Get Angry, Be Joyful

The spiritual quest is not about finding a new forest, or even a different and safer forest, but instead about finding a new self. It is about changing ourselves. Every day we are different. And every day we have to start that search anew. The search is about making ourselves different, each and every day. And that to be honest, is confounding and exceedingly difficult, most especially given the times we currently find ourselves in. How do we get up each morning and go out into the world, when confronted with such uncertainty? Every day there seems some new bit of evidence, or advice, about when to wear masks or how many shots to get. Is it advisable to go out to a restaurant, or Yom Kippur services? Is it ok to get together with friends now that the Delta variant is circulating? Is the forest safe or dangerous? Last night we tackled the question of how do we live through change. And the answer was—or to be fair my answer was, embrace it. Make it your own. This morning’s question is more personal. How do we deal with uncertainty? How do we continue to wrap our arms around life when faced with uncertainty after uncertainty after uncertainty? And the answer is. By changing ourselves.

The problems, and challenges, of the past year are here to stay. We naively believed that this High Holidays would be the same as 2019 and that 2020 would be just a blip. We thought this year would offer us the opportunity to reflect on what we learned during the pandemic not that we would still be in the midst of it. Let’s be honest. We will be living with Covid for the foreseeable future. We have two choices. Pretend like it’s no big deal and will go away soon or face the painful truth that our present reality is going to be part of our lives in some way for years to come. We will be wearing masks for far longer than we ever imagined possible. We will be monitoring infection rates for years to come. And this acknowledgment that the end is not yet in sight creates tremendous uncertainty and unease.

Of course, we would all prefer that our lives could go back to those days when we did not wonder whether or not the person we brushed up against is vaccinated or not, whether talking to an unmasked stranger in the supermarket line is dangerous or not. The only way to deal with such unpleasant realities is to acknowledge them. The only way to tackle our fears is to own them. Head into the forest. Not to escape the world but to discover a new you. We can change the world a little bit, but we can change ourselves a lot.

First let’s talk about how we change the world. There are so many problems our world is facing. I am sure each of us has a lengthy list. I explored a number of these contemporary challenges on Rosh Hashanah. My question on this Yom Kippur is not so much what these problems are, but how we can face them. Here is the surprising answer. Get angry. Ignite action. You might be surprised to hear me say this. I think we need to discover the right kind of anger. We need to recover the sense that we can change things, that our seemingly insignificant actions can write a new course for the world. We are not allowed to say, “It does not matter what I do.”

We must reclaim the passion of the prophets of old, who so felt the urgency of the problems in their own day that they sacrificed almost everything else in order that others might take up God’s call. This morning we chanted the words of Isaiah. He said: “Is not this the fast I desire—to break the bonds of injustice and remove the heavy yoke; to let the oppressed go free and release all those enslaved? Is it not share your bread with the hungry and to take the homeless poor into your home, and never to neglect your own flesh and blood?” (Isaiah 58) I admit. Their passion and righteous indignation often got the better of them. They frequently pushed family and friends away. They were consumed by God’s message. They were overwhelmed by their anger. They always shouted. And never listened. Abraham Joshua Heschel remarked, “The prophet is human, yet he employs notes one octave too high for our ears.” (The Prophets)

The brilliance of our rabbis was to take the prophets’ words out of their own times and place them as weekly, contemporary reminders. They have us read these words of the Haftarah at the exact moment when we might be thinking, “Wow, even though I am really hungry, this hunger is my path to holiness.” No. This Yom Kippur fast is not enough. And it is not even the main thing. It is so we understand what hunger means. It is so we think of those who do not have enough food to feed their families. It is so we think not of the bagels and lox waiting for us after a long day of prayer and repentance but instead of those who are hungry and homeless only miles from our homes. It is a shame that we too often chant the prophets in Hebrew rather than dwell on the meaning of their words. The Hebrew insulates us from their all too contemporary message. We need to rediscover their passion. We need to reclaim a measure of the prophets’ anger.

David Whyte offers this counsel: “Anger is the deepest form of compassion, for another, for the world, for the self, for a life, for the body, for a family and for all our ideals, all vulnerable and all, possibly about to be hurt…. Anger is the purest form of care, the internal living flame of anger always illuminates what we belong to, what we wish to protect and what we are willing to hazard ourselves for.” (Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words) Whyte points us towards a truth we must reclaim. Anger is about becoming attuned to the world’s hurt and allowing it to make us do more than just curl up in bed and cry. It is about lighting a fire so that we get up each and every day and get out there and start fixing things—or at the very least start trying to change things in our own little world. We are not allowed to look at the world and shrug. We are not allowed to become exasperated and lose hope. And while we cannot hold all the world’s problems in one heart, we each have the strength to hold a few.

Start somewhere. Start fixing something. Get out there and do something about all this mess. There is plenty of brokenness to be repaired. That begins with the emotion of anger. Of course, we cannot, and should not, stay angry all the time. Too often we confuse anger with rage. That is what we keep getting wrong. Anger is about concern. It begins with justice and a feeling about what must be righted. It is about believing that this or that must be improved and can be made better. Rage is about pointing fingers and assigning blame. It is about shouting at others, whether that be politicians or even friends. Rage leads to measuring success against the missteps of political opponents and our ideological foes. Too often rage takes us down a path of vengeance. Anger comes from a soul that believes the world can be made better, the world is deserving of repair. It begins with concern for others and the world. It stems from a belief that this crumbling earth is deserving of our blessings and our efforts to improve it. Anger is about channeling the chutzpah of the prophets and saying, “I may very well be the person who can bring some healing.” That is why we welcome the prophet Elijah to every baby naming. We say, “This kid might really fix things.” Rage begins with the clenched fist. Anger emerges within the heart. Anger leads us to bringing a measure of certainty to all this uncertainty.

The other way involves some shouting too. Instead of shouting our passionate anger, we shout joy at this uncertainty. We sing for joy even though life is so maddeningly random. Again, there is confusion. We think control offers certainty. (Haaretz, September 10, 2021) We think that if we shout louder, bring more fervor to our songs, or recite our prayers perfectly at their exact appointed hour, then our fate will be better sealed. Decisiveness about our prayers does not change the randomness of life. There is much beyond the reach of our hands. There is much beyond the influence of our prayers. Look at the frightening Unetanah Tokef prayer we chanted. “On Rosh Hashanah this is written and on the Fast of Yom Kippur this is sealed: How many will pass away from this world, how many will be born into it; who will live and who will die; who will reach the ripeness of age; who will be taken before their time; who by fire and who by water…” And what is this prayer about? It is about affirming the haphazard, and randomness, of life. The back-and-forthness of its list gives voice to life’s uncertainty.

People might be saying, “I want more certainty. I want my rabbi to tell me if I pray this prayer better then everything will be ok.” I will not. I will not offer fantasies. Such guarantees are an illusion. Go elsewhere if you want magic. I can only offer healing. I can promise that singing will dispel some of that fear. I can offer the assurance that our prayers can help us push some of that uncertainty into a corner of our hearts and help to keep it tucked away there. All we can do is sing. All we should do is sing. I know this is an imperfect answer. Then again life is an imperfect journey. There is so much to fear. How are we going to conquer it? That is an impossible quest. There is only one possibility. Figure out where you can hold these fears and how you can more than occasionally cast them aside.

As many people now know, I was in a bike accident five weeks ago. As you can see, I am ok, and although my ribs and shoulder are still bruised, I will be back on the bike as soon as the replacement parts arrive, and it can be repaired. Here is the story of what happened. I was finishing a quick 25-mile ride and was at the 20-mile mark when I decided to add a hill and then loop back to my house by way of Huntington harbor. This new route involved going on more heavily trafficked road. I was rounding a bend when all of sudden I saw black in front of me. I quickly realized this was the side of a car, pulling out from the auto body shop of all places, and so I squeezed the brakes. My rear tire slid sideways, and I heard a terrible crunch as my right side slammed into the car. The next thing I know I am lying on the pavement, writhing in pain, while people are screaming, “Someone call 9-11. I can’t get a signal. Can anyone get a signal?” And I remember thinking, “Of course you can’t a signal. This is Long Island.” And then I thought, “All this screaming and shouting, ‘Call 9-11’ is about me.” Then I had the most frightening thought, “That’s a really good idea.”

Someone else kept shouting, “Hey buddy. Don’t move.” And another screamed, “Is there someone I should call?” I said, “Call Susie. Her number is on my ankle bracelet.” John called Susie but she did not pick up. Everyone was screaming. I guess the good kind of shouting really does come from the heart. Bill put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Don’t move. The EMT’s are on their way. You’re going to be alright.” The ambulance arrived and they loaded me on to a stretcher. They then gave me my phone and I called Susie. She answered and I said, “Hi sweetheart. I’m ok, but I was in an accident, and they are taking me to the hospital.” And then I added words that would only be heard in a rabbi’s house, “You should go do your congregant’s funeral first and then meet me at Huntington Hospital after you’re finished.” “Are you sure?” she asked. “I am coming now” she shouted. “No,” I insisted. “I am going to be ok. I love you. See you soon.” Two hours later, as well as after an IV and some CAT scans, I walked out of the hospital. No broken bones. No head or neck trauma. No internal injuries. To say I am really, really lucky is an enormous understatement.

I keep thinking if I was going a little faster, he would have slammed into me and sent me flying over the car’s hood and perhaps into oncoming traffic. If he was delayed ten seconds I would have whizzed right by and would never have come to know his name. Those differences can be measured in seconds and inches. Well-meaning friends kept saying, “God was watching out for you.” And I also keep thinking, “What if? Why me? What about others who are not so lucky? And I have a list of those names carved into my soul. I have been doing this rabbi thing for a long time—thirty years to be exact—and all I can say for sure is there is no such thing as a protective bubble. And I don’t know why. I have no perfect answers to all this randomness and uncertainty. And I don’t believe anyone who offers them. I am hesitant before certitudes.

This does not mean I should stop wearing a helmet. A new one is already waiting for me. Just because life is random and there are no guarantees does not mean we should take unnecessary risks and not take precautions. To any of my students who decide to ride a bike without wearing a helmet, I promise you this. You will have your rabbi to answer to in addition to your parents. And on another more important note, get the vaccine. Wear a mask in crowds. Prayer is no substitute for common sense and good medicine.

The Unetanah Tokef prayer affirms life’s randomness. I admit this is disquieting. We crave certainty. And still we sing its words with joy. We offer this upbeat tune that belies the prayer’s frightening imagery. And that tune is the truer word. The song exemplifies our best response. That energetic, and lively, way we sing Unetanah Tokef summarizes how we should approach all this randomness and uncertainty. “B’rosh Hashanah…” The secret is the song. Prayer is not really about theology. It is instead about the music. Only that can fill the cracks in our hearts. Only the song can placate our fears.

When I lie awake at night, I can still hear the crunch as my body smashed into that car. I also can still feel the hand of a stranger on my shoulder. I can still hear his words, “You are going to be alright.” And I can also still feel my grandfather’s hand on my back when I first learned how to ride a bike. I can still hear his voice from fifty some years ago, “You’re doing it Steven. No more training wheels. You’re riding a bike.” These feelings will get me back on the road. His shouts of joy behind me carry me forward. Our tradition’s songs pacify my fears.

There is a road forward. It is carved by finding a new self. It is paved with two emotions. Be joyful. Get angry. That is the path to a new self. That is the road forward.

Get angry. And ignite action. Be joyful. And spark happiness. These must be our twin responses to all this uncertainty. Hold both of these together. Hold both of these at once.

Embracing Change

Let me tell you about our people’s survival. It is captured by a story from nearly 2,000 years ago. It involves the events surrounding the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E, the most catastrophic event the Jewish people ever experienced, until the twentieth century’s Holocaust. It is the story about Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai. During the siege of Jerusalem by the Romans, Yohanan was secreted out of town by his students. They carried him to the Roman general’s camp in a coffin. There he negotiated with Vespasian that Yavneh be spared so that a rabbinic academy could be established there.

Why did he need to sneak out of Jerusalem? Because his Jewish compatriots might very well have killed him. So divided were the Jewish people during those years that he feared for his life. He was a known critic of the Sadducees who stubbornly held fast to the rituals surrounding animal sacrifices. Yohanan ben Zakkai also stood against the Zealots who took up arms against the mighty Roman army. He argued that making peace was the best course of action, that accommodation with forces more powerful than our own would best ensure our survival. That is the story in a nutshell. That is also not how we tell it.

Instead, we never even visit Yavneh. On every trip to Israel, the tour guide wakes us up early in the morning so we can climb the winding snake path to Masada’s fortress. There we watch the most glorious sunrise over the mountains. The sight never fails to take my breath away.

There we glorify the events surrounding Masada’s downfall. We tell the story of how the Zealots held out for three years following the destruction of Jerusalem. When our heroes realized that the Romans would soon break through the fortress walls, because they had completed a ramp on the mountain’s opposite side, the Zealots decided to commit mass suicide rather than be taken as slaves. The Roman army arrived to find the food stores full, but all the Jews dead, save one, or perhaps two, who would tell this tale so that future generations would know it. And we continue to hail our ancestors’ heroism. We sing accolades to their bravery.

Most people know the story of Masada. Few know that of Yavneh. Masada might be more majestic, it might be more thrilling, but Yavneh is why we are still here. It is why we continue to offer our Yom Kippur prayers. We prefer to glamorize the defeated warriors. We push to the footnotes of history the compromisers. We fail to admit one generation’s traitor is history’s savior.

We persist in telling the story that glorifies martyrdom. We prefer to round out those jagged historical edges removing the fact we were so divided we wanted to kill each other. We tend to minimize the arguments and disagreements, the divisions and civil wars, the partisanship and vitriol of yesterday in favor of telling tales in which there are clear villains and heroes, even if those heroes died by their own hands. But history can only be told by those who choose life. And that path involves complicated choices, and compromises. Often, what appears radical to contemporaries, history records as decisive. What his fellow Jews saw as making a deal with evil doers, what the Zealots saw as unacceptable changes and compromises, history judges as crucial to our survival.

The Sadducees refused to change. Their system was destroyed. The Zealots fought against everyone and anyone who suggested compromise. They died. Here is a promise and prediction. The future will not look like the past. And here is the more important point. The future must not look like the past. I know. This is not a particularly revelatory observation. But if we recognize this, why do we act as if we want the future to look like the past? History suggests, or at least how history actually went down rather than how we memorialize it, that we have only one choice. Embrace the future with all its uncomfortable compromises and sometimes painful changes. Do you think Yohanan ben Zakkai thought the Roman general Vespasian was a great guy? Do you think he really wanted to sit down with this terrible man and ask him for that meager morsel of Yavneh? But that is why we are still here.

Recently I woke up from a nightmare. Here is the picture my subconscious painted. I walked into our beautiful new sanctuary and looked up at the back wall to discover that the Livestream camera had been removed. I panicked because I realized that few people would be able to join us for Shabbat services. No one would be able to sing Lecha Dodi with our cantor. No one would be able to recite the Kaddish when they joined us from Los Angeles. We don’t need to spend too much time trying to figure out part of the meaning behind this dream. I was obviously stressed out about simultaneously leading services and making sure all the tech works. But the other, and more important, piece deserves further interpretation.

More people are joining us online than are present here in the sanctuary in person. “Don’t say that out loud rabbi,” some might be saying, but when have I ever shied away from shouting the truth? Part of the reason why this is true is because of this maddening, and seemingly never ending, pandemic. But the other reason is that it is easier to join services from home than to come in person. Is it as good as being here in person? I would like to think not. Is a Broadway show better in person or on TV? When here, I would argue, it is easier to leave the world behind. Here, it is easier to connect with others. Here the distractions of home and work can be pushed aside at least for a brief hour.

Is it possible to find meaning and celebrate Shabbat or these High Holidays online? Absolutely. Let’s be honest. You can dress more casually. You can watch while you are still eating your dinner. You can relax on your comfortable, and well cushioned, couches. You can also join services at whatever time is most convenient for you. Watch Friday night services on Saturday afternoon if you like. You can fast forward through my sermon or even watch last week’s lengthy sermon at 2x speed if you like. (20 minutes become 10 minutes!) You can sit with your children and only join us for the Shema and V’Ahavta. All these are possibilities. Is this a nightmare or a dream? That choice is ours to make. And the choice seems clear. Our survival depends on being amenable to change and open to adapting to new circumstances and different realities. We must never be about saying, “It’s only good if you are here with me. It’s only good if you do what I do.” We must instead be about bringing meaning and spirituality far beyond these walls. We must be more like Yohanan ben Zakkai.

I know it's uncomfortable. I get it. Change is the stuff of nightmares. Then again change also guarantees our survival. It is the stuff of future dreams. For some these renovations, and modernizations, to our new sanctuary are unnerving. I get that it is hard, and uncomfortable, to come to the place you called home and see it changed. I get that change is hard most especially in this place. Here people want to feel the comfort of the past. But the past is imagined differently by each and every one of us. We tell it the way we want to hear it. We tell it the way we wish to glorify it. Look at how we tell the story of the Zealots rather than the more crucial tale of Yohanan ben Zakkai and his followers. We herald those who resisted change and sacrificed themselves, rather than emulating those who made the uncomfortable, but necessary, changes that guaranteed our survival. In truth, change is part of our Jewish DNA.

For the past year and a half, there has been a regular shiva minyan in my home. Either it was on Susie’s computer and for her congregation or on mine and for our congregation. My friend, Jamie Reiss z”l, who died this past year thought all this online stuff was not a good substitute for the real thing. It is an understatement to say he was a people person. And yet when he died in February, we had no choice but to gather on Zoom for shiva. And again, Zoom provided something that in person shiva could not have offered. There on my laptop was visual evidence of how many people were also touched by this loss. I was comforted by their faces. I scrolled through page after page after page. I was uplifted to see their tears up close. I noticed that people joined us from far away states and even countries.

Often, after concluding the minyan service for these Zoom shivas, I would turn off my video, but keep the audio on in case I was needed for tech support. And I would hear the most wonderful stories. I began to realize that Zoom seemed to make shiva more about the person who died. All those conversations about traffic and the weather were no longer relevant. Good riddance! Could I wrap my arms around the mourners? No. Did Zoom provide something else? Yes. More people heard these beautiful stories. More people shared touching memories. Is this change here to stay? Absolutely. Embrace it.

And yet we still teach our children as if Jewish education is about anything but change. We speak as if survival is about doing Judaism exactly as our great-grandparents did rather than taking the tradition and molding it into something different for the 21st century. We pretend our Hebrew Schools are about fashioning 21st century Jews when in truth they are too much about telling them what we want them to believe. Ask yourself these questions. Do we really want our children to think for themselves? Do we want them to look at this wonderful inheritance differently or just be perfect imitations of ourselves? Do we truly believe in education, or do we want indoctrination? I believe education must be about teaching children how to interpret their lives for themselves. It is not about parroting parent’s views and ideas but instead about forming their own notions and creating new Jewish paths. Sure, I sometimes don’t agree with every choice, but rather than judging our children’s decisions we might be better off by saying this. “I have faith in you. Learn. Make your own way.”

This tension between what true education should look like is no where more pronounced than when we talk about Israel. Let me lay out the conflict and it saddens me to say this out loud. Our youth are turning away from Israel. They no longer love Israel as prior generations of Jews did. I believe, however, we should be blaming ourselves for this problem rather than our children. When it comes to Israel, Jewish educators only want to tell the history as they imagine it, the story as it resonates in their own hearts. We only want to speak of the Israel we love and hold dear. We become crazed when our children question why we feel more attached to the suffering of Israelis than that of Palestinians. We become outraged when they say things like, “I agree with Ben & Jerry’s decision.”

But if they are going to love Israel, their love is going to look different than ours. They might not love it as much as I do. And we are going to have to figure out how to say, “I wish you felt differently but I understand. Your Jewish path is going to be different than my own.” And then we should add, “Promise me this. Go to Israel. Talk to Israelis. Become familiar with the diversity of opinion among them. And then figure out your path.” No amount of shouting is going to foster love. Now amount of saying, “What’s wrong with you?” is going to compel attachment. I am not interested in indoctrination. I believe in education.

And education is not about raising the volume of our voices, and shouting louder, when we fail to convince others of what we believe to be the correctness of our own opinions. It is not about saying, “If only these kids knew what I know or experienced what I experienced, then they would see what I see.” It is instead about presenting the facts and issues and then saying, “Let’s discuss and debate. Let’s ask, ‘What do you think?’ No opinion is off the table. No feeling is out bounds.” Of course, there is a Jewish point of view. Of course, there is my opinion. (In case you have not figured this out already, I am really opinionated.) Let’s be honest. The traditional view might not end up being my children’s view. Have more faith in them and their decision making than in agreement. Have more faith in them and the moral compass you give them than in conformity. Have faith that they can find a new way rather than the worn path of experts and elders. They are going to change things. Believe in them.

They will weave their own tapestry in the words of Torah. The Jewish tradition is not one that believes God’s words begin and end with the verses of Torah. It assumes that we take those words and interpret them and then reinterpret them for our own age and our own time.

We make them new, and current, through interpretation. In fact, the greatest praise that one can offer a darshan, a sermon giver are the words, “That was a beautiful hiddush.” In other words, that was a beautiful, novel interpretation. We praise seeing something new in these ancient words. We do not praise regurgitating old words. We make them new, again and again, with our own minds. Akiva and Rashi might very well have been greater masters, but their lives are not our lives. Each of us must interpret the Torah anew.

It is not going to be like yesterday. The future is going to be far different than the past. We have only one choice. Embrace change. Why? Because that, and that alone, will save us.

Think about a Jewish wedding and the concluding ritual of breaking a glass. It signifies that the couple are now officially married and that the dancing can begin. This custom began in Talmudic times. According to the Talmud’s own telling, Rav Ashi (or was it Mar son of Ravina) was throwing a wedding feast for his son. Apparently, some of his guests, and some of the other rabbis, were having too good of time (perhaps they had too much tequila) and were becoming quite boisterous. So, the host broke a glass to quiet them down. He reasoned that their joy should be tempered given that Jerusalem’s holy Temple was destroyed. And here is what is often forgotten. Rav Ashi lived in Babylonia, almost 300 years after Jerusalem was leveled by the Romans.

And he was still thinking about those tragic events. Now he did not say, “We must not dance.” Instead, he said, “Celebrate the present. Remember the past.” Even at this happiest of occasions, we pause to remember the past. Still, we are not bound by it. We are not encumbered by it.

How do we do recall the past that while embracing the future? That is the central question for the 21st century synagogue. The very same question Yohanan ben Zakkai faced is the question we now face. We have no choice but to embrace this essential truth. The future will not look like the past. The future must not look like the past. Nothing is going to be like it was before. And yet there will always remain imprints. There will always remain shards of broken glass that help to carry us forward.

And finally, a wish and a prayer. When we buy something, a new car or a new house, a new iPhone or even a new bike, we do not say, “Mazel tov,” but instead “Titchadeish.” Mazel tov means something is completed. Titchadeish means something new has begun. We say, “May you be renewed by this.” May you find something new, may discover some new teaching, some new meaning, some new revelation in this simplest of objects. May this thing add new meaning to your life. And so, we shout, may this renewed sanctuary grant our congregation new life. May it offer us new revelations.

I guarantee you this. We are going to be changed. I also guarantee you this. We are going to survive.

Zoom Stories

This was not the shiva I had come to know in my thirty years of being called rabbi. In the past this is what I instead observed. More often than not people would arrive and find their way to the kitchen. They would exchange sometimes uncomfortable “Hello’s” and “It’s so sad.” They would talk about the weather’s latest storm or the maddening traffic, or a confounding Jets loss or on occasion, a surprising Mets win.

There were times when I would observe a beautiful moment of healing. A familiar face to the mourner, but a stranger to me, would come over and say, “Can I tell you about when your dad did this for me?” or “Can I tell you a story about your mom? There was the time…” And that was my cue. I would offer a hug and a goodbye to the mourner because I then knew they were in good hands. I had confidence that such stories would uplift their spirits and maybe even fill their emptied hearts.

I never heard those extra stories. They seemed private utterances, between mourner and storyteller, between the bereaved and their comforter.

In this past year, however, I discovered something new. I had to stay in that virtual room because I was now managing the technology. I had to make sure Aunt You Know Who stayed muted when she loudly whispered something to her husband about a relative they had not seen in years. When I heard, “He looks like he put on some…” I quickly hit mute. And yet this year, there I was, sitting quietly in the corner as it were, listening to what would have been in past years private conversations.

Here is what I discovered. No one talked about the weather or traffic anymore. No one berated the Jets or the Mets, even though they were deserving of such chastisements. Those matters were now as they should be, inconsequential. No one had to drive through the snow or the rain to get to shiva. No one bewailed our New York sports teams because they felt they only had a few minutes to offer their words.

I heard the most beautiful stories. One time I sat there, alone in my study, and heard how a conductor on the Long Island Railroad became friends with the father who one of our members was no mourning. He said, “We struck up a conversation years ago because he was always on my train. A friendship began because of a chance encounter. My life is better for it. I am going to miss him.” I heard piles of such memories.

I felt like an interloper, and I also felt blessed, as I listened in on these private remembrances, as these stories piled up on my computer screen. I learned so much about those we lost. This year the memories of those we lost were given new life. Their stories were more easily told.

Was it because Zoom somehow created a safe distance from which to tell these tales? I do not know for sure. I know this. We are better for it. We are better because of these newfound intimacies of sharing. Perhaps we have rediscovered, during this most awful of years, the power of telling stories. Perhaps we have relearned how to bring healing to our grieving friends. Perhaps we have been reminded that community is uplifted by such memories and the retelling of them.

I know this for certain. We are better that more people learned about our mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, wives and husbands, daughters and sons. We are uplifted by the secrets we discovered on our computer screens. Perhaps they should never have remained secrets and private utterances. I feel blessed that this strange year of Zoom has unlocked these stories and granted them the life they deserve. We are blessed when we learn, once again, the power of telling our stories.

Grief is Like the Ocean

(Why We Swim)

Grief is like the ocean. There are days when the waves come crashing down upon us. There are other days when the water appears calm but then an unexpected wave knocks us off our feet and holds us down as it crashes overhead. We struggle to the surface and gasp for air. And then there are days when the waters are tranquil, and we can float on its gentle current and be carried by a sea of pleasant memories.

Grief is like the ocean. No day is the same. We have no choice but to go out and swim into the waters. We have no choice but to recount our tale.

On Yom Kippur, Lift Our Chair

In 1808, in the days before Rosh Hashanah the butcher of Teplik Ukraine made this gift for the rebbe. The rabbi was so impressed with the craftsmanship, and most especially with the fact the butcher spent so much of his free time during the prior six months making it, that Rebbe Nachman loved to sit in the chair. He felt that the kavvanah, intention, of the butcher helped to lift his prayers.

After the great rabbi’s death, this chair became a symbol of the Breslover Hasidim. How it found its way to Jerusalem is the stuff of legends. There are two stories.

The first is most likely closer to the truth. During the Cossack pogroms of the 1920’s, Rabbi Tzvi Aryeh Lippel cut the chair into pieces in order to carry it to safety. He walked, and some say ran, twenty miles to the nearby town of Kremenchug where it was then hidden by the Rosenfeld family. In 1936 Rabbi Moshe Ber Rosenfeld brought the chair to Jerusalem. It was restored in the late 1950’s by artisans from the Israel Museum, and then again in the 1980’s. The chair was then placed in the synagogue where it can be seen to this day.

The second is the story I prefer to tell. When the Nazis invaded the Ukraine, Rebbe Nachman’s disciples realized that the only way for some of them to survive was to run and to scatter throughout the world. But what should they do with the Rebbe’s chair? And so, they decided to cut the chair into small pieces and every disciple would carry a piece of the chair, and the intention of their great rabbi, as they ran for their lives.

After the war, the Rebbe’s many disciples and their descendants found each other in Jerusalem. Miraculously every single one who carried a piece of the sacred chair survived the war. In Jerusalem, they painstakingly reassembled the chair. It looked just as beautiful and majestic as the day it was made and presented Rebbe Nachman. Was that their belief or reality? Does that matter? They felt their Rebbe’s prayers in the reassembled chair.

Likewise, each of us carries a piece of our sacred tradition. And only when we are together—and these days I would add whether that be virtually or in person—can we assemble the songs of our tradition. Only when we are together can we lift our prayers on high.

Find that piece you wish to carry. Hold on to it. Assemble it together. Our survival depends on it.

Rebbe Nachman teaches: “The most direct means for attaching ourselves to God from this material world is through music and song.”

On this Yom Kippur let us assemble this chair and lift it together.

A 9-11 Prayer

The country too was empty of words that could fill the void, that could comfort us in our horror, that could assuage the first responders’ hurt. Sure, we offered memorial services, we shared songs and poems and even prayers—as if those could somehow fill the emptiness the families who lost mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, sons and daughters, husbands and wives now felt, as if those could soften the terror we also felt now that our city no longer gleamed with its chaotic enthusiasm. Our city was emptied of its hustle and bustle save the hurried, and harried, work begun at ground zero to remove the mountains of rubble. “We must rebuild,” we shouted. And we did. “We must go after those responsible for these murders,” we cried. And we did. “We must dedicate a memorial to those lost.” Again, we did.

Mostly I remember the sky. Its vastness, its blueness, its emptiness pointed to something greater. We were empty of divisions. We were unified for a brief moment in time.

That same sky will reappear tomorrow morning on September 11, 2021. We will look up to the heavens. The planes return overhead. I no longer have to strain to hear the birds sing. We will remember the sky’s royalty. Its blue thread held us together. Now that has frayed. The divisions, and recriminations, drown out the songs. The heaven’s beauty is shrouded in grey. All we hear is blame. All we see are the pointing of fingers. That is all that fills the emptiness remaining. Fear dominates our hearts. We look at our fellow Americans and see only friend or foe. Terror captivates our thoughts. Democrats blame Republicans. Republicans blame Democrats.

We have been emptied of our solidarity. Camaraderie is cast aside.

Dear God, we pray. Offer us the strength to rebuild not just our buildings, but our nation’s common purpose. Let that regal sky blue fill our hearts so that disagreement and differences no longer become divisions.

The Torah reminds us: “Fear not. Do not be dismayed.” (Deuteronomy 31)

If we are to honor the memory of 9-11, and all those we lost, let this emptiness be dispelled. Let kinship be our abiding blessing. Let unity be our future.

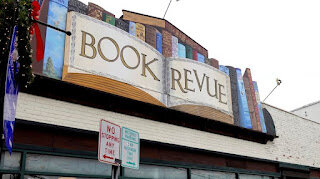

The Book (Revue) Never Closes

Tomorrow evening Huntington’s Book Revue will close its doors. Even before we moved to Huntington, we would pilgrimage there in search of books. I don’t know all the details about why it is closing. There has been plenty of online debates, and accusations, about how this was allowed to occur. I do know this. It saddens me. It is one more sadness piled on to a year of sadness.

There were countless evening outings when we would end up in Book Revue. Often, after finishing dinner at a neighborhood restaurant, we would walk around town. Inevitably we would find our way to the Book Revue. There we would often divide up and each go to our favorite sections. I usually ended up in the poetry section to see what new book had arrived. Or that destination might be chosen because Susie would say, “There is this book I want to get, let’s go see if it’s at Book Revue.” And there we would go, with friends or children in tow.

Or she might say, “I ordered something at Book Revue, let’s go pick it up.” Again, I would wander to the poetry section. I would flip through Denise Levertov, Maya Angelou, Billy Collins and Rainer Maria Rilke. On other occasions, I would lug home W.B. Yeats, Pablo Neruda, Czeslaw Milosz and Harold Bloom. It’s been eighteen years since we moved to Huntington.

I rarely if ever entered the store’s doors intending to buy another poetry book, yet the discoveries now line my shelves.

Other times we would go there with Shira and Ari. Each of us would find a corner of books to discover. Many times, we spent half of our time searching for each other trying to guess which corner Ari was exploring or which books Shira was now prying open. Inevitably Shira would find me among the poetry books (my location was predictable) and say, “I can’t find Eema and Ari.” And then we would search the bookstore together.

In which books would our family find each other?

Mary Oliver writes (there are a pile of her books from my years of travel):

I was sad all day, and why not. There I was, books piledThe Torah nears its conclusion. Moses admonishes the people: “Fear not. Do not be dismayed.” (Deuteronomy 31)

on both sides of the table, paper stacked up, words

falling off my tongue.

The robins had been a long time singing, and now it

was beginning to rain.

What are we sure of? Happiness isn’t a town on a map,

or an early arrival, or a job well done, but good work

ongoing. Which is not likely to be the trifling around

with a poem.

Then it began raining hard, and the flowers in the yard

were full of lively fragrance.

You have had days like this, no doubt. And wasn’t it

wonderful, finally, to leave the room? Ah, what a

moment!

As for myself, I swung the door open. And there was

the wordless, singing world. And I ran for my life.

“Search corrects your knowledge, browsing corrects your ignorance.” Soon we will turn again to the opening of Genesis and the beginning of the Torah. I look forward to another year of browsing its chapters.

And I do know this as well. I look forward to where this browsing might carry me.

That door never closes. My sadness is lifted.

Judaism and Abortion Rights

Given the recent decision of the US Supreme Court to let the Texas law stand that effectively blocks access to abortions after six weeks, I thought it important to lay out the Jewish view of abortion. After the holidays, we will host a panel examining this recent Supreme Court decision and Roe v. Wade. We are fortunate to have among our members Robin Charlow, a professor of law at Hofstra University and Lauren Riese Garfunkel, a Board member of the National Council of Jewish Women. They will help walk us through the constitutional issues and what more can be done in the fight for reproductive freedom.

This morning I will turn to the texts of our tradition. For those who are regulars at our second day Rosh Hashanah service, you know it is my custom to examine Judaism’s sacred texts. This is what I will walk us through this morning. Here are the three crucial texts elucidating the Jewish view of abortion. First an aside. As Jews we are informed by our sacred texts. We are guided by their words. We don’t just make decisions without looking to the wisdom of those who went before us. First and foremost, we look to the Torah.

Here are the words of the Torah, from Parashat Mishpatim in the Book of Exodus.

“When men fight, and one of them pushes a pregnant woman and a miscarriage result, but no other damage ensues, the one responsible shall be fined according as the woman’s husband may exact from him, the payment to be based on reckoning. But if other damage ensues, the penalty shall be life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise. (Exodus 21)

Here are the crucial take-aways from this foundational text.

1. The fetus is not considered a life. The loss of the pregnancy is considered a damage and not murder. Note that this is the context for the often-misunderstood Biblical phrase an “eye for an eye.” That phrase does not mean as contemporary culture would suggest that vengeance should be exacted but instead, we assign damages commensurate with the value of what is lost. The value of a life for a life, an eye for an eye and so on. If the person’s arm is broken for instance, the compensation is standardized: hand for hand.

2. While it may seem unfeeling to refer to miscarriages as damages, most especially to anyone who has lost a pregnancy, this establishes the Jewish hierarchy of values. The fetus is not the same as a person. It is also unfeeling, and I would deem wrong and misguided, to treat women as a husband’s property. I would like to think we corrected this biblical view. Unfortunately, it appears this view has not changed as much as we might have thought. All I can say for sure is that it has changed here.

Next an early rabbinic text. This is from the Mishnah, completed in the early third century CE. The Mishnah forms the first layer of the Talmud. This rabbinic text forms the basis for what we know and call Judaism. That is the book that continues to shape us. This informs Jewish law.

The rabbis teach:

“A woman who was having trouble giving birth, they cut up the fetus inside her and take it out limb by limb, because her life comes before its life. If most of it had come out already, they do not touch it because we do not push off one life for another.” (Ohalot 7)

Here are the important insights we derive from the Mishnah:

1. The life of the mother comes before the life of the fetus. The fetus only gains equal standing with that of the mother’s once it is born or at least almost fully emerges. Rabbinic law equates life with breath, with the Hebrew word neshama meaning both soul and breath.

2. Abortion is allowed until the very end of pregnancy. It is not limited to the first trimester. In fact, abortion is required if a woman life is endangered by the pregnancy.

3. Later rabbinic law debates what constitutes a threat to the mother’s life. Traditional authorities only allow for physical threats. In other words, they are only comfortable allowing abortions if the mother is in danger of dying. More liberal authorities allow for any threat, physical, emotional, psychological and even financial. Liberal Jews argue for its permissibility in the case of rape and incest.

4. Rabbis argue about those details. To be honest, too often those rabbis are still very much men who never bother to consult or listen to women whose bodies they continue to objectify and talk about as if they are their property.

And finally, from the very first chapter of the Bible, the Book of Genesis:

“And God created human beings in God’s image, in the image of God, God created human; male and female God created them.” (Genesis 1)

1. Human beings are created in the divine image.

2. Jewish teaching expounds on this. Our bodies are a reflection of the divine. They are holy because of this image. According to Jewish law, we are not permitted to do whatever we want to our bodies, whether that be piercings, tattoos, surgeries, cremations or in this case abortions.

3. Only if we are saving life is an abortion permitted. The details of what constitutes a threat to life in the case of abortion is debated even among physicians. Different people will have different views about what constitutes a threat to the mother’s life.

Those are the Jewish texts that inform the Jewish view about abortion. Let me summarize their teachings and then give you my own view. First of all because I am a rabbi. And second because I am a man and so I am going to tell you what I think is right.

Judaism does not believe human life begins at conception but instead at birth. The fetus is holy and is considered a life but is not of equal standing to that of the mother. Of course, creating a life is sacred and we should not treat in a cavalier manner. We should look at this as a divine blessing. Neither should we treat a mother’s life in a cavalier manner. The human body too is holy and should be cared for as if it a vessel of the divine. It is not to be worshipped but should be seen as containing God’s reflection.

Herein lies the crux of the problem, most especially with how we discuss abortion rights in our own country. Too often the debate is portrayed as pitting those who believe in God and God’s creation against those who don’t believe. On one side are those who believe we should have reverence for life and on the other are those who think we should be able to do whatever we want when we want.

Our tradition teaches us otherwise. It affirms that the baby forming within a mother’s womb is sacred but not as sacred as the mother’s life. If a terrible choice has to be made between the two, then Judaism teaches that we choose the mother’s life. Of course, every situation is nuanced and complicated which is why we should leave such decisions to a woman. Ideally, she would be able to consult with her partner. But let’s be clear, she can better navigate and assess what the dangers to her own life might be. I hope she might be informed by the advice of doctors and the wisdom of her own faith.

I believe in life. First that of the mother. And second that of the fetus. That is an obvious hierarchy. It is what my Jewish faith teaches me.

My primary objection to the state limiting access to abortions is that it is forcing upon women a religious world view different than our own. It is insisting that women must carry the burdens, and consequences, of a faith they may or may not believe in. And who by the way am I to offer any counsel or wisdom on this matter? I never tossed and turned at night, unable to get comfortable because of my growing belly. All I ever did was make a lot of smoothies for nine months.

And yet here is my pledge. I will fight to unshackle women from a world view not of their own choosing. Do not tell them you know what’s best for them. Let women decide how to navigate such difficult decisions in a manner of their own choosing. I pledge. I am in this fight so that everyone can say, “This is what I believe. This is what my tradition teaches.” And so, this is the decision I choose.

We must stay in this fight and likewise affirm the mother’s life and the importance of our Jewish faith.

Changing Our Perspective

Let’s turn around and examine the past. Let’s figure out what Jewish lessons we can discern from this painful year. On this Rosh Hashanah let’s focus on the outside world. Let’s look at contemporary events. Judaism offers us help. It offers us answers for how we can make sense of our reeling world. We need our Judaism to offer us a way out of all these messes. This morning let’s look out. Let’s look back. We begin with the last weeks. This morning let’s tackle just two recent events: the Hurricane and Afghanistan. Tomorrow morning, I will examine abortion rights.

Hurricane Ida. In case seven inches of rain, streets transformed into rivers, people drowning in their apartments as well as cars, didn’t convince us, climate change is real. In case the drought that plagues the American West, the Colorado River drying up, forest fires producing so much smoke and toxic fumes that we choke on it here in New York, didn’t convince us, climate change has already happened. The weather is changing before our eyes. I watch the Weather Channel more than the news. My phone flashes more alerts for weather emergencies than Instagram DM’s. Ok, that may have more to do with the fact that I am no longer in high school, but you get my point. When Ida rolled through our area, my phone wailed with alarms. Tornado warnings. Flash flood emergencies.

And we should be wailing just as loudly as those sirens. We should not be screaming about what one political party is doing better than the other. Do you think the weather is partisan? Here is the simple but brutal truth. We can’t keep living the way we live and expect that we won’t pay the price. Sure, my new generator might insulate me from the challenges of the next storm. Now, if my house loses power once again—and you know that it is going to happen with more frequency—then at least I can have heat when this coming winter delivers feet of snow rather than inches. What about the millions, no billions, of people who cannot afford such luxuries? Open your heart, rabbi! Think about others. 70% of New Orleans still did not have electricity by the beginning of Labor Day weekend! Nearly 1 in 3 Americans were affected by a weather disaster this summer. Something has to change. Actually, let’s say that better, we have to change. It is up to us.

And what does Judaism say about all this? It teaches that we are custodians of the world, that we must care for this big, beautiful, and nourishing divine gift. It also teaches, and this is the most important and fundamental point, that the land does not belong to us. We don’t own it. The earth is borrowed. We are tenants. We are living on someone else’s property. We are living in God’s house. That shift is the crucial change we must make in how we view the world. If we start with the premise that this is mine, that I own this plot of land or this piece of property, then it follows that I can do anything I want with it. I can tear down this tree or plant these flowers or enlarge my kitchen or extend my driveway. Some might respond, “Well first you have to ask the zoning board.”

But that Long Island reality of town boards to which we go for approvals is not equal to what Judaism says. Our tradition wants us to ask these questions, “What do the birds say? What does the land require? What do the animals need? What crops should be grown on Long Island?” If the earth is ours—and I mean ours in the sense of every living thing that God created—then the question is not about my wants or my desires but instead about all of our needs. If we ask, not what do I want but what does the earth need if even just a few more times, if we focus less on what do I want but instead what does God’s beautiful, but obviously crumbling, house need, then we will be better off. If we ask this question just once a week in the coming year, we will perhaps have brought some measure of healing to all this hurt. We have to shift our perspective.

Sure, it is about replacing our lightbulbs with LED bulbs and maybe even driving a Tesla or fighting to make sure that more of our power plants use renewable energy, and advocating our cities have a lot more green spaces to help absorb all of this water or bike lanes to help reduce car pollution. It is about working to reduce our carbon footprint. And I am proud that our sanctuary is only illuminated by LED bulbs, but we need to be more. At this juncture, it needs to be a daily shift, or at least a weekly change. No amount of sand can save our beaches from the encroaching sea. On the East coast there will be too much water. On the West there will be too little.

Here is a rather unpopular suggestion. Eat less meat. Meat production uses far too many resources. Look to the Colorado river. Scientists suggest that if Americans avoid meat one day each week, they could save an amount of water equivalent to the entire flow of the Colorado each year and that would be more than enough water to alleviate the shortages the West is now experiencing. (The New York Times, August 27, 2021) Believe me. I like a good steak. I especially love brisket and chicken soup this time of year. Of course, I recognize that a weekly Beyond Burger is not going to save the earth. But we have to stop thinking that way. We have to stop saying, “It is too big for me to fix.” Instead, we should be asking, "How do we shift our perspective?"

Buy as much local fruits and vegetables as possible. Try to skip the blueberries in the winter and only buy them when they are in season in the Northeast. Savor the local melons you can buy at this time of year. Buy eggs at the farmers’ markets. If the answer to our children’s desperate plea for ice cream when they discover that there is none left in the freezer is to say, “Wait I will be right back.” And then we jump into the car and run out to the supermarket just to get that pint of Ben & Jerry’s (sorry, I mean Ralph’s ices) instead of saying, “I already went to the store this week. It will have to wait until the next shopping trip.” then we have not shifted our perspective. If my answer to forgetting one small item on my recent Amazon order is to order it anyway because I have Prime and the shipping is free instead of waiting at least to combine it with other items, then I have not really shifted my perspective. Just because the shipping is free and I am not charged for it, does not mean there is no cost. It’s not just about my dollars. It is instead about figuring out how we can better live in this beautiful, and wonderful, world that God created for all of us and for every living being. It not just about me and what I want right now. Everything depends on shifting our perspective.

#2. We also have to change our perspective when it comes to the war on terror. And so, this brings me to our nation’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Let me say this clearly. I am ashamed of our withdrawal from Afghanistan. It’s not that I disagree with the decision to withdraw—sadly we failed to accomplish all of our lofty goals save the original mission of taking the fight to those who attacked us on 9-11. I disagree with how we withdrew. We abandoned people who staked their lives on American idealism, who risked life and limb fighting alongside American soldiers. This is not how we should do things.

President Biden deserves credit for finally ending the war in Afghanistan, but he also deserves blame for how we left. Why was it so hard? Change the deadline. Why did we not extend the date for the troop withdrawal by months, if need be, until every one of those patriots who earned the right to be called an American if for no other reason than they fought alongside us and supported us, was brought here so that they could build the American lives they dreamed about creating. When the Torah speaks about loving the stranger it is talking about such people. It is talking about people who want to be part of our community, or in this case people who so believe in what our country stands for that they fought to become one of us.

Leadership is about owning the successes and even more importantly the failures. It is about admitting that we placed too much faith in technology and machines, in armaments and troop numbers, rather than approaching Afghan culture with humility. We failed. It saddens me to say that out loud. It angers me that the Taliban will now, almost certainly, prevent women from going to school and persecute those they consider non-believers. I still believe with all my heart that democracy, however flawed, is the best system of governing, but haven’t we learned that it can no longer be imposed by armies. Democracy has to be what Afghanistan builds for itself—sure with our help and assistance but not with our weapons. I still believe there are plenty of Afghans who want democracy, and many who wanted to come here to experience that, and we to our shame, left them at the airport—literally. We abandoned our calling. We reneged on our ideals.

This does not mean we should not have gone to Afghanistan in the first place. We sent our soldiers there to root out the terrorists who attacked us on 9-11 and the Taliban who gave them safe refuge. We have every right to attack those enemies who are bent on our destruction, who stay up late at night planning ways to kill Americans. Then our idealism blinded us. (It blinded me.) We lost our way. What does Judaism have to say about all this? Our tradition argues that a war fought in self-defense is a milchemet mitzvah, an obligatory war. That does not mean you can do whatever you want when fighting wars. That does not mean every battle is righteous. Our self-avowed enemies are human beings in our tradition’s eyes and must remain so in our own eyes. Fighting with drones, fighting from afar, blinds us to this fact. The tragic mistake we made from the very beginning and that caused us to most lose our way, was calling all of this, the war on terror. Words matter. They have consequences.

If we are not honest with ourselves about who we are fighting against, then we cannot win the war. It should be painfully obvious who we are fighting. There are people who describe themselves as America’s enemies. We went to Afghanistan to make war against Al-Qaeda. And we continue to fight against Islamic militants. Let me state what should be obvious. Our war is not with Islam, or with the millions of Muslims who find great spiritual truths in this faith, but with those fundamentalists who see the destruction of everyone and anyone who does not believe or act as they do as their religion’s purpose. Our twenty-year war was with fundamentalism in general and Islamic fundamentalism in particular. Language matters. We were confused at the beginning about who were fighting against and what we were fighting for. And so, we are confused in the end.

Here is another unpopular observation. You cannot fight a war on terror with armies. That battle can only be fought in our hearts. Terror and fear are matters of the heart. And no surgical strikes—there really is no such thing in war, or acceptable collateral damage—again there is no such thing when other human beings are killed, will assuage a fearful heart. No amount of troop deployments will safeguard us against terror. Against terrorists yes. Against terror, no. Only a proper faith can do that. Again, this is about shifting our perspective. It is about naming things in the right way. And that is up to us. It is not up to our political leaders. It is up to us.

Soldiers cannot fight our battles of the heart. Armies are supposed to protect us against those enemies who rise up against us. That has not changed since the Bible. Faith is meant to strengthen our hearts so that we can face any terror. That has also not changed since the Bible. In the Psalms, King David declares: “Should an army besiege me, my heart would have no fear; should war beset me, still would I be confident.” (Psalm 27) The shields we truly need to protect us are those that we wrap around our hearts. When we do that right we will not be afraid. Then no one can terrify us. When our armies know who they are fighting against and our hearts know what they are protecting us against, nothing can defeat us.

Get that right and we will win any struggle. It is up to us. It’s not up to President Biden or his predecessor Former President Trump. It is in our hands. And you want to know where that starts? You know how we are going to start fixing these messes and pulling ourselves out of these disasters? First things first. It is about changing our perspective and saying, “This far and no farther. I am going to do things differently.” It is going to change with me. It is not about what I want, but what the world needs. It is not about what my leaders say but more importantly what I hold in my heart.

The Talmud teaches, “What is a person asked when he or she arrives in heaven?” Among the questions. “Did you have hope for redemption?” Did you have hope in the future? Jews must never lose this hope. As hard as it is, we have to hold on to hope. And this year our hope starts with changing our perspective. Look at those wars overseas and say instead, “How do I continue the fight within me?” Look at the world not as how many pieces do I own, but what does the world need from me.

And then we can look up from this exhausting year with a measure of renewed hope. We will have gained a strengthened heart and a changed perspective. The world depends on it. The earth depends on us.

How to Help

Hurricane Ida has now passed through the New York area and left destruction and hardship in its wake. It is difficult to believe that more people were killed in our own area from what was no longer a hurricane than when the storm made landfall in Louisiana as a category 4 hurricane. I pray for those who were injured. I pray most especially for the families of those who lost their lives.

If you would like to lend support to those in need, I recommend giving to these organizations:

These organizations are already in Louisiana helping people rebuild, providing temporary shelter and feeding those who need food and even water. People are hungry! Let us help our fellow Americans.

As I became aware of those organizations who are providing help to people in need within our own area, I will share that information as well.

Give to those in need. Pray for their healing.

Wash Your Hands

Let us cast away the sin of deception, so that we will mislead no one in word or deed, nor pretend to be what we are not.Judaism counsels us that actions and deeds define our lives. Good intentions do not redeem bad deeds. Whereas bad intentions are dissolved by good deeds. Thus, we can only correct our wrong actions. We can only repair misdeeds.

Let us cast away the sin of vain ambition which prompts us to strive for goals which bring neither true fulfillment nor genuine contentment.

Let us cast away the sin of stubbornness, so that we will neither persist in foolish habits nor fail to acknowledge our will to change.

Let us cast away the sin of envy, so that we will neither be consumed by desire for what we lack nor grow unmindful of the blessings which are already ours.

Let us cast away the sin of selfishness, which keeps us from enriching our lives through wider concerns, and greater sharing, and from reaching out in love to other human beings.

Let us cast away the sin of indifference, so that we may be sensitive to the sufferings of others and responsive to the needs of our people everywhere.

Let us cast away the sin of pride and arrogance, so that we can worship God and serve God’s purposes in humility and truth. (Mahzor Hadash: The New Mahzor for Rosh Hashanah)

How many times do we instead discuss and debate intentions? Our tradition’s counsel is that they are secondary to actions. Only deeds can be judged. If a person does good, then he or she is deemed righteous. Intentions are known by God alone. What a person holds in his or her heart is the purview of the divine. It is not the province of human beings.

The High Holidays are devoted to repairing and correcting our actions. We spend these days focusing on what we might do different, not what we might intend. We resolve to cast away our wrongs and repair our lives. These days are about our hands more than our hearts.

The Torah declares: “Hidden acts concern the Lord our God; but revealed acts, it is for us and our children ever to apply all the words of this Torah.” (Deuteronomy 29)

My Father Was Lost

The implication is clear. The land is borrowed. It belongs to God. It is not owned or possessed. This is why the land’s harvest is shared first with God and then the stranger. “And you shall enjoy, together with the Levite and the stranger in your midst, all the bounty that the Lord your God has bestowed upon you and your household.”

Moreover, “oved” can be translated as “lost” rather than “fugitive” or “wandering.” Lost connotes something far more powerful. Our ancestors were not simply freed from slavery. They did not escape, but rather were lost. Abraham was not a wanderer. Instead, he was directionless—until God called to him. It was the call that set his path. It was the going out from Egypt that carved our direction.

Why begin the offering of first fruits with the recitation of these words? Why profess that our ancestor was a stranger? Why state that the founder of our faith was lost? To teach empathy for the outsider. To inculcate thanks.

Giving thanks is not about saying, “Look at the bounty with which God has blessed me.” It is instead, “Look at the bountiful blessings that I can share.” If the first fruits are borrowed from God, then there are no limits to the blessings we can share.

Recall that our ancestors wandered aimlessly. Recall that our ancestors were once strangers. And if and when we forget, we must say, “Arami oved avi.”

Say it often. Say it over and over again. Say it until it seeps into your soul.

And then say it some more.

Lost Together

We belong to a remarkable tradition. We believe that human beings are capable of change. We believe that we have the capacity to mend our ways. No one is perfect. All have erred. Let us take these precious days to mend our failures. This is the grand purpose of the upcoming High Holidays. Rosh Hashanah begins the evening of September 6th. (Yes, this is early and very soon.)

A Hasidic story that I learned from Rabbi Rami Shapiro. Reb Chaim Halberstam of Zanz once helped his disciples prepare for Elul and its goals of teshuvah (repentance) and tikkun (repair) by sharing the following tale.

Once a woman became lost in a dense forest. (Obviously this was before the advent of Google Maps.). She wandered this way and that in the hope of stumbling on a way out, but she only got more lost as the hours went by. Then she chanced upon another person walking in the woods. Hoping that he might know the way out, she said, “Can you tell me which path leads out of this forest?”

“I am sorry, but I cannot,” the man said. “I am quite lost myself.”

“You have wandered in one part of the woods,” the woman said, “while I have been lost in another. Together we may not know the way out, but we know quite a few paths that lead nowhere. Let us share what we know of the paths that fail, and then together we may find the one that succeeds.”

“What is true for these lost wanderers,” Reb Chaim said, “is true of us as well. We may not know the way out, but let us share with each other the way that have only led us back in.”

Together we are always stronger. Together we can find ourselves out of any difficulty and surmount any stumbling blocks. This year, most especially we need walk together. The path out of the forest still remains unclear, but at the very least we can wander alongside one another and be buoyed by friendship and community.

Gates of Justice

It is unfortunate that most contemporary translations render the Hebrew “shaarecha” as your settlements rather than the more literal “your gates.” The Torah proclaims: “You shall appoint magistrates and officials for your tribes, in all the settlements (shaarecha) that the Lord your God is giving you, and they shall govern the people with due justice.” (Deuteronomy 16)

The Bible’s intent is clear. Your gates are where justice is established. Why else would the Torah also instruct us “To write these words on the doorpost of your house and on your gates?” It is because justice begins, and ends, at the threshold of a house or a city. This is why justices sat and ruled at the city’s entrances.

When people debated matters of law, or had difficulties they could not resolve, they are supposed to go to judges who are more expert in the law and more experienced in rendering decisions. People, quite literally, took their disputes to the edge of town where they were resolved. In this way the community is kept whole, and differences, are kept at its outskirts. Only justice is allowed to enter through our gates.

It is a wonderful, and enlightening, image. Keep your arguments out there. Maintain your cohesiveness within. Repair to the gates when matters become heated, when it is too difficult for you to solve your problems without the assistance of a professional.

The prophet Amos declares: “Hate evil and love good. And establish justice in the gate.” (Amos 5)

If you establish justice in the gate, then your cities and towns, countries and communities, can indeed remain whole.

Get Vaccinated! It's the Jewish Thing to Do

Judaism believes that our primary responsibility is towards others. We are taught to think about the community’s needs first and foremost. A few illustrations. Attending services is about the fact that others need us to be there. We do not say, for example, the mourner’s kaddish except in the presence of a minyan of ten people. Being there is so that others can stand and mourn.

While services are most certainly meaningful and uplifting to the individual, the tradition sees their import in the “we” rather than the “I.” Our prayers are in the plural because we are only one when praying with others. Even dancing at a wedding is not so much about how the spirit (spirits?) move us but instead about making sure the couple dance and celebrate on their wedding day. It is a religious obligation to make sure that the wedding couple rejoice. I dance in large part to lift others on to the dance floor. No one can be hoisted on high for the horah unless they are surrounded by the community.

Getting vaccinated is then about making sure that we are protected and healthy. The difficulty is that we are unaccustomed to making medical decisions with anyone else in mind but ourselves. Many have been faced with difficult medical choices. Do I have the surgery as one doctor suggests or take the medicine as another recommends? Do I have the procedure or wait and see what the next blood test indicates? All such decisions are fraught with risks. No medical decision, or any choice for that matter, is risk free. Even the most ordinary of tests or procedures carry with them some risk.

But when we evaluate the pros and cons we think only of our own individual health. For the first time in many of our lives, we are now faced with a decision that is not just about my health, but also the health of others. Even though the risks of the vaccines appear minimal, they are not zero. We must admit that we could very well discover that vaccines produce unintended health consequences in the years to come. I am skeptical about this, but we must admit this.

And yet we wait to get vaccinated not only to our own detriment, but the peril of others. And this is where Judaism’s voice should be heard loudly and clearly. Get vaccinated for the sake of others. Get vaccinated so that our neighbors will remain healthy and safe. We are supposed to be about the needs of others and the community over the wants of the individual. That is Judaism’s greatest lesson and teaching.

Today’s decision is not about my health but our well-being. It is about the health of the community, and the country, and the world.

When the Jewish people enter the land of Israel, they are instructed to pronounce blessings on Mount Gerizim and curses on Mount Ebal. (Deuteronomy 11) It is not that the blessings reside on one mountain top and the curses on another. It is instead that these mountains serve as physical reminders of the good that will come from following God’s commandments and on the other hand, the consequences of disobeying the commands. The community will suffer. The people will be unable to live in the promised land if they do not follow God’s instructions.

Which mountain top will we gravitate towards? We can only choose one. And we can only choose to travel together. No one gets to go on this quest alone. The individual choice is not part of the Torah’s vocabulary. It is about the community’s will. Choice is not about what I am free to do, or not do, but instead about what we must do so that we can all thrive.

Get vaccinated. Not because it will protect you, but instead because it will protect others. There can be nothing more Jewish than rolling up your sleeves with the health and well-being of others in mind.

Earth's Bonds

In other words, follow God’s mitzvot and then it will only rain when it is supposed to rain. Nature will follow its proper course if we listen to God. (As if it were that simple!)

Too often people think that observance means lighting candles, wearing a tallis, or reciting the Shema. It also entails ethical mitzvot: loving your neighbor, giving tzedakah or honoring parents. We forget the agricultural commandments that are also part of our sacred literature. We are commanded to leave the gleanings of the field for the poor and the stranger. We are told let our fields lie fallow on the seventh year. We are enjoined not to eat fruit from trees until after the third year.

Perhaps we would do we well to rediscover the meaning and intention of these commandments. We are connected to the land. The earth gives us life.

The early Reform rabbis removed these verses, and the second paragraph of the Shema, from the prayer service arguing that it represented too literalist of a theology. It offered a stark theory. If you do good, namely listening to God, then good happens. If you do bad by ignoring God and even worse bowing down to idols, then bad happens. Everyone knows the world does not follow such a neat and simplistic order and so the rabbis said, “Better not to say these words as a prayer.”

And yet, we live in a time when we are becoming more and more aware of how fragile our earth really is. Need we look any further than the forest fires raging out West, or the catastrophic flooding in Germany and China, or the extreme heat forecast for Middle America? It seems to me that it no longer rains but only storms. Rain showers bring torrents and not droplets. It no longer rains at the rain’s appointed seasons. It no longer rains when the Torah tells us it is supposed to rain.

How we live our lives really does have bearing on whether or not the earth will continue to sustain life. This is the Torah’s insight.

I am slowly making my way through Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. If one wishes to gain inspiration from the natural world, I commend it. If one wishes to gain renewed strength, to care for our delicate, and precious, world, I urge you to pick it up. She writes: “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.”

And I am slowly, and once again, making my way through the Torah. I am slowly trying to take more of its wisdom to heart.

My relationship with the earth is indeed a sacred covenant.

Please God! Help Us Bring Peace

This week Moses begs God to change this decree: “And I pleaded (vaetchanan) with the Lord… Let me, I pray, cross over and see the good land on the other side of the Jordan.” (Deuteronomy 4)