.

His sons lied.

The Rabbis comment: “This is the fate of a liar; even when telling the truth, a liar is not believed. (Avot d’Rabbi Nathan 30)

I wonder. Can habitual liars ever be believed?

We live in an age when we are unable to even agree upon the facts. Each side of the political divide adheres to a different set of truths. They accuse the other of telling lies. Our hearts grow increasingly numb to truth. We remain trapped in between, unable to discuss, and even debate, solutions to the many problems, and dilemmas, we face because we are unable to agree on the underlying truths upon which any discussion, and reasoned debate, must begin. Instead we spend our time, and our energy, arguing about what is fake and what is real. Our debates spin around who is lying and who is telling the truth.

How can we navigate ourselves, and our nation, back to truth?

I continue to weep for Jacob. He endured so many years mourning for his beloved son. After discovering that Joseph lives, he must endure the knowledge that his other sons are liars. And yet, after some time, “the spirit of their father Jacob revived.” And he speaks:

“Enough!

My son Joseph is still alive! I must go and see him before I die.” (Genesis 45)

Truth endures.

What's in a Name

Customarily we call people to the Torah using their Hebrew names. “Yaamod Shmaryah ben Tzemach v’Masha.” But we go about our days using our English names. “Stand up Steven Moskowitz.”

Except at synagogue, or perhaps at weddings and funerals, we rarely call people by their Hebrew names. So why are people surprised that our patriarch Joseph goes by an Egyptian name instead of the Hebrew name his parents gave him?

The Torah reports: “Pharaoh then gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-paneah.” (Genesis 41) In ancient Egyptian, this means “God speaks; he lives.” First Pharaoh appoints Joseph as his number two, in charge of shepherding Egypt through the impending famine. Then he gives him a proper Egyptian name, as well as a wife, by the way.

Like Joseph we live in two worlds. We carry two names. Our identities are hyphenated. American-Jew. Which name we rely on depends upon the circumstance. Do I identify as a Jew? Or should I be called by my American identity? It depends on who we are standing beside. It depends upon the environment.

The Israeli poet, Zelda, suggests it depends on even more. We have far more than just two names. She writes:

How do we wish to be known?

The rabbis offer an exclamation.

“The crown of a good name is superior to them all.” (Pirke Avot 4)

And that works in Hebrew or in English—and even in Egyptian—or any language for that matter.

It’s really all about earning a good name.

Except at synagogue, or perhaps at weddings and funerals, we rarely call people by their Hebrew names. So why are people surprised that our patriarch Joseph goes by an Egyptian name instead of the Hebrew name his parents gave him?

The Torah reports: “Pharaoh then gave Joseph the name Zaphenath-paneah.” (Genesis 41) In ancient Egyptian, this means “God speaks; he lives.” First Pharaoh appoints Joseph as his number two, in charge of shepherding Egypt through the impending famine. Then he gives him a proper Egyptian name, as well as a wife, by the way.

Like Joseph we live in two worlds. We carry two names. Our identities are hyphenated. American-Jew. Which name we rely on depends upon the circumstance. Do I identify as a Jew? Or should I be called by my American identity? It depends on who we are standing beside. It depends upon the environment.

The Israeli poet, Zelda, suggests it depends on even more. We have far more than just two names. She writes:

Everyone has a nameHer poem is beautiful in its simplicity. It is thought-provoking, and at times haunting. How many encounters, how many circumstances offer us new names? We are left wondering.

given to him by God

and given to him by his parents

Everyone has a name

given to him by his stature

and the way he smiles

and given to him by his clothing

Everyone has a name

given to him by the mountains

and given to him by his walls

Everyone has a name

given to him by the stars

and given to him by his neighbors

Everyone has a name

given to him by his sins

and given to him by his longing

Everyone has a name

given to him by his enemies

and given to him by his love

Everyone has a name

given to him by his feasts

and given to him by his work

Everyone has a name

given to him by the seasons

and given to him by his blindness

Everyone has a name

given to him by the sea and

given to him

by his death.

How do we wish to be known?

The rabbis offer an exclamation.

“The crown of a good name is superior to them all.” (Pirke Avot 4)

And that works in Hebrew or in English—and even in Egyptian—or any language for that matter.

It’s really all about earning a good name.

Let's Be Proud...and Be Careful

Although the true history of Hanukkah recounts a bloody

civil war between Jewish zealots led by Judah Maccabee with their fellow Jews enamored

of Greek culture, we prefer to tell the story of the miracle of oil. Here is that idealized version.

A long time ago, approximately 2,200 years before our

generation, the Syrian-Greeks ruled much of the world and in particular the

land of Israel. Their king, Antiochus,

insisted that all pray and offer sacrifices as he did. He outlawed Jewish practice and desecrated

the holy Temple. But our heroes, the

Maccabees, rebelled against his rule.

After nearly three years of battle, the Maccabees prevailed. They recaptured the Temple.

When the Jews entered the Temple, they were horrified to

discover that their holiest of shrines had been transformed and remade to suit pagan

worship. They declared a dedication (the

meaning of hanukkah) ceremony. Soon

they discovered that there was only enough holy oil to last for one of the

eight day long ceremony. Still they lit

the menorah that adorned the sanctuary.

And lo and behold, a great miracle happened there. The oil lasted not for the expected single

day but for all eight days.

The rabbis therefore decreed that we should light Hanukkah

candles on each of this holiday’s nights, beginning on the first evening, on

the twenty fifth of Kislev. (The customs

of spinning dreidels and eating foods fried in oil came much later.) The rabbis pronounced: “It is a mitzvah to place the Hanukkah lamp at the entrance to one’s house on

the outside, so that all can see it. If a person lives upstairs, he places it at the window most adjacent to

the public domain.” (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 21b)

Contrary to the

contemporary ethic of privacy where what we do in our own homes is not to be

publicized to the outside world, the rabbis instruct us that we must display

the menorah so that others may see it.

Why? So that the world might also

learn about the miracle of Hanukkah. So

that others might see that God performs wonders.

Are not our Jewish

identities meant to be hidden? No, the

rabbis declare. They are intended to be

proclaimed to the world. Even though

everyone else appears to be celebrating other holidays at this time of year, we

reaffirm that we have our own unique faith, and that we are proud to publicize

it. The rabbis counsel that we should

proudly proclaim our Jewish faith—at least during the eight days of

Hanukkah. That is the message of the

Maccabees. That is the import of their

revolt against those who wished to suppress Jewish practice.

But what happens if Jews

live in a time and place when placing the menorah in their windows could be

dangerous? The rabbis decree: “And

in a time of danger he places it on the table and that is sufficient to fulfill

his obligation.” What should we do now? Where should we place the menorah today? Is our own era a time of danger?

Recently I met with a friend who was visiting from

Israel. He told me that he now covers

his kippah with a baseball hat when going out to restaurants in New York. He is afraid.

I heard as well of young couples who second guess their decision to send

their children to a Jewish nursery school for fear that it could be a target of

antisemitic attacks. After years of

increasing attacks, after the most recent Jersey City murders and the assault

at Indiana University to name a few, fear has come to dominate our discussions

of Jewish identity. Where is it safe to

declare our Jewishness?

Should we hide our identity?

Can the Talmud, and Jewish tradition, help us to figure out what

constitutes a real danger? Later

authorities suggest that the rabbis understood danger to mean when Jewish practice

is outlawed, such as during the Maccabean revolt. Only then should we move our menorahs to “safer

ground.” But who gets to decide what

dangerous means? Our rabbis? Our tradition?

Instead it is each of us. Danger is of course a matter of

perception. It is in truth more about

feelings than threats. If a person is afraid,

then the threat is real.

I have been thinking that perhaps my frequent trips to

Israel have provided me with some helpful measures of strength and resolve. The modern era grants us something that our

ancient rabbis could never have imagined: a sovereign Jewish state, a state

that can fight back against our enemies.

We look to a state that can fortify us and offer us even greater courage

in the face of this growing tide of antisemitic hate.

This is why I found it so surprising that it was my Israeli

friend who now expresses fear. Perhaps

it is even more a matter of where one feels at home. If we feel at home we are less likely to feel

afraid.

Today we are called once again to fight back against

antisemitism. Our day demands that we

never allow this hate even the space to breathe. We must stand up. We must be forever proud. But we must also be prudent. The rabbis’ caution is well taken.

The most important point of course is that regardless of

where we decide to place the menorah, regardless of whether or not we are

afraid, we light the candles. Find that

place. Find the place where you are

comfortable proudly declaring your Jewish faith. And there light the menorah. This year most especially, this holiday of

Hanukkah demands no less.

The Kiss of Reconciliation

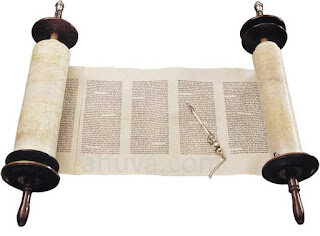

The Torah scroll is beautifully calligraphed. Each of its letters is meticulously drawn. It takes a Torah scribe one year to fashion a single scroll. Some letters have small, stylized crowns. The chapters and verses are perfectly arranged in columns, unfettered by punctuation marks. Although each scroll is different because it is fashioned by a different scribe, the letters and words of every Torah are calligraphed in a similar manner.

“Moses” looks the same in every Torah scroll. There is the mem, the first letter of Moshe. Then the shin, adorned with its crowns, and finally the heh. Like all the other words in the Torah, there are no vowels below the letters or cantillation marks above the letters. In fact, only a very small fraction of words in the Torah have additional notations.

Very few words have marks above the letters. This week we discover one of these unique examples: “Vayishakeyhu—and he kissed him.” Calligraphed above each of its letters is a dot. Here is the story that surrounds this kiss. Our forefather Jacob stole the birthright from his brother Esau. Esau then threatened to kill him. Jacob runs and builds a life for himself with his uncle. He marries (several times) and fathers many children. Now, many years later, the brothers are to be reunited, and we hope, reconciled.

This week we read, “Jacob himself went on ahead and bowed low to the ground seven times until he was near his brother. Esau ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept.” (Genesis 33) The brothers appear reconciled. What led to the reconciliation? Was it Jacob’s act of humbling himself before his brother? Was it Esau’s embrace? The seventh century Masoretes, who developed the traditions of calligraphy with which a Torah is scribed, suggest it was the kiss.

Holding his brother close, Esau kissed Jacob and kissed him again and again, until they both wept. The Rabbis concur: “The word ‘kissed’ is dotted above each letter in the Torah’s writing. Rabbi Simeon ben Elazar said: this teaches that Esau felt compassion in that moment and kissed Jacob with all his heart. (Bereshit Rabbah) Reconciliation can only be achieved when people bring their heart—in its entirety. Repair involves compassion for the other. It necessitates forgiveness. And these must derive from the heart.

A kiss can be perfunctory. The Torah’s calligraphy suggests that, in this case it is anything but. A kiss should be punctuated by intention. Here it offers the compassion and forgiveness that leads to the weeping of reconciliation. The brothers stand together.

We are of course the descendants of Jacob. The tradition teaches that our enemies are the descendants of Esau. I wonder if our ancient calligraphers intended to teach that reconciliation between brothers is our most cherished hope and prayer.

Why else would they notate this word in a different manner than all other words?

Embedded in the kiss Esau offers Jacob is our tradition’s hope that the descendants of Esau will one day make peace with the descendants of Jacob. One day, we pray, we might make peace with our enemies, who, our tradition reminds us, are, and will always be, our brothers.

The Torah wishes to punctuate this hope for reconciliation and repair. One day brothers, and all humanity, will be at peace with each other.

And we will embrace, kiss, and finally weep as one family.

“Moses” looks the same in every Torah scroll. There is the mem, the first letter of Moshe. Then the shin, adorned with its crowns, and finally the heh. Like all the other words in the Torah, there are no vowels below the letters or cantillation marks above the letters. In fact, only a very small fraction of words in the Torah have additional notations.

Very few words have marks above the letters. This week we discover one of these unique examples: “Vayishakeyhu—and he kissed him.” Calligraphed above each of its letters is a dot. Here is the story that surrounds this kiss. Our forefather Jacob stole the birthright from his brother Esau. Esau then threatened to kill him. Jacob runs and builds a life for himself with his uncle. He marries (several times) and fathers many children. Now, many years later, the brothers are to be reunited, and we hope, reconciled.

This week we read, “Jacob himself went on ahead and bowed low to the ground seven times until he was near his brother. Esau ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept.” (Genesis 33) The brothers appear reconciled. What led to the reconciliation? Was it Jacob’s act of humbling himself before his brother? Was it Esau’s embrace? The seventh century Masoretes, who developed the traditions of calligraphy with which a Torah is scribed, suggest it was the kiss.

Holding his brother close, Esau kissed Jacob and kissed him again and again, until they both wept. The Rabbis concur: “The word ‘kissed’ is dotted above each letter in the Torah’s writing. Rabbi Simeon ben Elazar said: this teaches that Esau felt compassion in that moment and kissed Jacob with all his heart. (Bereshit Rabbah) Reconciliation can only be achieved when people bring their heart—in its entirety. Repair involves compassion for the other. It necessitates forgiveness. And these must derive from the heart.

A kiss can be perfunctory. The Torah’s calligraphy suggests that, in this case it is anything but. A kiss should be punctuated by intention. Here it offers the compassion and forgiveness that leads to the weeping of reconciliation. The brothers stand together.

We are of course the descendants of Jacob. The tradition teaches that our enemies are the descendants of Esau. I wonder if our ancient calligraphers intended to teach that reconciliation between brothers is our most cherished hope and prayer.

Why else would they notate this word in a different manner than all other words?

Embedded in the kiss Esau offers Jacob is our tradition’s hope that the descendants of Esau will one day make peace with the descendants of Jacob. One day, we pray, we might make peace with our enemies, who, our tradition reminds us, are, and will always be, our brothers.

The Torah wishes to punctuate this hope for reconciliation and repair. One day brothers, and all humanity, will be at peace with each other.

And we will embrace, kiss, and finally weep as one family.

Finding Our Shul and Our Path

Among my favorite, and often quoted, books is Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost. (The title alone is enough to get me to pick it up again and again.) Solnit offers a number of observations about travel, nature, science and discovering ourselves. She begins: “Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go.” The question is the beginning of apprehension. (And this is exactly why apprehension has two meanings.) Journeying, and the curiosity that must drive it, leads to wisdom.

Uncertainty is where real learning begins.

Our hero Jacob stands at the precipice of an uncertain time. He is running from home. He has just tricked his brother Esau out of his birthright. Esau has promised to kill him. Their mother, Rebekah, urges Jacob to leave and go to her brother, Laban. Their father Isaac instructs him, “Get up! Go to Paddan-Aram.”

Jacob is alone. He wanders the desert wilderness. Soon he stops for the night. Jacob dreams. He sees angels climbing a ladder that reaches to heaven. He hears God’s voice saying, “I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham, and your father Isaac. Remember. I am with you.” (Genesis 28). Jacob awakes. He recognizes God’s presence. He has found God in this desolate, and non-descript landscape. He exclaims, “How awesome is this place. This is none other than beth-el, the house of God.”

Rebecca Solnit again. She leans on Tibetan wisdom: “Emptiness is the track on which the centered person moves.” Is it possible, I wonder, that a journey precipitated by feelings of anxiety, bewilderment, and even abandonment (I imagine our forefather thought, “Now my brother wants to kill me. My father tells me to get out. Where am I to go? What am I to do?”) leads to finding one’s bearings? Jacob’s uncertain path is becoming clearer.

In Tibetan, the word for path is “shul.” Solnit continues:

How does our shul not become an “impression of something that used to be there”? If synagogue is only about our imaginations of yesterday, then how do we carve our own path? If authenticity is only driven by what we believe our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents did, and did not do, then how do we create our own impression, in our own image? Too much of what we expect, and want, from our synagogues revolves around the question of how they honor the past. “There is not enough Hebrew at that synagogue” is, for example, a common refrain.

I am thinking. How can we carve a path while looking backward? How do we find our way when looking back, at some impression of yesteryear? How then do we find our own shul?

It is not just a building. It is not as well a destination. It cannot only be the impression made by others, long ago.

It is instead a path.

Jacob awakes, startled, but perhaps more aware. He exclaims, “Surely the Lord is present in this place.”

Where?

Exactly where you are standing.

Just leave the door open.

And heed the voice.

Get up. Go.

Uncertainty is where real learning begins.

Our hero Jacob stands at the precipice of an uncertain time. He is running from home. He has just tricked his brother Esau out of his birthright. Esau has promised to kill him. Their mother, Rebekah, urges Jacob to leave and go to her brother, Laban. Their father Isaac instructs him, “Get up! Go to Paddan-Aram.”

Jacob is alone. He wanders the desert wilderness. Soon he stops for the night. Jacob dreams. He sees angels climbing a ladder that reaches to heaven. He hears God’s voice saying, “I am the Lord, the God of your father Abraham, and your father Isaac. Remember. I am with you.” (Genesis 28). Jacob awakes. He recognizes God’s presence. He has found God in this desolate, and non-descript landscape. He exclaims, “How awesome is this place. This is none other than beth-el, the house of God.”

Rebecca Solnit again. She leans on Tibetan wisdom: “Emptiness is the track on which the centered person moves.” Is it possible, I wonder, that a journey precipitated by feelings of anxiety, bewilderment, and even abandonment (I imagine our forefather thought, “Now my brother wants to kill me. My father tells me to get out. Where am I to go? What am I to do?”) leads to finding one’s bearings? Jacob’s uncertain path is becoming clearer.

In Tibetan, the word for path is “shul.” Solnit continues:

[Shul is] a mark that remains after that which made it has passed by—a footprint, for example. In other contexts, shul is used to describe the scarred hollow in the ground where a house once stood, the channel worn through rock where a river runs in flood, the indentation in the grass where an animal slept last night. All of these are shul: the impression of something that used to be there. A path is a shul because it is an impression in the ground left by the regular tread of feet, which has kept it clear of obstructions and maintained it for the use of others.It seems to me that this is how we also view shul (the Yiddish term for synagogue). It is a path left by others. And now, I am left wondering.

How does our shul not become an “impression of something that used to be there”? If synagogue is only about our imaginations of yesterday, then how do we carve our own path? If authenticity is only driven by what we believe our parents, grandparents, and great grandparents did, and did not do, then how do we create our own impression, in our own image? Too much of what we expect, and want, from our synagogues revolves around the question of how they honor the past. “There is not enough Hebrew at that synagogue” is, for example, a common refrain.

I am thinking. How can we carve a path while looking backward? How do we find our way when looking back, at some impression of yesteryear? How then do we find our own shul?

It is not just a building. It is not as well a destination. It cannot only be the impression made by others, long ago.

It is instead a path.

Jacob awakes, startled, but perhaps more aware. He exclaims, “Surely the Lord is present in this place.”

Where?

Exactly where you are standing.

Just leave the door open.

And heed the voice.

Get up. Go.

Thanksgiving Poems

As we prepare to gather with family and friends in celebration of Thanksgiving and give thanks for the plentiful food, and wine, arranged before us, we pause to acknowledge the privilege and blessing of calling this country our home.

I turn to my poetry books. Recently I discovered Samuel Menashe.

Samuel Menashe was born in New York City in 1925 to Russian Jewish immigrants. He served in the United States infantry during World War II and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. After taking advantage of the GI bill, he traveled to France and earned his PhD from the Sorbonne. Later he taught poetry and literature at CW Post College. He died in 2011. He is a relatively unknown American poet.

Perhaps reading his poetry might help to remind me of how America has inspired Jews and given rise to untold Jewish creativity. His poems, at times feel playful, but then again religious.

I offer three poems:

I turn to my poetry books. Recently I discovered Samuel Menashe.

Samuel Menashe was born in New York City in 1925 to Russian Jewish immigrants. He served in the United States infantry during World War II and fought at the Battle of the Bulge. After taking advantage of the GI bill, he traveled to France and earned his PhD from the Sorbonne. Later he taught poetry and literature at CW Post College. He died in 2011. He is a relatively unknown American poet.

Perhaps reading his poetry might help to remind me of how America has inspired Jews and given rise to untold Jewish creativity. His poems, at times feel playful, but then again religious.

I offer three poems:

LeavetakingEach day is indeed a blessing. Every day is an occasion for giving thanks.

Dusk of the year

Nightfalling leaves

More than we knew

Abounded on trees

We now see through

Hallelujah

Eyes open to praise

The play of light

Upon the ceiling—

While still abed raise

The roof this morning

Rejoice as you please

Your Maker who made

This day while you slept,

Who gives you grace and ease,

Whose promise is kept.

‘Let them sing for joy upon their beds.’— Psalm 149

Now

There is never an end to loss, or hope

I give up the ghost for which I grope

Over and over again saying Amen

To all that does or does not happen—

The eternal event is now, not when.

At What Age are We Called Wise?

If we pray every day and offer the tradition’s prescribed set of prayers, we begin with the singing of psalms and the recitation of blessings. The prayer book’s philosophy is that a soul can be both fortified, and unburdened, by the shouting of blessings and praises for our God. Only then do we move on to our requests. And the very first request we make of God is the following:

Why begin our litany of requests by asking for knowledge, insight and wisdom? Knowledge is something that is gained by study and learning. Insight, which other prayer books translate as understanding, is something that is acquired after much discussion and thought. And wisdom is attained only after years and years of experience.

Perhaps we begin with these words because the rabbis who authored these prayers believed that all knowledge, insight and wisdom begin with God. I now wonder. Can a prayer really be a prayer if it does not connect the mind to the spirit? In the Judaism that I love, and teach, head and heart must be combined. There should be a unity of thought and deed. I stand against thoughtless actions.

Then again, I find that my mind often wanders during our prayers. I discover myself singing the words but thinking of the day’s events or my weekend’s plans. I sing “Adon olam asher malach…” but my thoughts turn to the morning’s bike ride (I crushed that hill) or the evening’s dinner plans (I am looking forward to the tuna sashimi).

Is the unity of thought and deed possible all the time, in every moment?

I pray again, “God, please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.”

It is a never ending struggle. It is a daily endeavor. Can knowledge, insight and wisdom be granted by God? Are they not in our hands? Perhaps this first request, this first prayer is a reminder of what I must do each and every day. Commit myself anew to the attainment of knowledge. Read something new. Of insight. Ponder the words I read again and again. But wisdom?

This cannot be achieved in a single moment, or by the performance of a solitary act. It is not acquired by carefully reading a certain book, no matter how important or holy that book might be. Even though the Torah is read again and again, and over and over, wisdom still eludes us.

Wisdom is gained only after years and years. It is the sum total of countless experiences. Can a twenty year old ever be called wise? Can a fifty year old really be imbued with wisdom?

At what age is one be deemed wise?

At seventy? At eighty three? A hundred and twenty?

We read, “Abraham was now old, advanced in years.” (Genesis 24) In Hebrew, zaken, old is associated with wisdom. The rabbis teach that zaken points to an acronym, “zeh kanah hokhmah—this one has acquired wisdom.” Old is not a measure of years but instead a sign of wisdom. Zaken does not mean aged but wise.

And how old is Abraham? 175 years.

I have acquired this knowledge. I have gained this insight. I have achieved this wisdom.

Each of us has many, many more years to go before attaining wisdom and before being called, zaken.

You grace humans with knowledge and teach mortals understanding. Graciously share with us Your wisdom, insight and knowledge. Blessed are You, Adonai, who graces us with knowledge.Before asking for health or even forgiveness, we beseech God, and say, “Please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.” This is a curious place to begin. Why is this the first of our asks? Why begin the emotional exercise of prayer with a request for the intellect?

Why begin our litany of requests by asking for knowledge, insight and wisdom? Knowledge is something that is gained by study and learning. Insight, which other prayer books translate as understanding, is something that is acquired after much discussion and thought. And wisdom is attained only after years and years of experience.

Perhaps we begin with these words because the rabbis who authored these prayers believed that all knowledge, insight and wisdom begin with God. I now wonder. Can a prayer really be a prayer if it does not connect the mind to the spirit? In the Judaism that I love, and teach, head and heart must be combined. There should be a unity of thought and deed. I stand against thoughtless actions.

Then again, I find that my mind often wanders during our prayers. I discover myself singing the words but thinking of the day’s events or my weekend’s plans. I sing “Adon olam asher malach…” but my thoughts turn to the morning’s bike ride (I crushed that hill) or the evening’s dinner plans (I am looking forward to the tuna sashimi).

Is the unity of thought and deed possible all the time, in every moment?

I pray again, “God, please grant us wisdom, insight and knowledge.”

It is a never ending struggle. It is a daily endeavor. Can knowledge, insight and wisdom be granted by God? Are they not in our hands? Perhaps this first request, this first prayer is a reminder of what I must do each and every day. Commit myself anew to the attainment of knowledge. Read something new. Of insight. Ponder the words I read again and again. But wisdom?

This cannot be achieved in a single moment, or by the performance of a solitary act. It is not acquired by carefully reading a certain book, no matter how important or holy that book might be. Even though the Torah is read again and again, and over and over, wisdom still eludes us.

Wisdom is gained only after years and years. It is the sum total of countless experiences. Can a twenty year old ever be called wise? Can a fifty year old really be imbued with wisdom?

At what age is one be deemed wise?

At seventy? At eighty three? A hundred and twenty?

We read, “Abraham was now old, advanced in years.” (Genesis 24) In Hebrew, zaken, old is associated with wisdom. The rabbis teach that zaken points to an acronym, “zeh kanah hokhmah—this one has acquired wisdom.” Old is not a measure of years but instead a sign of wisdom. Zaken does not mean aged but wise.

And how old is Abraham? 175 years.

I have acquired this knowledge. I have gained this insight. I have achieved this wisdom.

Each of us has many, many more years to go before attaining wisdom and before being called, zaken.

No Retreat from the World

I retreat to the Torah. It is a welcome distraction from the news and our country’s painful divisions.

This week we read about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. These cities are marked by sinfulness. As in the story of Noah, God decides to start all over and wipe out the sinfulness. Again God shares the plan with a chosen, and trusted, person. This time it is Abraham. God says, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do?” (Genesis 18)

God reveals the plan to Abraham. But Abraham pleads in behalf of the people. Abraham argues (and negotiates) with God exacting a promise that if ten righteous people can be found then the cities should be saved. In the end Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed. By the way, some suggest is the origin of the required number of ten for a minyan.

And yet the Torah is unclear about what these cities’ inhabitants did that was so terrible. What were their sins? We are given only hints. “The outrage of Sodom and Gomorrah is so great, and their sin so grave!” Throughout the ages commentators have suggested that the people were guilty of sexual depravity. They cite as evidence the accompanying story that the townspeople attempted to rape the divine messengers who visit Lot, a resident of Sodom and a nephew of Abraham. This explains the English term “sodomy.”

Later the prophet Ezekiel offers more detail: “Only this was the sin of your sister city Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility; yet she did not support the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16) He sees their sin in social terms. The cities were destroyed because of their failure to reach out to the needy and most vulnerable. There was plenty of food to share and yet they kept it all to themselves.

They were arrogant. They felt themselves superior. They shared little with the hungry. They turned a blind eye to those in need.

The rabbis expand upon the prophet Ezekiel’s understanding. They saw the cities’ sinfulness in their treatment of others, most especially their failure to fulfill the mitzvah of hospitality and welcoming the stranger. They argue that this sin would have been understandable if Sodom and Gomorrah were poor cities, but they were in fact wealthy. The rabbis weave a story describing the streets of these cities as paved with gold. They taught that the cities’ inhabitants flooded the cities’ gates in an effort to prevent strangers from entering and finding refuge there.

In the rabbinic imagination, the cities were destroyed because of their own moral lapses. They were affluent. There was plenty of food for them to eat. Yet they did not share it with anyone. They hoarded it for themselves. They prevented strangers from entering their cities. They thought only of their own welfare and their own livelihood.

I hear Rabbi Gunther Plaut teaching, “The treatment accorded newcomers and strangers was then and may always be considered a touchstone of a community’s moral condition.”

And I am left to wonder. Can any retreat be found?

I search in vain for distractions.

The Torah appears to speak of today. It continues to speak to today.

That is its most important, and powerful, voice.

Perhaps I should give up the search…for distractions.

This week we read about the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. These cities are marked by sinfulness. As in the story of Noah, God decides to start all over and wipe out the sinfulness. Again God shares the plan with a chosen, and trusted, person. This time it is Abraham. God says, “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do?” (Genesis 18)

God reveals the plan to Abraham. But Abraham pleads in behalf of the people. Abraham argues (and negotiates) with God exacting a promise that if ten righteous people can be found then the cities should be saved. In the end Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed. By the way, some suggest is the origin of the required number of ten for a minyan.

And yet the Torah is unclear about what these cities’ inhabitants did that was so terrible. What were their sins? We are given only hints. “The outrage of Sodom and Gomorrah is so great, and their sin so grave!” Throughout the ages commentators have suggested that the people were guilty of sexual depravity. They cite as evidence the accompanying story that the townspeople attempted to rape the divine messengers who visit Lot, a resident of Sodom and a nephew of Abraham. This explains the English term “sodomy.”

Later the prophet Ezekiel offers more detail: “Only this was the sin of your sister city Sodom: arrogance! She and her daughters had plenty of bread and untroubled tranquility; yet she did not support the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16) He sees their sin in social terms. The cities were destroyed because of their failure to reach out to the needy and most vulnerable. There was plenty of food to share and yet they kept it all to themselves.

They were arrogant. They felt themselves superior. They shared little with the hungry. They turned a blind eye to those in need.

The rabbis expand upon the prophet Ezekiel’s understanding. They saw the cities’ sinfulness in their treatment of others, most especially their failure to fulfill the mitzvah of hospitality and welcoming the stranger. They argue that this sin would have been understandable if Sodom and Gomorrah were poor cities, but they were in fact wealthy. The rabbis weave a story describing the streets of these cities as paved with gold. They taught that the cities’ inhabitants flooded the cities’ gates in an effort to prevent strangers from entering and finding refuge there.

In the rabbinic imagination, the cities were destroyed because of their own moral lapses. They were affluent. There was plenty of food for them to eat. Yet they did not share it with anyone. They hoarded it for themselves. They prevented strangers from entering their cities. They thought only of their own welfare and their own livelihood.

I hear Rabbi Gunther Plaut teaching, “The treatment accorded newcomers and strangers was then and may always be considered a touchstone of a community’s moral condition.”

And I am left to wonder. Can any retreat be found?

I search in vain for distractions.

The Torah appears to speak of today. It continues to speak to today.

That is its most important, and powerful, voice.

Perhaps I should give up the search…for distractions.

Two States for Two Peoples

Last week I attended JStreet’s National Conference in Washington DC. What follows are some of my impressions. First a word about JStreet’s mission. JStreet was founded a little over ten years ago to advocate for, and lobby in behalf of, a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In other words, it supports the creation of a Palestinian state in a large portion of the West Bank, as well as perhaps Gaza, living alongside the Jewish State of Israel. AIPAC by contrast, although officially affirming the need for two states, avoids prescribing a solution to this conflict, claiming instead that this is for Israelis, and Palestinians, to decide. AIPAC’s mission is to make sure there is strong bipartisan support for Israel, and in particular for Israel’s security, in the United States Congress.

I will also be attending the AIPAC Policy Conference the beginning of March. Unlike AIPAC which both Democrats and Republicans attend, there were only senators and representatives from the Democratic Party at JStreet. There were also only Israelis from the center and left in attendance. While I recognize that many find JStreet controversial I struggle to understand why it is deemed out of bounds. Among those in attendance, and those who spoke to the 4,000 participants, were Ehud Barak, former Prime Minister and Israel Defense Forces chief of staff, and Ami Ayalon, former director of Shin Bet (Israel’s internal security service) and admiral in Israel’s navy. Their security credentials are unmatched. More about that later. First a few details about my personal journey regarding the question of two states for two peoples.