A 9-11 Prayer

The country too was empty of words that could fill the void, that could comfort us in our horror, that could assuage the first responders’ hurt. Sure, we offered memorial services, we shared songs and poems and even prayers—as if those could somehow fill the emptiness the families who lost mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, sons and daughters, husbands and wives now felt, as if those could soften the terror we also felt now that our city no longer gleamed with its chaotic enthusiasm. Our city was emptied of its hustle and bustle save the hurried, and harried, work begun at ground zero to remove the mountains of rubble. “We must rebuild,” we shouted. And we did. “We must go after those responsible for these murders,” we cried. And we did. “We must dedicate a memorial to those lost.” Again, we did.

Mostly I remember the sky. Its vastness, its blueness, its emptiness pointed to something greater. We were empty of divisions. We were unified for a brief moment in time.

That same sky will reappear tomorrow morning on September 11, 2021. We will look up to the heavens. The planes return overhead. I no longer have to strain to hear the birds sing. We will remember the sky’s royalty. Its blue thread held us together. Now that has frayed. The divisions, and recriminations, drown out the songs. The heaven’s beauty is shrouded in grey. All we hear is blame. All we see are the pointing of fingers. That is all that fills the emptiness remaining. Fear dominates our hearts. We look at our fellow Americans and see only friend or foe. Terror captivates our thoughts. Democrats blame Republicans. Republicans blame Democrats.

We have been emptied of our solidarity. Camaraderie is cast aside.

Dear God, we pray. Offer us the strength to rebuild not just our buildings, but our nation’s common purpose. Let that regal sky blue fill our hearts so that disagreement and differences no longer become divisions.

The Torah reminds us: “Fear not. Do not be dismayed.” (Deuteronomy 31)

If we are to honor the memory of 9-11, and all those we lost, let this emptiness be dispelled. Let kinship be our abiding blessing. Let unity be our future.

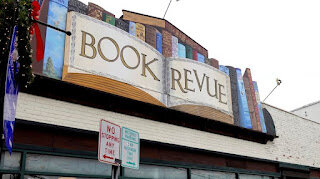

The Book (Revue) Never Closes

Tomorrow evening Huntington’s Book Revue will close its doors. Even before we moved to Huntington, we would pilgrimage there in search of books. I don’t know all the details about why it is closing. There has been plenty of online debates, and accusations, about how this was allowed to occur. I do know this. It saddens me. It is one more sadness piled on to a year of sadness.

There were countless evening outings when we would end up in Book Revue. Often, after finishing dinner at a neighborhood restaurant, we would walk around town. Inevitably we would find our way to the Book Revue. There we would often divide up and each go to our favorite sections. I usually ended up in the poetry section to see what new book had arrived. Or that destination might be chosen because Susie would say, “There is this book I want to get, let’s go see if it’s at Book Revue.” And there we would go, with friends or children in tow.

Or she might say, “I ordered something at Book Revue, let’s go pick it up.” Again, I would wander to the poetry section. I would flip through Denise Levertov, Maya Angelou, Billy Collins and Rainer Maria Rilke. On other occasions, I would lug home W.B. Yeats, Pablo Neruda, Czeslaw Milosz and Harold Bloom. It’s been eighteen years since we moved to Huntington.

I rarely if ever entered the store’s doors intending to buy another poetry book, yet the discoveries now line my shelves.

Other times we would go there with Shira and Ari. Each of us would find a corner of books to discover. Many times, we spent half of our time searching for each other trying to guess which corner Ari was exploring or which books Shira was now prying open. Inevitably Shira would find me among the poetry books (my location was predictable) and say, “I can’t find Eema and Ari.” And then we would search the bookstore together.

In which books would our family find each other?

Mary Oliver writes (there are a pile of her books from my years of travel):

I was sad all day, and why not. There I was, books piledThe Torah nears its conclusion. Moses admonishes the people: “Fear not. Do not be dismayed.” (Deuteronomy 31)

on both sides of the table, paper stacked up, words

falling off my tongue.

The robins had been a long time singing, and now it

was beginning to rain.

What are we sure of? Happiness isn’t a town on a map,

or an early arrival, or a job well done, but good work

ongoing. Which is not likely to be the trifling around

with a poem.

Then it began raining hard, and the flowers in the yard

were full of lively fragrance.

You have had days like this, no doubt. And wasn’t it

wonderful, finally, to leave the room? Ah, what a

moment!

As for myself, I swung the door open. And there was

the wordless, singing world. And I ran for my life.

“Search corrects your knowledge, browsing corrects your ignorance.” Soon we will turn again to the opening of Genesis and the beginning of the Torah. I look forward to another year of browsing its chapters.

And I do know this as well. I look forward to where this browsing might carry me.

That door never closes. My sadness is lifted.

Judaism and Abortion Rights

Given the recent decision of the US Supreme Court to let the Texas law stand that effectively blocks access to abortions after six weeks, I thought it important to lay out the Jewish view of abortion. After the holidays, we will host a panel examining this recent Supreme Court decision and Roe v. Wade. We are fortunate to have among our members Robin Charlow, a professor of law at Hofstra University and Lauren Riese Garfunkel, a Board member of the National Council of Jewish Women. They will help walk us through the constitutional issues and what more can be done in the fight for reproductive freedom.

This morning I will turn to the texts of our tradition. For those who are regulars at our second day Rosh Hashanah service, you know it is my custom to examine Judaism’s sacred texts. This is what I will walk us through this morning. Here are the three crucial texts elucidating the Jewish view of abortion. First an aside. As Jews we are informed by our sacred texts. We are guided by their words. We don’t just make decisions without looking to the wisdom of those who went before us. First and foremost, we look to the Torah.

Here are the words of the Torah, from Parashat Mishpatim in the Book of Exodus.

“When men fight, and one of them pushes a pregnant woman and a miscarriage result, but no other damage ensues, the one responsible shall be fined according as the woman’s husband may exact from him, the payment to be based on reckoning. But if other damage ensues, the penalty shall be life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise. (Exodus 21)

Here are the crucial take-aways from this foundational text.

1. The fetus is not considered a life. The loss of the pregnancy is considered a damage and not murder. Note that this is the context for the often-misunderstood Biblical phrase an “eye for an eye.” That phrase does not mean as contemporary culture would suggest that vengeance should be exacted but instead, we assign damages commensurate with the value of what is lost. The value of a life for a life, an eye for an eye and so on. If the person’s arm is broken for instance, the compensation is standardized: hand for hand.

2. While it may seem unfeeling to refer to miscarriages as damages, most especially to anyone who has lost a pregnancy, this establishes the Jewish hierarchy of values. The fetus is not the same as a person. It is also unfeeling, and I would deem wrong and misguided, to treat women as a husband’s property. I would like to think we corrected this biblical view. Unfortunately, it appears this view has not changed as much as we might have thought. All I can say for sure is that it has changed here.

Next an early rabbinic text. This is from the Mishnah, completed in the early third century CE. The Mishnah forms the first layer of the Talmud. This rabbinic text forms the basis for what we know and call Judaism. That is the book that continues to shape us. This informs Jewish law.

The rabbis teach:

“A woman who was having trouble giving birth, they cut up the fetus inside her and take it out limb by limb, because her life comes before its life. If most of it had come out already, they do not touch it because we do not push off one life for another.” (Ohalot 7)

Here are the important insights we derive from the Mishnah:

1. The life of the mother comes before the life of the fetus. The fetus only gains equal standing with that of the mother’s once it is born or at least almost fully emerges. Rabbinic law equates life with breath, with the Hebrew word neshama meaning both soul and breath.

2. Abortion is allowed until the very end of pregnancy. It is not limited to the first trimester. In fact, abortion is required if a woman life is endangered by the pregnancy.

3. Later rabbinic law debates what constitutes a threat to the mother’s life. Traditional authorities only allow for physical threats. In other words, they are only comfortable allowing abortions if the mother is in danger of dying. More liberal authorities allow for any threat, physical, emotional, psychological and even financial. Liberal Jews argue for its permissibility in the case of rape and incest.

4. Rabbis argue about those details. To be honest, too often those rabbis are still very much men who never bother to consult or listen to women whose bodies they continue to objectify and talk about as if they are their property.

And finally, from the very first chapter of the Bible, the Book of Genesis:

“And God created human beings in God’s image, in the image of God, God created human; male and female God created them.” (Genesis 1)

1. Human beings are created in the divine image.

2. Jewish teaching expounds on this. Our bodies are a reflection of the divine. They are holy because of this image. According to Jewish law, we are not permitted to do whatever we want to our bodies, whether that be piercings, tattoos, surgeries, cremations or in this case abortions.

3. Only if we are saving life is an abortion permitted. The details of what constitutes a threat to life in the case of abortion is debated even among physicians. Different people will have different views about what constitutes a threat to the mother’s life.

Those are the Jewish texts that inform the Jewish view about abortion. Let me summarize their teachings and then give you my own view. First of all because I am a rabbi. And second because I am a man and so I am going to tell you what I think is right.

Judaism does not believe human life begins at conception but instead at birth. The fetus is holy and is considered a life but is not of equal standing to that of the mother. Of course, creating a life is sacred and we should not treat in a cavalier manner. We should look at this as a divine blessing. Neither should we treat a mother’s life in a cavalier manner. The human body too is holy and should be cared for as if it a vessel of the divine. It is not to be worshipped but should be seen as containing God’s reflection.

Herein lies the crux of the problem, most especially with how we discuss abortion rights in our own country. Too often the debate is portrayed as pitting those who believe in God and God’s creation against those who don’t believe. On one side are those who believe we should have reverence for life and on the other are those who think we should be able to do whatever we want when we want.

Our tradition teaches us otherwise. It affirms that the baby forming within a mother’s womb is sacred but not as sacred as the mother’s life. If a terrible choice has to be made between the two, then Judaism teaches that we choose the mother’s life. Of course, every situation is nuanced and complicated which is why we should leave such decisions to a woman. Ideally, she would be able to consult with her partner. But let’s be clear, she can better navigate and assess what the dangers to her own life might be. I hope she might be informed by the advice of doctors and the wisdom of her own faith.

I believe in life. First that of the mother. And second that of the fetus. That is an obvious hierarchy. It is what my Jewish faith teaches me.

My primary objection to the state limiting access to abortions is that it is forcing upon women a religious world view different than our own. It is insisting that women must carry the burdens, and consequences, of a faith they may or may not believe in. And who by the way am I to offer any counsel or wisdom on this matter? I never tossed and turned at night, unable to get comfortable because of my growing belly. All I ever did was make a lot of smoothies for nine months.

And yet here is my pledge. I will fight to unshackle women from a world view not of their own choosing. Do not tell them you know what’s best for them. Let women decide how to navigate such difficult decisions in a manner of their own choosing. I pledge. I am in this fight so that everyone can say, “This is what I believe. This is what my tradition teaches.” And so, this is the decision I choose.

We must stay in this fight and likewise affirm the mother’s life and the importance of our Jewish faith.

Changing Our Perspective

Let’s turn around and examine the past. Let’s figure out what Jewish lessons we can discern from this painful year. On this Rosh Hashanah let’s focus on the outside world. Let’s look at contemporary events. Judaism offers us help. It offers us answers for how we can make sense of our reeling world. We need our Judaism to offer us a way out of all these messes. This morning let’s look out. Let’s look back. We begin with the last weeks. This morning let’s tackle just two recent events: the Hurricane and Afghanistan. Tomorrow morning, I will examine abortion rights.

Hurricane Ida. In case seven inches of rain, streets transformed into rivers, people drowning in their apartments as well as cars, didn’t convince us, climate change is real. In case the drought that plagues the American West, the Colorado River drying up, forest fires producing so much smoke and toxic fumes that we choke on it here in New York, didn’t convince us, climate change has already happened. The weather is changing before our eyes. I watch the Weather Channel more than the news. My phone flashes more alerts for weather emergencies than Instagram DM’s. Ok, that may have more to do with the fact that I am no longer in high school, but you get my point. When Ida rolled through our area, my phone wailed with alarms. Tornado warnings. Flash flood emergencies.

And we should be wailing just as loudly as those sirens. We should not be screaming about what one political party is doing better than the other. Do you think the weather is partisan? Here is the simple but brutal truth. We can’t keep living the way we live and expect that we won’t pay the price. Sure, my new generator might insulate me from the challenges of the next storm. Now, if my house loses power once again—and you know that it is going to happen with more frequency—then at least I can have heat when this coming winter delivers feet of snow rather than inches. What about the millions, no billions, of people who cannot afford such luxuries? Open your heart, rabbi! Think about others. 70% of New Orleans still did not have electricity by the beginning of Labor Day weekend! Nearly 1 in 3 Americans were affected by a weather disaster this summer. Something has to change. Actually, let’s say that better, we have to change. It is up to us.

And what does Judaism say about all this? It teaches that we are custodians of the world, that we must care for this big, beautiful, and nourishing divine gift. It also teaches, and this is the most important and fundamental point, that the land does not belong to us. We don’t own it. The earth is borrowed. We are tenants. We are living on someone else’s property. We are living in God’s house. That shift is the crucial change we must make in how we view the world. If we start with the premise that this is mine, that I own this plot of land or this piece of property, then it follows that I can do anything I want with it. I can tear down this tree or plant these flowers or enlarge my kitchen or extend my driveway. Some might respond, “Well first you have to ask the zoning board.”

But that Long Island reality of town boards to which we go for approvals is not equal to what Judaism says. Our tradition wants us to ask these questions, “What do the birds say? What does the land require? What do the animals need? What crops should be grown on Long Island?” If the earth is ours—and I mean ours in the sense of every living thing that God created—then the question is not about my wants or my desires but instead about all of our needs. If we ask, not what do I want but what does the earth need if even just a few more times, if we focus less on what do I want but instead what does God’s beautiful, but obviously crumbling, house need, then we will be better off. If we ask this question just once a week in the coming year, we will perhaps have brought some measure of healing to all this hurt. We have to shift our perspective.

Sure, it is about replacing our lightbulbs with LED bulbs and maybe even driving a Tesla or fighting to make sure that more of our power plants use renewable energy, and advocating our cities have a lot more green spaces to help absorb all of this water or bike lanes to help reduce car pollution. It is about working to reduce our carbon footprint. And I am proud that our sanctuary is only illuminated by LED bulbs, but we need to be more. At this juncture, it needs to be a daily shift, or at least a weekly change. No amount of sand can save our beaches from the encroaching sea. On the East coast there will be too much water. On the West there will be too little.

Here is a rather unpopular suggestion. Eat less meat. Meat production uses far too many resources. Look to the Colorado river. Scientists suggest that if Americans avoid meat one day each week, they could save an amount of water equivalent to the entire flow of the Colorado each year and that would be more than enough water to alleviate the shortages the West is now experiencing. (The New York Times, August 27, 2021) Believe me. I like a good steak. I especially love brisket and chicken soup this time of year. Of course, I recognize that a weekly Beyond Burger is not going to save the earth. But we have to stop thinking that way. We have to stop saying, “It is too big for me to fix.” Instead, we should be asking, "How do we shift our perspective?"

Buy as much local fruits and vegetables as possible. Try to skip the blueberries in the winter and only buy them when they are in season in the Northeast. Savor the local melons you can buy at this time of year. Buy eggs at the farmers’ markets. If the answer to our children’s desperate plea for ice cream when they discover that there is none left in the freezer is to say, “Wait I will be right back.” And then we jump into the car and run out to the supermarket just to get that pint of Ben & Jerry’s (sorry, I mean Ralph’s ices) instead of saying, “I already went to the store this week. It will have to wait until the next shopping trip.” then we have not shifted our perspective. If my answer to forgetting one small item on my recent Amazon order is to order it anyway because I have Prime and the shipping is free instead of waiting at least to combine it with other items, then I have not really shifted my perspective. Just because the shipping is free and I am not charged for it, does not mean there is no cost. It’s not just about my dollars. It is instead about figuring out how we can better live in this beautiful, and wonderful, world that God created for all of us and for every living being. It not just about me and what I want right now. Everything depends on shifting our perspective.

#2. We also have to change our perspective when it comes to the war on terror. And so, this brings me to our nation’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Let me say this clearly. I am ashamed of our withdrawal from Afghanistan. It’s not that I disagree with the decision to withdraw—sadly we failed to accomplish all of our lofty goals save the original mission of taking the fight to those who attacked us on 9-11. I disagree with how we withdrew. We abandoned people who staked their lives on American idealism, who risked life and limb fighting alongside American soldiers. This is not how we should do things.

President Biden deserves credit for finally ending the war in Afghanistan, but he also deserves blame for how we left. Why was it so hard? Change the deadline. Why did we not extend the date for the troop withdrawal by months, if need be, until every one of those patriots who earned the right to be called an American if for no other reason than they fought alongside us and supported us, was brought here so that they could build the American lives they dreamed about creating. When the Torah speaks about loving the stranger it is talking about such people. It is talking about people who want to be part of our community, or in this case people who so believe in what our country stands for that they fought to become one of us.

Leadership is about owning the successes and even more importantly the failures. It is about admitting that we placed too much faith in technology and machines, in armaments and troop numbers, rather than approaching Afghan culture with humility. We failed. It saddens me to say that out loud. It angers me that the Taliban will now, almost certainly, prevent women from going to school and persecute those they consider non-believers. I still believe with all my heart that democracy, however flawed, is the best system of governing, but haven’t we learned that it can no longer be imposed by armies. Democracy has to be what Afghanistan builds for itself—sure with our help and assistance but not with our weapons. I still believe there are plenty of Afghans who want democracy, and many who wanted to come here to experience that, and we to our shame, left them at the airport—literally. We abandoned our calling. We reneged on our ideals.

This does not mean we should not have gone to Afghanistan in the first place. We sent our soldiers there to root out the terrorists who attacked us on 9-11 and the Taliban who gave them safe refuge. We have every right to attack those enemies who are bent on our destruction, who stay up late at night planning ways to kill Americans. Then our idealism blinded us. (It blinded me.) We lost our way. What does Judaism have to say about all this? Our tradition argues that a war fought in self-defense is a milchemet mitzvah, an obligatory war. That does not mean you can do whatever you want when fighting wars. That does not mean every battle is righteous. Our self-avowed enemies are human beings in our tradition’s eyes and must remain so in our own eyes. Fighting with drones, fighting from afar, blinds us to this fact. The tragic mistake we made from the very beginning and that caused us to most lose our way, was calling all of this, the war on terror. Words matter. They have consequences.

If we are not honest with ourselves about who we are fighting against, then we cannot win the war. It should be painfully obvious who we are fighting. There are people who describe themselves as America’s enemies. We went to Afghanistan to make war against Al-Qaeda. And we continue to fight against Islamic militants. Let me state what should be obvious. Our war is not with Islam, or with the millions of Muslims who find great spiritual truths in this faith, but with those fundamentalists who see the destruction of everyone and anyone who does not believe or act as they do as their religion’s purpose. Our twenty-year war was with fundamentalism in general and Islamic fundamentalism in particular. Language matters. We were confused at the beginning about who were fighting against and what we were fighting for. And so, we are confused in the end.

Here is another unpopular observation. You cannot fight a war on terror with armies. That battle can only be fought in our hearts. Terror and fear are matters of the heart. And no surgical strikes—there really is no such thing in war, or acceptable collateral damage—again there is no such thing when other human beings are killed, will assuage a fearful heart. No amount of troop deployments will safeguard us against terror. Against terrorists yes. Against terror, no. Only a proper faith can do that. Again, this is about shifting our perspective. It is about naming things in the right way. And that is up to us. It is not up to our political leaders. It is up to us.

Soldiers cannot fight our battles of the heart. Armies are supposed to protect us against those enemies who rise up against us. That has not changed since the Bible. Faith is meant to strengthen our hearts so that we can face any terror. That has also not changed since the Bible. In the Psalms, King David declares: “Should an army besiege me, my heart would have no fear; should war beset me, still would I be confident.” (Psalm 27) The shields we truly need to protect us are those that we wrap around our hearts. When we do that right we will not be afraid. Then no one can terrify us. When our armies know who they are fighting against and our hearts know what they are protecting us against, nothing can defeat us.

Get that right and we will win any struggle. It is up to us. It’s not up to President Biden or his predecessor Former President Trump. It is in our hands. And you want to know where that starts? You know how we are going to start fixing these messes and pulling ourselves out of these disasters? First things first. It is about changing our perspective and saying, “This far and no farther. I am going to do things differently.” It is going to change with me. It is not about what I want, but what the world needs. It is not about what my leaders say but more importantly what I hold in my heart.

The Talmud teaches, “What is a person asked when he or she arrives in heaven?” Among the questions. “Did you have hope for redemption?” Did you have hope in the future? Jews must never lose this hope. As hard as it is, we have to hold on to hope. And this year our hope starts with changing our perspective. Look at those wars overseas and say instead, “How do I continue the fight within me?” Look at the world not as how many pieces do I own, but what does the world need from me.

And then we can look up from this exhausting year with a measure of renewed hope. We will have gained a strengthened heart and a changed perspective. The world depends on it. The earth depends on us.

How to Help

Hurricane Ida has now passed through the New York area and left destruction and hardship in its wake. It is difficult to believe that more people were killed in our own area from what was no longer a hurricane than when the storm made landfall in Louisiana as a category 4 hurricane. I pray for those who were injured. I pray most especially for the families of those who lost their lives.

If you would like to lend support to those in need, I recommend giving to these organizations:

These organizations are already in Louisiana helping people rebuild, providing temporary shelter and feeding those who need food and even water. People are hungry! Let us help our fellow Americans.

As I became aware of those organizations who are providing help to people in need within our own area, I will share that information as well.

Give to those in need. Pray for their healing.

Wash Your Hands

Let us cast away the sin of deception, so that we will mislead no one in word or deed, nor pretend to be what we are not.Judaism counsels us that actions and deeds define our lives. Good intentions do not redeem bad deeds. Whereas bad intentions are dissolved by good deeds. Thus, we can only correct our wrong actions. We can only repair misdeeds.

Let us cast away the sin of vain ambition which prompts us to strive for goals which bring neither true fulfillment nor genuine contentment.

Let us cast away the sin of stubbornness, so that we will neither persist in foolish habits nor fail to acknowledge our will to change.

Let us cast away the sin of envy, so that we will neither be consumed by desire for what we lack nor grow unmindful of the blessings which are already ours.

Let us cast away the sin of selfishness, which keeps us from enriching our lives through wider concerns, and greater sharing, and from reaching out in love to other human beings.

Let us cast away the sin of indifference, so that we may be sensitive to the sufferings of others and responsive to the needs of our people everywhere.

Let us cast away the sin of pride and arrogance, so that we can worship God and serve God’s purposes in humility and truth. (Mahzor Hadash: The New Mahzor for Rosh Hashanah)

How many times do we instead discuss and debate intentions? Our tradition’s counsel is that they are secondary to actions. Only deeds can be judged. If a person does good, then he or she is deemed righteous. Intentions are known by God alone. What a person holds in his or her heart is the purview of the divine. It is not the province of human beings.

The High Holidays are devoted to repairing and correcting our actions. We spend these days focusing on what we might do different, not what we might intend. We resolve to cast away our wrongs and repair our lives. These days are about our hands more than our hearts.

The Torah declares: “Hidden acts concern the Lord our God; but revealed acts, it is for us and our children ever to apply all the words of this Torah.” (Deuteronomy 29)

My Father Was Lost

The implication is clear. The land is borrowed. It belongs to God. It is not owned or possessed. This is why the land’s harvest is shared first with God and then the stranger. “And you shall enjoy, together with the Levite and the stranger in your midst, all the bounty that the Lord your God has bestowed upon you and your household.”

Moreover, “oved” can be translated as “lost” rather than “fugitive” or “wandering.” Lost connotes something far more powerful. Our ancestors were not simply freed from slavery. They did not escape, but rather were lost. Abraham was not a wanderer. Instead, he was directionless—until God called to him. It was the call that set his path. It was the going out from Egypt that carved our direction.

Why begin the offering of first fruits with the recitation of these words? Why profess that our ancestor was a stranger? Why state that the founder of our faith was lost? To teach empathy for the outsider. To inculcate thanks.

Giving thanks is not about saying, “Look at the bounty with which God has blessed me.” It is instead, “Look at the bountiful blessings that I can share.” If the first fruits are borrowed from God, then there are no limits to the blessings we can share.

Recall that our ancestors wandered aimlessly. Recall that our ancestors were once strangers. And if and when we forget, we must say, “Arami oved avi.”

Say it often. Say it over and over again. Say it until it seeps into your soul.

And then say it some more.

Lost Together

We belong to a remarkable tradition. We believe that human beings are capable of change. We believe that we have the capacity to mend our ways. No one is perfect. All have erred. Let us take these precious days to mend our failures. This is the grand purpose of the upcoming High Holidays. Rosh Hashanah begins the evening of September 6th. (Yes, this is early and very soon.)

A Hasidic story that I learned from Rabbi Rami Shapiro. Reb Chaim Halberstam of Zanz once helped his disciples prepare for Elul and its goals of teshuvah (repentance) and tikkun (repair) by sharing the following tale.

Once a woman became lost in a dense forest. (Obviously this was before the advent of Google Maps.). She wandered this way and that in the hope of stumbling on a way out, but she only got more lost as the hours went by. Then she chanced upon another person walking in the woods. Hoping that he might know the way out, she said, “Can you tell me which path leads out of this forest?”

“I am sorry, but I cannot,” the man said. “I am quite lost myself.”

“You have wandered in one part of the woods,” the woman said, “while I have been lost in another. Together we may not know the way out, but we know quite a few paths that lead nowhere. Let us share what we know of the paths that fail, and then together we may find the one that succeeds.”

“What is true for these lost wanderers,” Reb Chaim said, “is true of us as well. We may not know the way out, but let us share with each other the way that have only led us back in.”

Together we are always stronger. Together we can find ourselves out of any difficulty and surmount any stumbling blocks. This year, most especially we need walk together. The path out of the forest still remains unclear, but at the very least we can wander alongside one another and be buoyed by friendship and community.

Gates of Justice

It is unfortunate that most contemporary translations render the Hebrew “shaarecha” as your settlements rather than the more literal “your gates.” The Torah proclaims: “You shall appoint magistrates and officials for your tribes, in all the settlements (shaarecha) that the Lord your God is giving you, and they shall govern the people with due justice.” (Deuteronomy 16)

The Bible’s intent is clear. Your gates are where justice is established. Why else would the Torah also instruct us “To write these words on the doorpost of your house and on your gates?” It is because justice begins, and ends, at the threshold of a house or a city. This is why justices sat and ruled at the city’s entrances.

When people debated matters of law, or had difficulties they could not resolve, they are supposed to go to judges who are more expert in the law and more experienced in rendering decisions. People, quite literally, took their disputes to the edge of town where they were resolved. In this way the community is kept whole, and differences, are kept at its outskirts. Only justice is allowed to enter through our gates.

It is a wonderful, and enlightening, image. Keep your arguments out there. Maintain your cohesiveness within. Repair to the gates when matters become heated, when it is too difficult for you to solve your problems without the assistance of a professional.

The prophet Amos declares: “Hate evil and love good. And establish justice in the gate.” (Amos 5)

If you establish justice in the gate, then your cities and towns, countries and communities, can indeed remain whole.

Get Vaccinated! It's the Jewish Thing to Do

Judaism believes that our primary responsibility is towards others. We are taught to think about the community’s needs first and foremost. A few illustrations. Attending services is about the fact that others need us to be there. We do not say, for example, the mourner’s kaddish except in the presence of a minyan of ten people. Being there is so that others can stand and mourn.

While services are most certainly meaningful and uplifting to the individual, the tradition sees their import in the “we” rather than the “I.” Our prayers are in the plural because we are only one when praying with others. Even dancing at a wedding is not so much about how the spirit (spirits?) move us but instead about making sure the couple dance and celebrate on their wedding day. It is a religious obligation to make sure that the wedding couple rejoice. I dance in large part to lift others on to the dance floor. No one can be hoisted on high for the horah unless they are surrounded by the community.

Getting vaccinated is then about making sure that we are protected and healthy. The difficulty is that we are unaccustomed to making medical decisions with anyone else in mind but ourselves. Many have been faced with difficult medical choices. Do I have the surgery as one doctor suggests or take the medicine as another recommends? Do I have the procedure or wait and see what the next blood test indicates? All such decisions are fraught with risks. No medical decision, or any choice for that matter, is risk free. Even the most ordinary of tests or procedures carry with them some risk.

But when we evaluate the pros and cons we think only of our own individual health. For the first time in many of our lives, we are now faced with a decision that is not just about my health, but also the health of others. Even though the risks of the vaccines appear minimal, they are not zero. We must admit that we could very well discover that vaccines produce unintended health consequences in the years to come. I am skeptical about this, but we must admit this.

And yet we wait to get vaccinated not only to our own detriment, but the peril of others. And this is where Judaism’s voice should be heard loudly and clearly. Get vaccinated for the sake of others. Get vaccinated so that our neighbors will remain healthy and safe. We are supposed to be about the needs of others and the community over the wants of the individual. That is Judaism’s greatest lesson and teaching.

Today’s decision is not about my health but our well-being. It is about the health of the community, and the country, and the world.

When the Jewish people enter the land of Israel, they are instructed to pronounce blessings on Mount Gerizim and curses on Mount Ebal. (Deuteronomy 11) It is not that the blessings reside on one mountain top and the curses on another. It is instead that these mountains serve as physical reminders of the good that will come from following God’s commandments and on the other hand, the consequences of disobeying the commands. The community will suffer. The people will be unable to live in the promised land if they do not follow God’s instructions.

Which mountain top will we gravitate towards? We can only choose one. And we can only choose to travel together. No one gets to go on this quest alone. The individual choice is not part of the Torah’s vocabulary. It is about the community’s will. Choice is not about what I am free to do, or not do, but instead about what we must do so that we can all thrive.

Get vaccinated. Not because it will protect you, but instead because it will protect others. There can be nothing more Jewish than rolling up your sleeves with the health and well-being of others in mind.

Earth's Bonds

In other words, follow God’s mitzvot and then it will only rain when it is supposed to rain. Nature will follow its proper course if we listen to God. (As if it were that simple!)

Too often people think that observance means lighting candles, wearing a tallis, or reciting the Shema. It also entails ethical mitzvot: loving your neighbor, giving tzedakah or honoring parents. We forget the agricultural commandments that are also part of our sacred literature. We are commanded to leave the gleanings of the field for the poor and the stranger. We are told let our fields lie fallow on the seventh year. We are enjoined not to eat fruit from trees until after the third year.

Perhaps we would do we well to rediscover the meaning and intention of these commandments. We are connected to the land. The earth gives us life.

The early Reform rabbis removed these verses, and the second paragraph of the Shema, from the prayer service arguing that it represented too literalist of a theology. It offered a stark theory. If you do good, namely listening to God, then good happens. If you do bad by ignoring God and even worse bowing down to idols, then bad happens. Everyone knows the world does not follow such a neat and simplistic order and so the rabbis said, “Better not to say these words as a prayer.”

And yet, we live in a time when we are becoming more and more aware of how fragile our earth really is. Need we look any further than the forest fires raging out West, or the catastrophic flooding in Germany and China, or the extreme heat forecast for Middle America? It seems to me that it no longer rains but only storms. Rain showers bring torrents and not droplets. It no longer rains at the rain’s appointed seasons. It no longer rains when the Torah tells us it is supposed to rain.

How we live our lives really does have bearing on whether or not the earth will continue to sustain life. This is the Torah’s insight.

I am slowly making my way through Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. If one wishes to gain inspiration from the natural world, I commend it. If one wishes to gain renewed strength, to care for our delicate, and precious, world, I urge you to pick it up. She writes: “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.”

And I am slowly, and once again, making my way through the Torah. I am slowly trying to take more of its wisdom to heart.

My relationship with the earth is indeed a sacred covenant.

Please God! Help Us Bring Peace

This week Moses begs God to change this decree: “And I pleaded (vaetchanan) with the Lord… Let me, I pray, cross over and see the good land on the other side of the Jordan.” (Deuteronomy 4)

The commentators are bothered by Moses’ behavior. They think it is unbecoming that Moses pleads. How can the great Moses sink to such a level and beg, they wonder. His words seem undignified for a leader. They wonder as well how Moses can question God’s judgment.

The medieval writer, Moses ibn Ezra, suggests that even in this instance, Moses, who the tradition calls “Moshe Rabbeinu—Moses, our teacher,” is offering a lesson. And what is it that he teaches the people? It is a lesson about the supreme value of living in the land of Israel. It is as if to say, “To be able to live in the land of Israel is worth it. It is such a privilege that one can beg and plead.”

The modern commentator, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, reads this passage differently. He suggests that Moses is not asking for forgiveness, or pleading his case, but instead arguing that he did not even commit a wrong. The decree is unjustified and should rightfully be annulled. What chutzpah!

In the end Moses’ request is partially fulfilled. God responds to his plea and allows him to see the land from afar. Moses is allowed to glimpse the beauty of Eretz Yisrael, the land of Israel.

I continue to wonder. For what is it appropriate to plead? For what can I beg God?

This summer suggests an answer. How about peace? Let my plea be heard! Let shalom be granted—even if but partially. Let us stop arguing about whether or not we should eat Ben & Jerry’s ice cream and start doing the hard work of trying to make peace between Israelis and Palestinians. Does such a plea appear undignified? Does such a dream seem impossible? Please God, I beg You, let it not be so.

I lean on the Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai.

Not the peace of a cease-fire

not even the vision of the wolf and the lamb,

but rather

as in the heart when the excitement is over

and you can talk only about a great weariness.

I know that I know how to kill,

that makes me an adult.

And my son plays with a toy gun that knows

how to open and close its eyes and say Mama.

A peace

without the big noise of beating swords into ploughshares,

without words, without

the thud of the heavy rubber stamp: let it be

light, floating, like lazy white foam.

A little rest for the wounds –

who speaks of healing?

(And the howl of orphans is passed from generation

to the next, as in a relay race:

the baton never falls.)

Let it come

-like wildflowers,

suddenly, because the field

must have it: wildpeace.

Teach in All Languages

years old and is told he must relinquish his leadership to Joshua. Soon he will die and be buried on Mount Nebo, on the other side of the Jordan. Beforehand he takes the time (pretty much the entire book of Deuteronomy) to remind the Israelites about the many rules they must follow. He begins by reviewing their adventures (and misadventures) during their forty years of wandering the wilderness.

This is Deuteronomy’s plot. “I am about to leave you. Don’t forget to…” The Torah states: “On the other side of the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to expound this Torah.” (Deuteronomy 1)

The rabbis ask: How did he begin to teach the Torah? Being rabbis they answer their own question and state, “Moses began to explain the Torah in the seventy languages of the ancient world.”

Didn’t the Israelites all speak the same language? Didn’t they speak Hebrew? Of course they did. So why would Moses need to explain the Torah in every language the rabbis believed to exist in the entire world? It is because the Torah has universal import.

Too often we focus our Jewish learning on the mastery of the Hebrew language. Too often we mistake the Torah’s language for its essence. While Hebrew is of course important it does not always unlock its secrets; it cannot always unravel its mysteries. This is why even Moses taught the Torah in many languages.

The lesson is clear. The most important thing about Torah is its teachings. These must be translated into every language. Moreover, these teachings must be interpreted according to everyone’s ability.

Torah was never meant to belong to a privileged few. It is meant for all. It is meant for the world.

It begins with whatever language we speak.

Rejoice and Be Glad

And then my heart will most certainly rejoice.

Few realize that the words to this familiar song are not that old. In fact, the tune is based on a Hasidic niggun, prevalent among Jews living in nineteenth century Ukraine. And many nigguns are based on what was then popular songs. The Hasidic rebbes removed the words from these songs and transformed them into wordless, religious melodies.

Hava Nagila is no different. It is apparently very similar to a Ukrainian folk song.

The Hasidic movement gave these wordless melodies meaning and import. They were known to sing them over and over, their voices growing softer and then louder. They would sing and dance to welcome Shabbat, to rejoice at a holiday’s arrival, to celebrate a young couple getting married. They were passed from one generation to the next. They are typically attributed to specific rebbes. It was the belief of Hasidic Jews that singing helps connect us to God. Music is the universal language. It was also their belief that no words can suffice in approaching God and so we are left with their wordless melodies.

And so, the Hava Nagila tune was carried by such Hasidic Jews when they came to Jerusalem from the Ukraine. It was there that Abraham Idelsohn soon discovered it.

He is considered the dean of Jewish musicologists. Some believe that he authored the accompanying words in 1918 to celebrate the victory of the British in World War I. The song soon spread throughout Palestine and then made its way to the United States.

By the 1950’s it had become what we recognize today: the staple at Jewish parties and simchas.

There is nothing quite like it. Despite the song’s relative youth—at least as measured against Jewish history, it has come to define our celebrations.

And I am looking forward to hearing its words once gain.

The Torah reports: “These were the marches of the Israelites who started out from the land of Egypt…. They set out from…. They set out from…. They set out from…”

(Numbers 33)

I would like to think that once again our journeys, and our marches, and our lives, will again be defined, and uplifted by the simchas at which we sing and dance.

“Awaken brethren with a cheerful heart! Let us sing and be glad. Let us rejoice and be glad.”

A More Perfect Union

Its opening words stir our souls. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

And so, on this July 4th we pause to celebrate the gifts and blessings of this country, the freedoms we enjoy, unparalleled in our thousands of years of wanderings and the blessings we have garnered, unrivaled in the many nations we have called home. Here, we can freely profess our faith, here we can proudly declare our beliefs, here we can rest on the guarantees of a constitution that grants no religion primacy over another.

In this great land we can indeed enjoy life, liberty and happiness.

There is much for which to celebrate. There is much for which to give thanks.

On this July 4th we also pause to remember that this same promise has fallen short for

too many. There is still much work to be done. Our founding vision deserves to be expanded. Our founding dream must grow wider.

In the words “all men” we must hear and declare “all men and women.” And we must find renewed strength to say, “all races.” Every color, every faith, every immigrant story must become part of the American promise and dream. Our nation’s history is cluttered with examples in which the liberties enjoyed by many were also denied to many.

Pause to celebrate.

Pause to remember.

Give thanks for these United States of America.

Gather strength that this nation might indeed become a “more perfect union.”

Their Poems, Our Prayers

Denise Levertov, a British born American poet, writes in "Making Peace":

A voice from the dark called out,

‘The poets must give us

imagination of peace, to oust the intense, familiar

imagination of disaster. Peace, not only

the absence of war.’

But peace, like a poem,

is not there ahead of itself,

can’t be imagined before it is made,

can’t be known except

in the words of its making,

grammar of justice,

syntax of mutual aid.

A feeling towards it,

dimly sensing a rhythm, is all we have

until we begin to utter its metaphors,

learning them as we speak.

A line of peace might appear

if we restructured the sentence our lives are making,

revoked its reaffirmation of profit and power,

questioned our needs, allowed

long pauses . . .

A cadence of peace might balance its weight

on that different fulcrum; peace, a presence,

an energy field more intense than war,

might pulse then,

stanza by stanza into the world,

each act of living

one of its words, each word

a vibration of light—facets

of the forming crystal.

In Jerusalem, and I mean within the ancient walls,And then in this week’s portion we discover this poem:

I walk from one epoch to another without a memory

to guide me. The prophets over there are sharing

the history of the holy...ascending to heaven

and returning less discouraged and melancholy, because love

and peace are holy and are coming to town.

I was walking down a slope and thinking to myself: How

do the narrators disagree over what light said about a stone?

Is it from a dimly lit stone that wars flare up?

I walk in my sleep. I stare in my sleep. I see

no one behind me. I see no one ahead of me.

All this light is for me. I walk. I become lighter. I fly

then I become another. Transfigured. Words

sprout like grass from Isaiah’s messenger

mouth: “If you don’t believe you won’t be safe.”

I walk as if I were another. And my wound a white

biblical rose. And my hands like two doves

on the cross hovering and carrying the earth.

I don’t walk, I fly, I become another,

transfigured. No place and no time. So who am I?

I am no I in ascension’s presence. But I

think to myself: Alone, the prophet Muhammad

spoke classical Arabic. “And then what?”

Then what? A woman soldier shouted:

Is that you again? Didn’t I kill you?

I said: You killed me...and I forgot, like you, to die.

How fair are your tents, O Jacob,So said Balaam, the foreign prophet sent by Israel’s sworn enemy, the Moabites.

Your dwellings, O Israel!

Like palm-groves that stretch out,

Like gardens beside a river,

Like aloes planted by the Lord,

Like cedars beside the water…

They crouch, they lie down like a lion,

Like the king of beasts; who dare rouse them?

Blessed are they who bless you,

Accursed they who curse you! (Numbers 24)

King Balak instructs Balaam to curse the Jewish people. Instead, the prophet provides us with a prayer.

“Mah tovu ohalecha, Yaakov—How fair are your tents, O Jacob, Your dwellings, O Israel!” With these words we begin our morning prayers.

So records our Torah.

And so, we are reminded. Torah is about more than just listening to our own voice. Perhaps it is even acquired when listening to the words of our so-called enemies.

LGBTQ Rights, Juneteenth and Antisemitism

What follows is the sermon from this past Shabbat when we also marked Pride Month and Juneteenth.

But there is still unfinished business we need to get busy doing. Some people are still too hesitant to open their arms to others. People are still afraid to come out to friends, to parents, to teachers. And that is on all of us. Images are everywhere about what ideal love looks like. There is the ever-present image that an ideal couple is a man and a woman. Our tradition continues to uphold this. Our language supports this. We forget that when we idealize love, and couples in this way, we too often push aside those who are struggling with how they can measure up to what is most certainly a myth. We must make room for many, different images. We must insist that if an LGBTQ couple wishes to be married under a huppah, and sanctify their relationship, we will do so. Their love deserves to be celebrated. They deserve the hora just as much as any couple. God knows I am itching to make up for lost time and this past year bereft of dancing. We can do more. We must do more. We have traveled far, but there is still a great deal of unfinished business to which to attend.

On this Shabbat we also mark Juneteenth, now, and finally a national holiday. It was on June 19, 1865, that the last enslaved African Americans were granted freedom. Two and half years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and one month after the last of the Civil War’s battles was fought. And again, we have traveled far since that day. No one would suggest (at least not publicly) that it is permissible for human beings to be enslaved, that some people are more human than others, but as we discovered last summer this nation has more distance to travel. People still believe, or at the very least act, as if God did not create all human beings in the divine image, that God did not endow each and every one of us with God-given rights.

Black lives are not valued as much as white lives in this nation of ours. We have not reckoned with our history of slavery. We have not come to terms with the fact that there were Jews who have stood on the wrong side of history, who bought and sold men and women as slaves, who brutalized other human beings, who turned away when their Black neighbors were denied mortgages or business loans or college scholarships. Only an honest accounting of these sins, only a true reckoning of these wrongs will help lift this nation towards fulfilling its promise for all its citizens. That is what Juneteenth is supposed to be about. Let it be a day when we come to terms with these wrongs so that we may, if we cannot right them immediately, at least atone for them. Have we made progress? Yes. Is there much unfinished business still do? Yes, and yes.

And in these last months we were also reminded of another realm where we have unfinished business to get working on. Namely, tackling antisemitism. And I raise this issue on this Shabbat when we are celebrating Juneteenth and honoring Pride Month, because it reared its ugly head in the intersection of these causes. To be sure antisemitism remains a threat from the right—I have not forgotten Charlottesville or Pittsburgh; I continue to worry what violence might spill over from QAnon’s fantasies—but of late the threat has emerged from the left and this hate has emerged from the very same corners that fight for LGBTQ inclusion and advocate for Black lives.

Do not apologize for this sin of antisemitism in order to come to terms with the sin of systemic racism. Do not excuse anti-Israel diatribes in order to be more welcoming to those who identify as LGBTQ. Just because those in power continue to delegitimize LGBTQ rights, just because power has too often been used to suppress Black lives, does not mean that Israel’s exercise of power in defense of its citizens is wrong. Be clear about what we stand for. Be certain of what is right and what is wrong. Israel, like this country of ours, is a wonderful, and miraculous, nation that is imperfect but given to glorious and ennobling moments. Most Israelis want to make peace with their Palestinian neighbors and have supported many peace plans, and withdrawals from territories that too many Palestinians, most notably Hamas, have rejected. Try this in particular. Travel to Tel Aviv for the gay pride parade! Read more about Gadi Yevarkan, a Member of Knesset, who was rescued from Ethiopia in 1991.

Do not run away from the causes of ensuring that Black lives matter as much as white lives in our country or that people should be free to love and marry who they wish and who they are attracted to because some who also advocate for these rights spew antisemitic hate. Call out hatred wherever it comes from. Lift up others. Help to make our nation even greater. Help to make Israel even better. Help to make our community even stronger.

There is a lot of unfinished business to which we must attend. Yes, we have made progress, but there is still so much more we must do. Let’s get busy. Let’s never forget our most glorious Jewish teaching. Every human being is created b’tzelem Elohim, in God’s image!

First We Grieve, Then We Move Forward

A heartbreaking and unacceptable number of people didn’t survive the coronavirus. They’re gone — their own lives cut short, their loved ones still grieving their absence. But for others, the pandemic was more of an inconvenience, and for a few, it wasn’t all that inconvenient. When they talk about how excited they are about eating in restaurants again or how eager to see a movie in a theater, their voices and manners aren’t weighed down by the recognition of what the United States and other countries have been and are going through. Of the body count. Of the ruined businesses. Of the depleted bank accounts. They mostly just sense that we’re turning a corner, and they’re looking forward, not backward.I can resonate with his description of turning a corner. I share the glee and rapture of returning to the conveniences, and luxuries of years past, of children being packed up for camp, of spontaneously going out to a favorite restaurant, of hugging friends and wishing everyone a “Shabbat Shalom.” I am taken aback about the obviousness of Bruni’s cautionary note. We have this unfortunate, American tendency to avoid even talking about the hundreds of thousands who died.

If we do not figure out how to grieve for them and how to mourn our collective losses, then we will be unable to march forward.

This week we read that Miriam and Aaron die. We also read that Moses is destined to die in the wilderness, at the edge of fulfilling his life’s mission of leading the Israelites into the Promised Land. The reason why he will not cross over into the land is because he becomes angry at the people when they complain (yet again) about the food and in particular the lack of water. He strikes the rock two times rather than commanding it as God instructed him.

God commands, “You and your brother Aaron take the rod and assemble the community, and before their very eyes order the rock to yield its water.” (Numbers 20) Instead Moses hits the rock and says, “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?" Because Moses does not follow God’s command, because he hits the rock in anger, because he speaks with malice towards the Israelites, he is punished. God tells him that he will not reach the Promised Land. Instead, Joshua and Caleb will take the people into the land.

Immediately preceding this event, the Torah reports the death of Miriam, Moses’ sister and the woman largely responsible for saving Moses when Pharoah decreed that all first-born Israelites are to be killed. “The Israelites arrived in a body at the wilderness of Zin on the first new moon, and the people stayed at Kadesh. Miriam died there and was buried there.”

There is no mention that mourning rituals are observed for Miriam, or that Moses grieved. The Torah appears to suggest that there was little time, that the exigencies of the moment demanded otherwise. The leader could not stop. “We have to move forward!” Moses did not pause to mourn. He did not stop to grieve. And the people’s complaining became louder and more persistent.

It is understandable that Moses lost his temper. When people are grieving their emotions are raw. Even the smallest of things can throw them curveballs. They shout at the smallest of inconveniences. They cry at the tiniest of misadventures. I understand Moses’ pain.

Then again, when people do not take the time to grieve, when they suppress those feelings of loss, and longing, in what is too often deemed, a noble effort to move forward, they hamstring their futures.

If we do not mourn, if we as a nation do not allow ourselves to grieve, we will not get to that promised land. If we do not take stock of the frightening realization that we are not immune to nature’s dangers, if we do not undertake a full accounting of the failures that contributed to more deaths than otherwise would have been the case, then we will likewise curtail a brighter future.

Open restaurants and bars are not the promised land. It is instead a fairer and more equitable society in which each of us is indeed responsible for our neighbor, and quite literally our neighbor’s health and well-being.

We can only get there, we can only cross over to this promised land, if we pause to remember.

Leadership Is About Others

On the surface Korah’s complaints appear legitimate. He, and his followers, approach Moses and Aaron and say, “You have gone too far! For all the community are holy, all of them, and the Lord is in their midst. Why then do you raise yourselves above the Lord’s congregation?” (Numbers 16)

This statement seems true. Judaism does not believe one person is holier than another. In fact, our greatest moments of holiness are achieved not when we stand alone but instead when we stand together. We require the voices of others to elevate our prayers. Moses does not hear Korah’s words as critiques but instead as threats.

He becomes distressed. Aaron becomes crestfallen. God becomes enraged. Korah and his followers are severely punished. The rebellion is mercilessly quashed. And so, the wrong, must be with Korah and his followers.

The tradition argues—at length—about Korah’s sins. What did he do to merit such punishment?

The rabbis draw inferences. They reason: “Every dispute that is for the sake of heaven, will in the end endure; but one that is not for the sake of heaven, will not endure. Which is the controversy that is for the sake of heaven? Such was the controversy of Hillel and Shammai. And which is the controversy that is not for the sake of heaven? Such was the controversy of Korah and all his followers.” (Pirke Avot 5)

When we argue with respect, when we debate so as to understand the truth standing in opposition to our own views, this is an argument for the sake of heaven, this is a controversy like that of the first century rabbis, Hillel and Shammai. When we argue, however, to destroy the opposition, when we debate so as to undermine others, these are controversies s like those of Korah and his followers.

In the rabbinic imagination, it was all about how Korah argued, and complained. In the rabbis’ estimation, it is very much about how we debate. Controversies can make the community better or they can destroy us.

Another tradition suggests Korah’s faults to be otherwise. Moses gives a hint at Korah’s sin when he says, “Do you then want the priesthood?” The tradition opines. Korah only wanted the prestige and honor of being a priest. He did not want the attendant duties and responsibilities.

Many people want honor. Few want the work that accompanies it.

Being a priest, or a politician, or a leader, or an actor, or a musician, or even a rabbi, is not so much about the prestige, but instead about the responsibilities.

History is filled with examples of rebellions, and countries led astray, by leaders who lust after the accolades, and pomp and circumstance of their positions, more than they pine after the duties to make the lives of others better.

This is what Moses teaches. This is what Korah forgets.

Leadership is supposed to be about others. It is supposed to be about lifting others up.

The Promised Land Is in Your Soul

This week when God instructs Moses to send scouts to survey the Promised Land, God similarly commands: “Shelach lecha—Send men to scout the land of Canaan, which I am giving to the Israelite people.” (Numbers 13)

In both instances the Hebrew is unusual and perhaps untranslatable. God literally states, “Go for yourself” and “Send for yourself.” Commentators note the peculiar wording and imagine novel explanations to justify this Hebrew phrasing.

One rabbinic midrash suggests that the command to Abraham was more about him finding himself than discovering a new land. Its author writes: “Go forth to find your authentic self, to learn who you are meant to be.” Is a promised land about its geographical contours or instead about unearthing some, hidden inner promise?

Is a journey, whether undertaken at God’s command or out of inner desire, about exploring new vistas or about discovering oneself?

This week we are confronted with a new question. What could Moses possibly find out about himself when commanding others to set out on a journey? He has been leading the people for years. He has been through countless tests. The people are given to lots of complaining, and rebelling (more about that in the weeks to come). This moment appears to produce an unlikely crisis of faith for our leader.

The midrash once again makes plain what the Hebrew only implies. It imagines God saying to Moses that this reconnaissance mission is more about Moses’ needs, and perhaps the people’s, rather than God’s. Our ancient rabbis fill in the gaps, found in between the Torah’s verses and write, “God seems to be saying, ‘I have you told you already that the land is good and that I will give it to you. If you need human confirmation of that, go ahead and send scouts.’”

And I wonder. Is finding oneself, and setting out on any journey, about confirming what God already intends for us or about charting some, new undiscovered territory hidden within our own soul?