No More Mourning

In 1966, the Israeli author, Shai Agnon, received the Nobel Prize in Literature. When accepting the award, he said:

It was about dreaming.

Tisha B’Av, which occurs on Sunday, commemorates a number of Jewish tragedies....

As a result of the historic catastrophe in which Titus of Rome destroyed Jerusalem and Israel was exiled from its land, I was born in one of the cities of the Exile. But always I regarded myself as one who was born in Jerusalem. In a dream, in a vision of the night, I saw myself standing with my brother-Levites in the Holy Temple, singing with them the songs of David, King of Israel, melodies such as no ear has heard since the day our city was destroyed and its people went into exile…. I was five years old when I wrote my first song. It was out of longing for my father that I wrote it.The genius and creativity spanning the 2,000 years since that historic catastrophe found its impetus in longing.

It was about dreaming.

Tisha B’Av, which occurs on Sunday, commemorates a number of Jewish tragedies....

Tell the Truth

A brief comment on some ancient, and seemingly out of date, words.

The Torah states: “Moses spoke to the heads of the Israelite tribes, saying, ‘This is what the Lord has commanded: when people make vows or take an oath, they shall not break their pledge; they must carry out all that has crossed their lips.’” (Numbers 30)

The rabbis ask, “Why did Moses speak to the heads of the tribes? Why did he direct his words to the leaders and not all the people?”

The Hatam Sofer, a leading 19th century rabbi, responds: “The reason is that it is often leaders who make all types of promises which they don’t keep. Because they often go back on their promises, this warning was aimed specifically at them.”

Such is the teaching that occurred to me when watching this week’s presidential debates.

Such is the response to those who suggest the Torah has nothing to say about our contemporary struggles.

Leaders, especially those who wish to become president, should be the most careful with their words. They should be even more careful than everyone else.

The Torah remains up to date.

The Torah states: “Moses spoke to the heads of the Israelite tribes, saying, ‘This is what the Lord has commanded: when people make vows or take an oath, they shall not break their pledge; they must carry out all that has crossed their lips.’” (Numbers 30)

The rabbis ask, “Why did Moses speak to the heads of the tribes? Why did he direct his words to the leaders and not all the people?”

The Hatam Sofer, a leading 19th century rabbi, responds: “The reason is that it is often leaders who make all types of promises which they don’t keep. Because they often go back on their promises, this warning was aimed specifically at them.”

Such is the teaching that occurred to me when watching this week’s presidential debates.

Such is the response to those who suggest the Torah has nothing to say about our contemporary struggles.

Leaders, especially those who wish to become president, should be the most careful with their words. They should be even more careful than everyone else.

The Torah remains up to date.

Passion and Zealotry

The Talmud counsels: “Rabbi Hisda taught: 'If the zealot comes to seek counsel, we never instruct him to act.'" (Sanhedrin 81b)

And yet the Torah reports that Pinchas was rewarded for his actions. Here is his story. The people are gathered on the banks of the Jordan River, poised to enter the land of Israel. They have become enthralled with the religion of the Midianites, sacrificing to their god, and participating in its festivals. Moses tries to get the Israelites to stop, issuing laws forbidding such foreign practices, but they refuse to listen. God becomes enraged.

"Just then one of the Israelites came and brought a Midianite woman over to his companions... When Pinchas saw this he left the assembly and taking a spear in his hand he followed the Israelite into the chamber and stabbed both of them, the Israelite and the woman, through the belly." The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, "Pinchas has turned back My wrath from the Israelites by displaying among them his passion for Me." (Numbers 25) Pinchas' passion tempers God’s anger. Thus Pinchas renews the covenant between God and the people.

It is for this reason that Pinchas’ memory is recalled at the brit milah ceremony. As we renew the covenant through the ritual of circumcision we recall Pinchas. We then welcome the presence of the prophet Elijah who, in the future, will announce the coming of the messiah. We pray, “This is the chair of Elijah the prophet who is remembered for good.” Perhaps this young child will prove to be our people’s redeemer.

Elijah is as well a zealot. He, like Pinchas, has a violent temper and deals with non-believers with an equally heavy hand. He kills hundreds of idolaters and worshipers of Baal. So why are these the heroes we recall when we circumcise our sons? Is it possible that the rabbis saw this ritual and its demand that we take a knife to our sons as a zealous act? Was this their nod to the intense passion that is required to perform the mitzvah of circumcision?

The Torah suggests that an act is made holy by one’s intention, that the ends justify even extreme means. Pinchas succeeds in ridding the Israelites of idolatry. Elijah as well bests the prophets of Baal, bringing the people closer to monotheism. They are thus revered by our tradition.

I remain troubled. I stand appalled.

I wonder. Why must passions lead to zealous acts?

Zealousness and passion are too often intertwined. Passion is desired. Zealousness must be quelled. The knife can be an instrument of holiness or a tool for murder.

My teacher at the Shalom Hartman Institute, Dr. Israel Knohl, once remarked that monotheism is given to violence. Because it is adamant that there is only one God it promotes the destruction of other gods and occasionally, or perhaps it is better to say, too often, their worshippers. Monotheism is exacting. It can be as well ruthless.

I hold firm to its belief. I remain distant from the actions it too frequently deems holy.

And so I draw a measure of comfort from the very same prophet whose actions I abhor. Elijah’s story concludes with a beautiful estimation of where we might find God. It is not in a thunderous voice or mighty actions. "There was a great and mighty wind, splitting mountains and shattering rocks, but the Lord was not in the wind... After the earthquake—fire; but the Lord was not in the fire. And after the fire, a still, small voice." (I Kings 19)

This is the Haftarah that is often paired with this week’s portion. The rabbis offer this reading as a counterweight. We require passion, but not zealousness. Not every disagreement is a threat that necessitates radical action. Believing in one God does not require that we destroy others, or their followers. A plurality of beliefs does not negate our own firmly held convictions.

Hold fast to your own beliefs. Leave room for others’ convictions.

The Rabbis teach! If the zealot comes to seek counsel, we never instruct him to act.

Rely instead on the still, small voice.

And yet the Torah reports that Pinchas was rewarded for his actions. Here is his story. The people are gathered on the banks of the Jordan River, poised to enter the land of Israel. They have become enthralled with the religion of the Midianites, sacrificing to their god, and participating in its festivals. Moses tries to get the Israelites to stop, issuing laws forbidding such foreign practices, but they refuse to listen. God becomes enraged.

"Just then one of the Israelites came and brought a Midianite woman over to his companions... When Pinchas saw this he left the assembly and taking a spear in his hand he followed the Israelite into the chamber and stabbed both of them, the Israelite and the woman, through the belly." The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, "Pinchas has turned back My wrath from the Israelites by displaying among them his passion for Me." (Numbers 25) Pinchas' passion tempers God’s anger. Thus Pinchas renews the covenant between God and the people.

It is for this reason that Pinchas’ memory is recalled at the brit milah ceremony. As we renew the covenant through the ritual of circumcision we recall Pinchas. We then welcome the presence of the prophet Elijah who, in the future, will announce the coming of the messiah. We pray, “This is the chair of Elijah the prophet who is remembered for good.” Perhaps this young child will prove to be our people’s redeemer.

Elijah is as well a zealot. He, like Pinchas, has a violent temper and deals with non-believers with an equally heavy hand. He kills hundreds of idolaters and worshipers of Baal. So why are these the heroes we recall when we circumcise our sons? Is it possible that the rabbis saw this ritual and its demand that we take a knife to our sons as a zealous act? Was this their nod to the intense passion that is required to perform the mitzvah of circumcision?

The Torah suggests that an act is made holy by one’s intention, that the ends justify even extreme means. Pinchas succeeds in ridding the Israelites of idolatry. Elijah as well bests the prophets of Baal, bringing the people closer to monotheism. They are thus revered by our tradition.

I remain troubled. I stand appalled.

I wonder. Why must passions lead to zealous acts?

Zealousness and passion are too often intertwined. Passion is desired. Zealousness must be quelled. The knife can be an instrument of holiness or a tool for murder.

My teacher at the Shalom Hartman Institute, Dr. Israel Knohl, once remarked that monotheism is given to violence. Because it is adamant that there is only one God it promotes the destruction of other gods and occasionally, or perhaps it is better to say, too often, their worshippers. Monotheism is exacting. It can be as well ruthless.

I hold firm to its belief. I remain distant from the actions it too frequently deems holy.

And so I draw a measure of comfort from the very same prophet whose actions I abhor. Elijah’s story concludes with a beautiful estimation of where we might find God. It is not in a thunderous voice or mighty actions. "There was a great and mighty wind, splitting mountains and shattering rocks, but the Lord was not in the wind... After the earthquake—fire; but the Lord was not in the fire. And after the fire, a still, small voice." (I Kings 19)

This is the Haftarah that is often paired with this week’s portion. The rabbis offer this reading as a counterweight. We require passion, but not zealousness. Not every disagreement is a threat that necessitates radical action. Believing in one God does not require that we destroy others, or their followers. A plurality of beliefs does not negate our own firmly held convictions.

Hold fast to your own beliefs. Leave room for others’ convictions.

The Rabbis teach! If the zealot comes to seek counsel, we never instruct him to act.

Rely instead on the still, small voice.

King David's Footsteps

Several days ago, I hiked in the footsteps of King David. The words of the Bible became real. They became filled with life.

In Israel one can literally walk where our biblical heroes traveled. One can stand where Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac or where the prophet Amos admonished the Jewish people or where David composed his sweet psalms.

In the land of Israel our Bible takes shape. It is here that the soil adds flesh to our legends.

Before beginning the hike, we stood on the heights of Tel Azekah where the Israelites spied the Philistine army. It was there that our people cowered in fear before the mighty Goliath. A young David volunteered to battle the giant. He refused the offer of King Saul’s armor and spear. He thought them too cumbersome and heavy. David killed Goliath with a small pebble thrown from his slingshot. The Israelite army then routed the Philistines and the Israelites soon crowned David as king.

The legend of David and Goliath was born here, in this place....

In Israel one can literally walk where our biblical heroes traveled. One can stand where Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac or where the prophet Amos admonished the Jewish people or where David composed his sweet psalms.

In the land of Israel our Bible takes shape. It is here that the soil adds flesh to our legends.

Before beginning the hike, we stood on the heights of Tel Azekah where the Israelites spied the Philistine army. It was there that our people cowered in fear before the mighty Goliath. A young David volunteered to battle the giant. He refused the offer of King Saul’s armor and spear. He thought them too cumbersome and heavy. David killed Goliath with a small pebble thrown from his slingshot. The Israelite army then routed the Philistines and the Israelites soon crowned David as king.

The legend of David and Goliath was born here, in this place....

The Pattern of Failures

I am writing from Jerusalem where I am studying at the Shalom Hartman Institute’s Rabbinic Torah Study Seminar. I remain grateful that our congregation recognizes the need for me to deepen my learning and recharge my commitments. There is really nothing like studying with colleagues and learning from remarkable teachers, and most especially, to do so here in Jerusalem. No matter how many times I may visit this city, every time I return becomes a pilgrimage in which my spirit is renewed.

This morning I was reminded of a favorite saying of my teacher Rabbi David Hartman, may his memory be for a blessing. He often said that the Bible is an indictment of the Jewish people. Like so many of Reb David’s teachings, this appears counter intuitive. We often look to the Bible as inspiration. We hold it up time and again as the best source to motivate us to do good or for that matter, the justification to observe the Jewish holidays, or as in my present case, the cause for me to return to this holy city, year after year, or, and perhaps most especially, to re-establish sovereignty in this land after 2,000 years of wandering.

Rabbi Hartman of course saw something far different and perhaps far more in the Bible’s words. It was more about our failings than our successes. It was more about not living up to what was asked of us rather than fulfilling God’s commandments. Take the prophets for example who over and over again chastise the Jewish people for failing to live up to God’s expectations. Each and every one of them, from Amos to Isaiah, say in effect, “Do you think this is all God wants you to do!” They thundered, “It is not enough to go to services. It is not enough to light candles.”

Their exhortations can be summed up with the words, “It is not enough.”

And when one looks at the grand narrative portrayed in the Bible, as we did this morning with Micah Goodman, the author of the acclaimed book Catch-67, one realizes that the story does not culminate with the Jewish people establishing a nation in the promised land of Israel, but instead with their return to Egypt. We leave Egypt following Moses’ lead, wander the wilderness, conquer the land under Joshua, establish the rule of kings and build the Temple. But then during the years that the prophet Jeremiah prophesies, the Babylonians destroy the holy Temple and establish Gedaliah as their puppet king. He is soon assassinated by a fellow Jew.

The Book of Kings then concludes: “And all the people, young and old, and the officers of the troops set out and went to Egypt because they were afraid of the Babylonians.” (II Kings 25). History is cyclical. We were taken out of Egypt only to return to Egypt. Our powerlessness was transformed into power and then again to powerlessness.

The movement, and struggle, between power and powerlessness continues in our own age.

Back to the Bible and in particular this week’s Torah reading. Even the Five Books of Moses is not the crowning achievement of the very person who heralds its name, but instead stands as an indictment against Moses and an elucidation of his shortcomings. We read about why God does not allow him to enter the land. The people are once again complaining. There is a lot of that in the Book of Numbers. (That alone should stand as evidence of David Hartman’s teaching.) There is not enough water. God tells Moses and Aaron to instruct a rock to bring water. Moses instead hits the rock and says, “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?” (Numbers 20)

And with that, God decides that Moses does not get to enter the land. Commentators debate what was Moses’ exact sin. Was it that he hit the rock not just one time, but two? Was it instead that he became angry, again, at the people? Was it that he took credit for God’s miracle? Was it that he drew a stark line between the people and their leader and insulted them by calling them rebels?

The Bible is unclear. It is however clear that God thinks Moses’ time is done. He failed as a leader. The Five Books of Moses indicts its very own author.

Perhaps that is the Bible’s very inspiration. Failure is part and parcel to our lives.

Failure is part of our history.

Leaving Egypt and then returning to Egypt, and then leaving again and returning again, is the pattern of our destiny.

This morning I was reminded of a favorite saying of my teacher Rabbi David Hartman, may his memory be for a blessing. He often said that the Bible is an indictment of the Jewish people. Like so many of Reb David’s teachings, this appears counter intuitive. We often look to the Bible as inspiration. We hold it up time and again as the best source to motivate us to do good or for that matter, the justification to observe the Jewish holidays, or as in my present case, the cause for me to return to this holy city, year after year, or, and perhaps most especially, to re-establish sovereignty in this land after 2,000 years of wandering.

Rabbi Hartman of course saw something far different and perhaps far more in the Bible’s words. It was more about our failings than our successes. It was more about not living up to what was asked of us rather than fulfilling God’s commandments. Take the prophets for example who over and over again chastise the Jewish people for failing to live up to God’s expectations. Each and every one of them, from Amos to Isaiah, say in effect, “Do you think this is all God wants you to do!” They thundered, “It is not enough to go to services. It is not enough to light candles.”

Their exhortations can be summed up with the words, “It is not enough.”

And when one looks at the grand narrative portrayed in the Bible, as we did this morning with Micah Goodman, the author of the acclaimed book Catch-67, one realizes that the story does not culminate with the Jewish people establishing a nation in the promised land of Israel, but instead with their return to Egypt. We leave Egypt following Moses’ lead, wander the wilderness, conquer the land under Joshua, establish the rule of kings and build the Temple. But then during the years that the prophet Jeremiah prophesies, the Babylonians destroy the holy Temple and establish Gedaliah as their puppet king. He is soon assassinated by a fellow Jew.

The Book of Kings then concludes: “And all the people, young and old, and the officers of the troops set out and went to Egypt because they were afraid of the Babylonians.” (II Kings 25). History is cyclical. We were taken out of Egypt only to return to Egypt. Our powerlessness was transformed into power and then again to powerlessness.

The movement, and struggle, between power and powerlessness continues in our own age.

Back to the Bible and in particular this week’s Torah reading. Even the Five Books of Moses is not the crowning achievement of the very person who heralds its name, but instead stands as an indictment against Moses and an elucidation of his shortcomings. We read about why God does not allow him to enter the land. The people are once again complaining. There is a lot of that in the Book of Numbers. (That alone should stand as evidence of David Hartman’s teaching.) There is not enough water. God tells Moses and Aaron to instruct a rock to bring water. Moses instead hits the rock and says, “Listen, you rebels, shall we get water for you out of this rock?” (Numbers 20)

And with that, God decides that Moses does not get to enter the land. Commentators debate what was Moses’ exact sin. Was it that he hit the rock not just one time, but two? Was it instead that he became angry, again, at the people? Was it that he took credit for God’s miracle? Was it that he drew a stark line between the people and their leader and insulted them by calling them rebels?

The Bible is unclear. It is however clear that God thinks Moses’ time is done. He failed as a leader. The Five Books of Moses indicts its very own author.

Perhaps that is the Bible’s very inspiration. Failure is part and parcel to our lives.

Failure is part of our history.

Leaving Egypt and then returning to Egypt, and then leaving again and returning again, is the pattern of our destiny.

Why I'm Both Celebrating the Myth and Honoring the Anger

I wonder how Korah’s descendants describe this week’s events described in the synagogue’s weekly Torah reading. Would it be akin to the accolades we heap on Bar Kochba who led a failed a rebellion against Rome in the second century? To this day we sing of his courage when we recall Rabbi Akiva’s martyrdom on our holiest of days, Yom Kippur. Akiva was one of Bar Kochba’s greatest supporters.

Moses ruthlessly quashed Korah’s rebellion (revolution?). He killed Korah and 250 of his followers. Would my hero Moses be called a murderer by Korah’s descendants?

“Blasphemy!” one might say.

Years ago, I traveled to Israel on a UJA mission. It was during the second intifada and we were there to show our support and express our solidarity. Yitzhah Rabin was assassinated five years earlier and my companions and I were deeply traumatized by his murder and the increasingly deadly Palestinian terrorist attacks.

We mourned the soldier turned prime minister turned peace maker....

Moses ruthlessly quashed Korah’s rebellion (revolution?). He killed Korah and 250 of his followers. Would my hero Moses be called a murderer by Korah’s descendants?

“Blasphemy!” one might say.

Years ago, I traveled to Israel on a UJA mission. It was during the second intifada and we were there to show our support and express our solidarity. Yitzhah Rabin was assassinated five years earlier and my companions and I were deeply traumatized by his murder and the increasingly deadly Palestinian terrorist attacks.

We mourned the soldier turned prime minister turned peace maker....

Today's Anguish

The spies return from scouting the land of Israel. Ten return with a negative report. They say: “All the people that we saw in it were men of great size and we looked like grasshoppers to ourselves.” (Numbers 13)

Every morning I read the newspapers. Every evening I watch the TV news. During the day I read online reports.

The other day a father and daughter drowned in the Rio Grande while trying to cross the United States-Mexico border. Their names were Oscar Alberto and Valerie Martinez Ramirez. Many others have discovered a similar fate. Some fled worn torn Syria. Others ran from persecution in Sudan. Some escaped violence in Central America. Others left poverty in Venezuela.

They see in America a promise and hope.

Every morning I read the newspapers. Every evening I watch the TV news. During the day I read online reports.

And that is all I seem to do.

I offer up excuses for going about my day as if the plight of refugees and asylum seekers is normal. “But I have to buy a new pair of pants. But I have dinner plans. But I have to work out.” The problems seem enormous. They appear insurmountable. What can I do?

More! At the very least.

A father and daughter drowned at our nation’s border.

Regardless of our disagreements about immigration policy our humanity demands more of us. Our tradition asks us to do better. A father does not risk his daughter’s life out of folly. He traverses a raging river only because desperation propels him. I may not understand the specifics of his desperation, but I cannot imagine any other reason.

I have never faced such a decision. I have never needed to take such risks.

And I look like a grasshopper to myself.

I wish I could muster the strength of Joshua. I wish I could summon the courage of Caleb. They were the spies who did not see the giants. They refused to see the enormity of what stood before them. Their faith was unrivaled.

Perhaps the ten spies were realists. Perhaps the challenges they faced were in fact gigantic.

And Joshua and Caleb were idealists.

I long to hold on to their ideals. I reach for their words:

“Have no fear of them!”

I read. Have no fear. I must do more.

Every morning I read the newspapers. Every evening I watch the TV news. During the day I read online reports.

The other day a father and daughter drowned in the Rio Grande while trying to cross the United States-Mexico border. Their names were Oscar Alberto and Valerie Martinez Ramirez. Many others have discovered a similar fate. Some fled worn torn Syria. Others ran from persecution in Sudan. Some escaped violence in Central America. Others left poverty in Venezuela.

They see in America a promise and hope.

Every morning I read the newspapers. Every evening I watch the TV news. During the day I read online reports.

And that is all I seem to do.

I offer up excuses for going about my day as if the plight of refugees and asylum seekers is normal. “But I have to buy a new pair of pants. But I have dinner plans. But I have to work out.” The problems seem enormous. They appear insurmountable. What can I do?

More! At the very least.

A father and daughter drowned at our nation’s border.

Regardless of our disagreements about immigration policy our humanity demands more of us. Our tradition asks us to do better. A father does not risk his daughter’s life out of folly. He traverses a raging river only because desperation propels him. I may not understand the specifics of his desperation, but I cannot imagine any other reason.

I have never faced such a decision. I have never needed to take such risks.

And I look like a grasshopper to myself.

I wish I could muster the strength of Joshua. I wish I could summon the courage of Caleb. They were the spies who did not see the giants. They refused to see the enormity of what stood before them. Their faith was unrivaled.

Perhaps the ten spies were realists. Perhaps the challenges they faced were in fact gigantic.

And Joshua and Caleb were idealists.

I long to hold on to their ideals. I reach for their words:

“Have no fear of them!”

I read. Have no fear. I must do more.

Gossip Disfigures

How dare anyone criticize our leader!

We read: “Miriam spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman he had married.” (Numbers 12) We learn elsewhere that Moses’ wife is Zipporah. She is a Midianite. This week the Torah suggests that she is dark-skinned and therefore perhaps from Ethiopia. She is not an Israelite. Was this the basis of Miriam’s criticism of her brother Moses?

How dare he marry a foreigner!

Their brother Aaron joins the critique. He and Miriam pile on more harsh words, “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has God not spoken through us as well?” Were they jealous of their brother Moses? Did they want to lead the Israelites as well? Did they believe, as Judaism does, that everyone can have a relationship with God and that anyone, with enough wisdom and learning, can lead?

Perhaps our leader thinks too much of himself. Perhaps he denigrates the holy spark found in each and every person.

Rashi, the great medieval commentator, disagrees. He imagines Miriam criticizing her brother for neglecting his wife. Moses is singularly devoted to his mission. He is on call for God at all hours of the day and night. Miriam therefore worries about her sister in law’s well-being. She worries about her brother’s marriage and family.

I wonder. Is the best teaching offering by the very person who falls short of fulfilling its words? Rashi authored a line-by-line commentary to the entire Bible and Talmud. How did he find time for his own family? Miriam reminds us. No job is more important than family. No task, even one divinely ordained, should take precedence over those closest to us.

God apparently disagrees. Miriam is punished and stricken with leprosy. Aaron is left alone to plea for his sister, “O, my lord, account not to us the sin which we committed in our folly.”

The rabbis suggest that it was not what Miriam said but the manner in which she spoke the words. They see a parallel between this disfiguring disease and gossip. The tradition is clear. Even if the words are true they must only be spoken when absolutely necessary and then only in private. Critique becomes gossip when it finds its way into the public domain. Criticism becomes slander when it seeks to demean others rather than uplift them.

Gossip disfigures. A Hasidic story relates that it is like a feather cast to the wind. Such words can never be collected. Once gossip is shared it can never be withdrawn. The damage to a person’s reputation might never be undone. Beware of what one tweets! Judaism counsels. Gossip disfigures the gossiper.

A person’s character unravels when she or he gossips. The rabbis remind us that gossip not only belittles the person about whom we talk but also damages the person who speaks such words. Gossip denigrates everyone—even and including the person who listens.

And so we must offer prayers of contrition for all the times we resorted to gossip to entertain. We pray for all the moments we gossiped in order to give ourselves a greater sense of self-worth. We pray for all the minutes we inclined our ears to the gossip that others shared. We pray with Moses, “O God, pray, heal her.”

Heal us!

We read: “Miriam spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman he had married.” (Numbers 12) We learn elsewhere that Moses’ wife is Zipporah. She is a Midianite. This week the Torah suggests that she is dark-skinned and therefore perhaps from Ethiopia. She is not an Israelite. Was this the basis of Miriam’s criticism of her brother Moses?

How dare he marry a foreigner!

Their brother Aaron joins the critique. He and Miriam pile on more harsh words, “Has the Lord spoken only through Moses? Has God not spoken through us as well?” Were they jealous of their brother Moses? Did they want to lead the Israelites as well? Did they believe, as Judaism does, that everyone can have a relationship with God and that anyone, with enough wisdom and learning, can lead?

Perhaps our leader thinks too much of himself. Perhaps he denigrates the holy spark found in each and every person.

Rashi, the great medieval commentator, disagrees. He imagines Miriam criticizing her brother for neglecting his wife. Moses is singularly devoted to his mission. He is on call for God at all hours of the day and night. Miriam therefore worries about her sister in law’s well-being. She worries about her brother’s marriage and family.

I wonder. Is the best teaching offering by the very person who falls short of fulfilling its words? Rashi authored a line-by-line commentary to the entire Bible and Talmud. How did he find time for his own family? Miriam reminds us. No job is more important than family. No task, even one divinely ordained, should take precedence over those closest to us.

God apparently disagrees. Miriam is punished and stricken with leprosy. Aaron is left alone to plea for his sister, “O, my lord, account not to us the sin which we committed in our folly.”

The rabbis suggest that it was not what Miriam said but the manner in which she spoke the words. They see a parallel between this disfiguring disease and gossip. The tradition is clear. Even if the words are true they must only be spoken when absolutely necessary and then only in private. Critique becomes gossip when it finds its way into the public domain. Criticism becomes slander when it seeks to demean others rather than uplift them.

Gossip disfigures. A Hasidic story relates that it is like a feather cast to the wind. Such words can never be collected. Once gossip is shared it can never be withdrawn. The damage to a person’s reputation might never be undone. Beware of what one tweets! Judaism counsels. Gossip disfigures the gossiper.

A person’s character unravels when she or he gossips. The rabbis remind us that gossip not only belittles the person about whom we talk but also damages the person who speaks such words. Gossip denigrates everyone—even and including the person who listens.

And so we must offer prayers of contrition for all the times we resorted to gossip to entertain. We pray for all the moments we gossiped in order to give ourselves a greater sense of self-worth. We pray for all the minutes we inclined our ears to the gossip that others shared. We pray with Moses, “O God, pray, heal her.”

Heal us!

Making Peace

The Ktav Sofer, a leading nineteenth century Hungarian rabbi, comments: “Peace begins in the home, then extends to the community, and finally to all the world.”

It is a fascinating lesson. Often we speak about bringing peace to the world but forget about making peace with those who stand closest to us. We give lofty speeches and sermons (rabbi!) about making peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, or between Democrats and Republicans but neglect making peace with those we profess love. But such grandiose endeavors are impossible if we do not begin with a foundation of peace in our personal relationships.

If couples argue at home, then they often bring divisiveness to work. If parents yell at their children, then their children bring anger to school.

We cannot make peace if we don’t feel at peace. If our interactions with others are rife with conflict and discord then how can we bring peace or for that matter, negotiate peace? Judaism has long recognized the centrality of peace. It teaches about its necessity. Shalom bayit, peace in the home, is of paramount importance. Other values take second to preserving it.

And this is why so many of our prayers speak of peace. The central prayer we recite whenever we gather concludes with a prayer for peace. The Amidah may offer a litany of requests: for health, forgiveness and justice to name a few, but we always conclude with the words: “Blessed are You Adonai who blesses Your people Israel with peace.” We conclude as well the Blessing after Meals with the prayer: “Oseh shalom bimromav…May the One who makes peace in the high heavens make peace for us, for all Israel and all who inhabit the earth.” The Kaddish also concludes with these same words.

We pray for peace so we might have the strength to bring peace.

This week we learn the words for the priestly blessing. These are the words I am often privileged to recite at baby namings, bnai mitzvah and weddings. “May the Lord bless you and keep you! May the light of the Lord’s face shine upon you and be gracious to you! May you always find God’s presence in your life and blessed with shalom, peace.”

These are also the words that parents recite when blessing their children at the Shabbat and holiday dinner table. We begin our festive meals by asking God to bring peace to those we most treasure: our children. We conclude our meal by asking God to bring peace to our people and then to the world.

Perhaps the great Hungarian rabbi is correct. Peace must begin in the home. Then it extends to the community and finally we hope, to all the world.

I offer this suggestion. Try blessing your children at home. It might bring an additional measure of peace to your home and your most prized relationships.

And you never know. It could even be the beginning of bringing peace to the world.

It is a fascinating lesson. Often we speak about bringing peace to the world but forget about making peace with those who stand closest to us. We give lofty speeches and sermons (rabbi!) about making peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, or between Democrats and Republicans but neglect making peace with those we profess love. But such grandiose endeavors are impossible if we do not begin with a foundation of peace in our personal relationships.

If couples argue at home, then they often bring divisiveness to work. If parents yell at their children, then their children bring anger to school.

We cannot make peace if we don’t feel at peace. If our interactions with others are rife with conflict and discord then how can we bring peace or for that matter, negotiate peace? Judaism has long recognized the centrality of peace. It teaches about its necessity. Shalom bayit, peace in the home, is of paramount importance. Other values take second to preserving it.

And this is why so many of our prayers speak of peace. The central prayer we recite whenever we gather concludes with a prayer for peace. The Amidah may offer a litany of requests: for health, forgiveness and justice to name a few, but we always conclude with the words: “Blessed are You Adonai who blesses Your people Israel with peace.” We conclude as well the Blessing after Meals with the prayer: “Oseh shalom bimromav…May the One who makes peace in the high heavens make peace for us, for all Israel and all who inhabit the earth.” The Kaddish also concludes with these same words.

We pray for peace so we might have the strength to bring peace.

This week we learn the words for the priestly blessing. These are the words I am often privileged to recite at baby namings, bnai mitzvah and weddings. “May the Lord bless you and keep you! May the light of the Lord’s face shine upon you and be gracious to you! May you always find God’s presence in your life and blessed with shalom, peace.”

These are also the words that parents recite when blessing their children at the Shabbat and holiday dinner table. We begin our festive meals by asking God to bring peace to those we most treasure: our children. We conclude our meal by asking God to bring peace to our people and then to the world.

Perhaps the great Hungarian rabbi is correct. Peace must begin in the home. Then it extends to the community and finally we hope, to all the world.

I offer this suggestion. Try blessing your children at home. It might bring an additional measure of peace to your home and your most prized relationships.

And you never know. It could even be the beginning of bringing peace to the world.

The Torah of Competing Ideas

People often think the Torah speaks with one voice. They believe it provides answers. They think it is a guide laying out exactly how we might discern which ideas are winners and which losers, which duties are most important and which less. It does not.

Likewise people think that governing is about winning and losing, about voting to determine what is most important and least. It is not.

Democracies are instead sustained by compromise. They thrive when we learn how to live alongside those who hold competing ideas.

In our American system of government, Democrats and Republicans are supposed to spend their years of service hammering out compromises. Congressional leaders from opposing parties are intended to get together and debate, and even argue vociferously. But then they are supposed to offer the country a compromise agreement around which the majority of citizens can rally.

Most Americans agree, for example, that our current immigration system needs fixing. And yet we are unable to come to any agreement. Our leaders shout their beliefs; they hue to their party’s talking points rather than offering compromise proposals. This is because our leaders do not lead. They do not model compromise. They do not say, “Here is a plan to reform our immigration system with which I mostly agree.”

Instead we retreat to the comfort of the like-minded. We remain loyal to ideology and devoted to our own political opinions. We measure leaders by the metric of ideological purity. We believe that compromise signifies poor leadership. We therefore remain trapped in an age of stonewalling, executive orders and emergency powers.

Our system was designed however not so that one ideology would win the day but so that pieces of as many ideologies as possible would have their say. We have forgotten that this was always the intention of American government. It was about compromise. It was about getting to be right some of the time, not all of the time.

Democracies are breaking under the weight of more and more people, most especially our leaders, saying, “I only want to talk to and listen to those with whom I agree.”

In Israel as well its system is faltering. There, compromise is supposed to be worked out when negotiating a coalition agreement. In Israel’s multi-party system no one ever gets a majority of votes and so the leading party must cobble together enough other parties to reach at least sixty-one seats. Knesset members must do much of the hard work of hammering out compromises in order to become part of the ruling coalition.

Never before has Israel had to call elections a few months after an election. And yet this is exactly what happened last week. Why?

It is for the exact same reason that American leaders are unable to achieve meaningful compromise on the many challenges facing our own nation and the world. Israeli leaders were unable to compromise. They forgot that every coalition is imperfect. A leader might be able to be right on one issue but wrong on another. Israel, and Israeli politics especially, was always about holding as many different philosophies together while still clinging to a shared devotion to the same nation.

Today, political leaders instead held fast to their ideologies. Disagreement is now couched as disloyalty. Our systems are breaking.

And so I turn to my Torah. I look toward the celebration of Shavuot when we will once again give thanks for the revelation at Sinai.

The Rabbis comment: Had only one of the six hundred thousand been absent when the Israelites stood at Mount Sinai, the Torah would not have been given.

I recall. The Torah was not given to Moses alone. It was instead revealed to hundreds of thousands.

Rabbi Aaron Halevi, a medieval commentator adds: It is for this reason that the Torah was given to six hundred thousand people. It was the will of the Holy One, blessed be God, that the Torah be accepted by all factions, and the six hundred thousand included all factions and opinions.

We are only one people when all factions and opinions and ideas are welcomed. We are only one nation when all ideas and philosophies stand alongside each other. We must work to recapture this foundation. We must strive to renew this revelation.

Then and only then can we recover Sinai.

Likewise people think that governing is about winning and losing, about voting to determine what is most important and least. It is not.

Democracies are instead sustained by compromise. They thrive when we learn how to live alongside those who hold competing ideas.

In our American system of government, Democrats and Republicans are supposed to spend their years of service hammering out compromises. Congressional leaders from opposing parties are intended to get together and debate, and even argue vociferously. But then they are supposed to offer the country a compromise agreement around which the majority of citizens can rally.

Most Americans agree, for example, that our current immigration system needs fixing. And yet we are unable to come to any agreement. Our leaders shout their beliefs; they hue to their party’s talking points rather than offering compromise proposals. This is because our leaders do not lead. They do not model compromise. They do not say, “Here is a plan to reform our immigration system with which I mostly agree.”

Instead we retreat to the comfort of the like-minded. We remain loyal to ideology and devoted to our own political opinions. We measure leaders by the metric of ideological purity. We believe that compromise signifies poor leadership. We therefore remain trapped in an age of stonewalling, executive orders and emergency powers.

Our system was designed however not so that one ideology would win the day but so that pieces of as many ideologies as possible would have their say. We have forgotten that this was always the intention of American government. It was about compromise. It was about getting to be right some of the time, not all of the time.

Democracies are breaking under the weight of more and more people, most especially our leaders, saying, “I only want to talk to and listen to those with whom I agree.”

In Israel as well its system is faltering. There, compromise is supposed to be worked out when negotiating a coalition agreement. In Israel’s multi-party system no one ever gets a majority of votes and so the leading party must cobble together enough other parties to reach at least sixty-one seats. Knesset members must do much of the hard work of hammering out compromises in order to become part of the ruling coalition.

Never before has Israel had to call elections a few months after an election. And yet this is exactly what happened last week. Why?

It is for the exact same reason that American leaders are unable to achieve meaningful compromise on the many challenges facing our own nation and the world. Israeli leaders were unable to compromise. They forgot that every coalition is imperfect. A leader might be able to be right on one issue but wrong on another. Israel, and Israeli politics especially, was always about holding as many different philosophies together while still clinging to a shared devotion to the same nation.

Today, political leaders instead held fast to their ideologies. Disagreement is now couched as disloyalty. Our systems are breaking.

And so I turn to my Torah. I look toward the celebration of Shavuot when we will once again give thanks for the revelation at Sinai.

The Rabbis comment: Had only one of the six hundred thousand been absent when the Israelites stood at Mount Sinai, the Torah would not have been given.

I recall. The Torah was not given to Moses alone. It was instead revealed to hundreds of thousands.

Rabbi Aaron Halevi, a medieval commentator adds: It is for this reason that the Torah was given to six hundred thousand people. It was the will of the Holy One, blessed be God, that the Torah be accepted by all factions, and the six hundred thousand included all factions and opinions.

We are only one people when all factions and opinions and ideas are welcomed. We are only one nation when all ideas and philosophies stand alongside each other. We must work to recapture this foundation. We must strive to renew this revelation.

Then and only then can we recover Sinai.

The Torah's Strength

This week we conclude reading the Book of Leviticus.

We read: “These are the commandments that the Lord gave Moses for the Israelite people on Mount Sinai.” And then we say what we always say after concluding one of the Torah’s five books: “Hazak hazak v’nithazek—Be strong, be strong and may we be strengthened.”

It is a curious formulation. We say these words so frequently that we rarely pause to contemplate their meaning. Why do we wish for strength when completing the reading of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy? Why do we not hope for compassion? Is not this one of the great purposes of the Torah: to bring more compassion to our broken world?

Perhaps it is because that little can be accomplished without strength. We cannot bring compassion; we cannot bring healing without strength. We require strength, and much of it, to even bring a small measure of repair to our aching world.

And why do we repeat the word “hazak—be strong”? It is because we also require strength to open up the next book of the Torah. It demands an extraordinary amount of strength, and faith, to say year in and year out that everything we need to discover about ourselves and our world can be found in these five books. What a remarkable statement of faith we affirm.

In the face of all the 21st century’s newness, and the information that can now be gained from our iPhones or by just staring at our computer screens, we say something countercultural and perhaps even counterintuitive. We shout: more can be learned from these ancient words that we still stubbornly chant in a language we continue to struggle to understand. More truths can be gleaned from words written in a seemingly arcane way on a parchment that is so obviously removed from our fast paced digital world.

Tomorrow’s truth can be uncovered in yesterday’s words.

Reading the Torah requires the strength to say that sometimes doing something the old-fashioned way is the right way—or at the very least, can lead us to the right answers or perhaps even better to say, the right questions. Asking the right questions are the beginning to finding the correct path.

I very much doubt these words meant the same thing to the rabbis who long ago added this formula to the conclusion of reading a Torah’s book, but it is what they can mean to us today.

And why do we conclude this formula with the first person plural word “nithazek—may we be strengthened”? That answer may very well be the same as it always was. We are unified by the Torah. Our community is strengthened by the Torah reading. The Jewish world is brought together by this ritual. Every synagogue throughout the world is reading the same Torah portion.

For at least this very brief moment we are all on the same page. While we may be interpreting it in radically different ways we are unified by the words we chant. Jews everywhere begin with these same verses. The unity that too often eludes us is found on the parchment that is unrolled before us.

We are strengthened by the Torah. We are unified by this sacred scroll. We may very well feel divided on Thursday but on Shabbat morning we are brought together by this act of reading from the scroll. When the Torah scroll is lifted we become one people. Perhaps this is only momentary, but we are unified nonetheless.

We hope and pray. May this unity continue to blossom.

Hazak hazak v’nithazek!

We read: “These are the commandments that the Lord gave Moses for the Israelite people on Mount Sinai.” And then we say what we always say after concluding one of the Torah’s five books: “Hazak hazak v’nithazek—Be strong, be strong and may we be strengthened.”

It is a curious formulation. We say these words so frequently that we rarely pause to contemplate their meaning. Why do we wish for strength when completing the reading of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy? Why do we not hope for compassion? Is not this one of the great purposes of the Torah: to bring more compassion to our broken world?

Perhaps it is because that little can be accomplished without strength. We cannot bring compassion; we cannot bring healing without strength. We require strength, and much of it, to even bring a small measure of repair to our aching world.

And why do we repeat the word “hazak—be strong”? It is because we also require strength to open up the next book of the Torah. It demands an extraordinary amount of strength, and faith, to say year in and year out that everything we need to discover about ourselves and our world can be found in these five books. What a remarkable statement of faith we affirm.

In the face of all the 21st century’s newness, and the information that can now be gained from our iPhones or by just staring at our computer screens, we say something countercultural and perhaps even counterintuitive. We shout: more can be learned from these ancient words that we still stubbornly chant in a language we continue to struggle to understand. More truths can be gleaned from words written in a seemingly arcane way on a parchment that is so obviously removed from our fast paced digital world.

Tomorrow’s truth can be uncovered in yesterday’s words.

Reading the Torah requires the strength to say that sometimes doing something the old-fashioned way is the right way—or at the very least, can lead us to the right answers or perhaps even better to say, the right questions. Asking the right questions are the beginning to finding the correct path.

I very much doubt these words meant the same thing to the rabbis who long ago added this formula to the conclusion of reading a Torah’s book, but it is what they can mean to us today.

And why do we conclude this formula with the first person plural word “nithazek—may we be strengthened”? That answer may very well be the same as it always was. We are unified by the Torah. Our community is strengthened by the Torah reading. The Jewish world is brought together by this ritual. Every synagogue throughout the world is reading the same Torah portion.

For at least this very brief moment we are all on the same page. While we may be interpreting it in radically different ways we are unified by the words we chant. Jews everywhere begin with these same verses. The unity that too often eludes us is found on the parchment that is unrolled before us.

We are strengthened by the Torah. We are unified by this sacred scroll. We may very well feel divided on Thursday but on Shabbat morning we are brought together by this act of reading from the scroll. When the Torah scroll is lifted we become one people. Perhaps this is only momentary, but we are unified nonetheless.

We hope and pray. May this unity continue to blossom.

Hazak hazak v’nithazek!

Memorial Day Remembrance

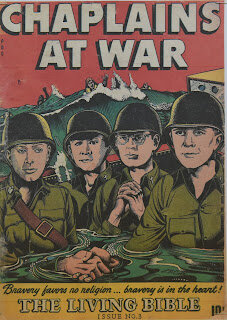

On this Memorial Day I wish to remember four chaplains. Here is their story.

On the evening of February 2, 1943 the US transport ship, Dorchester, along with two other ships, was sailing through the icy waters off the coast of Newfoundland, only 150 miles from its base in Greenland. A German U-boat spotted the ships and fired torpedoes at the Dorchester. The ship was struck. Almost immediately the captain ordered the surviving sailors to abandon ship. Within twenty minutes the ship would sink.

It was in those minutes that these chaplains became heroes. Panic and chaos set in on the Dorchester. The blast had killed hundreds. Countless were seriously wounded. Survivors groped in the darkness. Men jumped into the icy waters of the Atlantic. Others scrambled onto the lifeboats, overcrowding them and nearly capsizing the small boats.

According to survivors, four men instilled calm. They were four Army chaplains: Lt. George L. Fox, a Methodist minister; Lt. John P. Washington, a Roman Catholic priest; Lt. Clark V. Poling, a Dutch Reformed minister; and Lt. Alexander D. Goode, a rabbi. Quickly and quietly the four chaplains spread out among the sailors. There they tried to calm the frightened, tend to the wounded and guide the disoriented to safety. They offered prayers for the dying and encouragement to the living.

One survivor found himself swimming in oil-drenched ocean water surrounded by floating dead bodies and debris. Private Bednar recalled, “I could hear men crying, pleading and praying. I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.”

Another, Petty Officer John Mahoney, recalled trying to reenter his cabin. Rabbi Goode stopped him. The sailor was concerned about forgetting his winter gloves. Goode responded, “Never mind. I have two pairs.” The rabbi gave Mahoney his own gloves.

By this time, most of the sailors had scrambled topside. The chaplains opened a storage locker and began distributing life jackets. When there were no more lifejackets in the storage room, the chaplains removed theirs and gave them to four frightened young men.

As the ship began to sink, survivors in nearby rafts reported that they saw the four chaplains with their arms linked together, supporting each other against the slanting deck. Their voices could also be heard offering prayers. It is said that some Jewish sailors reported hearing the singing of the Shema. Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai echad--Hear O Israel the Lord our God the Lord is one!

During WWII many soldiers sacrificed their lives in order to conquer evil. Some stories have become well known. Others less. A rabbi, priest and two ministers did not fight the Nazis with weapons. Instead they stood together and helped to conquer fear.

I do not wish for more to die defending our nation. I did not wish to add more names to our Memorial Day litany.

Today I recall the memory of these four chaplains. Their brotherhood represents what is so great, and even unique, about our country. Standing arm in arm we can indeed conquer fear.

On the evening of February 2, 1943 the US transport ship, Dorchester, along with two other ships, was sailing through the icy waters off the coast of Newfoundland, only 150 miles from its base in Greenland. A German U-boat spotted the ships and fired torpedoes at the Dorchester. The ship was struck. Almost immediately the captain ordered the surviving sailors to abandon ship. Within twenty minutes the ship would sink.

It was in those minutes that these chaplains became heroes. Panic and chaos set in on the Dorchester. The blast had killed hundreds. Countless were seriously wounded. Survivors groped in the darkness. Men jumped into the icy waters of the Atlantic. Others scrambled onto the lifeboats, overcrowding them and nearly capsizing the small boats.

According to survivors, four men instilled calm. They were four Army chaplains: Lt. George L. Fox, a Methodist minister; Lt. John P. Washington, a Roman Catholic priest; Lt. Clark V. Poling, a Dutch Reformed minister; and Lt. Alexander D. Goode, a rabbi. Quickly and quietly the four chaplains spread out among the sailors. There they tried to calm the frightened, tend to the wounded and guide the disoriented to safety. They offered prayers for the dying and encouragement to the living.

One survivor found himself swimming in oil-drenched ocean water surrounded by floating dead bodies and debris. Private Bednar recalled, “I could hear men crying, pleading and praying. I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.”

Another, Petty Officer John Mahoney, recalled trying to reenter his cabin. Rabbi Goode stopped him. The sailor was concerned about forgetting his winter gloves. Goode responded, “Never mind. I have two pairs.” The rabbi gave Mahoney his own gloves.

By this time, most of the sailors had scrambled topside. The chaplains opened a storage locker and began distributing life jackets. When there were no more lifejackets in the storage room, the chaplains removed theirs and gave them to four frightened young men.

As the ship began to sink, survivors in nearby rafts reported that they saw the four chaplains with their arms linked together, supporting each other against the slanting deck. Their voices could also be heard offering prayers. It is said that some Jewish sailors reported hearing the singing of the Shema. Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai echad--Hear O Israel the Lord our God the Lord is one!

During WWII many soldiers sacrificed their lives in order to conquer evil. Some stories have become well known. Others less. A rabbi, priest and two ministers did not fight the Nazis with weapons. Instead they stood together and helped to conquer fear.

I do not wish for more to die defending our nation. I did not wish to add more names to our Memorial Day litany.

Today I recall the memory of these four chaplains. Their brotherhood represents what is so great, and even unique, about our country. Standing arm in arm we can indeed conquer fear.

Everything is Borrowed

Ownership is foreign to the religious mindset. Religions in general, and Judaism in particular, teach that everything is instead on loan from God. We are borrowers rather than owners.

This is true with regard to our bodies. Every human being is created in the image of God. All people contain within themselves a spark of God’s holiness. Their bodies are therefore repositories of God’s majesty. The human body is a holy vessel commanding reverence and care.

We are therefore not allowed to do whatever we want to our bodies. We are commanded to take care of them. We are obligated, for example, to eat well and exercise. To do otherwise would be a desecration of this holy vessel. To do otherwise would be to diminish God’s image. To do otherwise would be to shirk our duties and responsibilities.

While abortion is required when the mother’s life is in danger, and while I certainly believe that the mother should have far more say of what she does or does not do with her body than for instance a group of strange men, Judaism does not believe she can, or should, do whatever she wants. The body is to be cared for as if it is a Torah scroll. It is holy and but lent to us.

How we view the issues of the day hinges on the notion of whether or not we see ourselves as owners or borrowers. Better to view ourselves as custodians of a holy vessel. This is why I would suggest that the vast majority of people who nurture the frail and elderly or do the extraordinary work of hospice care are people of profound faith. Nearly all such caregivers are deeply religious.

I have come to learn that such a perspective makes this unimaginably difficult work a fraction lighter.

Such faith should also imbue how we view our possessions. If things are not viewed as earned by our hard work and our talents but instead borrowed from God, then it is likewise far easier to donate an even greater portion of our earnings to those in need. This is what Judaism seeks: a world more giving and therefore more compassionate. How does it inculcate behaviors that bring such a world closer to fruition? By teaching that everything is borrowed.

Even the land of Israel is not viewed as ours, but instead belongs to God. This is why this week we read about the sabbatical year in which the land must lie fallow on the seventh year. Land ownership is foreign to the religious mindset. A mortgage is not taken out from a bank but instead from God.

And this comes to teach that there is room not just for me, or even us, but everyone—on any land. We are stewards of the earth and tenants on God’s land.

The Torah proclaims: “The land is Mine; and you are but strangers resident with Me.” (Leviticus 25) Even the Jewish people are deemed strangers on their ancestral land.

That is the worldview that promotes more room for others. That is the mindset that inculcates the drive to share far more with neighbors. That is the perspective that teaches that we cannot do whatever we want when we want—even with our own bodies.

Imagine a world where we view everything as but lent to us. Imagine a world where there is more for everyone.

This is true with regard to our bodies. Every human being is created in the image of God. All people contain within themselves a spark of God’s holiness. Their bodies are therefore repositories of God’s majesty. The human body is a holy vessel commanding reverence and care.

We are therefore not allowed to do whatever we want to our bodies. We are commanded to take care of them. We are obligated, for example, to eat well and exercise. To do otherwise would be a desecration of this holy vessel. To do otherwise would be to diminish God’s image. To do otherwise would be to shirk our duties and responsibilities.

While abortion is required when the mother’s life is in danger, and while I certainly believe that the mother should have far more say of what she does or does not do with her body than for instance a group of strange men, Judaism does not believe she can, or should, do whatever she wants. The body is to be cared for as if it is a Torah scroll. It is holy and but lent to us.

How we view the issues of the day hinges on the notion of whether or not we see ourselves as owners or borrowers. Better to view ourselves as custodians of a holy vessel. This is why I would suggest that the vast majority of people who nurture the frail and elderly or do the extraordinary work of hospice care are people of profound faith. Nearly all such caregivers are deeply religious.

I have come to learn that such a perspective makes this unimaginably difficult work a fraction lighter.

Such faith should also imbue how we view our possessions. If things are not viewed as earned by our hard work and our talents but instead borrowed from God, then it is likewise far easier to donate an even greater portion of our earnings to those in need. This is what Judaism seeks: a world more giving and therefore more compassionate. How does it inculcate behaviors that bring such a world closer to fruition? By teaching that everything is borrowed.

Even the land of Israel is not viewed as ours, but instead belongs to God. This is why this week we read about the sabbatical year in which the land must lie fallow on the seventh year. Land ownership is foreign to the religious mindset. A mortgage is not taken out from a bank but instead from God.

And this comes to teach that there is room not just for me, or even us, but everyone—on any land. We are stewards of the earth and tenants on God’s land.

The Torah proclaims: “The land is Mine; and you are but strangers resident with Me.” (Leviticus 25) Even the Jewish people are deemed strangers on their ancestral land.

That is the worldview that promotes more room for others. That is the mindset that inculcates the drive to share far more with neighbors. That is the perspective that teaches that we cannot do whatever we want when we want—even with our own bodies.

Imagine a world where we view everything as but lent to us. Imagine a world where there is more for everyone.

Be More Religious, Do More Good

Nearly 200 years ago, Rabbi Israel Salantar, the founder of the Musar movement, a philosophy that sought to move ethics back to the center of Jewish life, told his students that he had an important job for them. They were to go out and inspect the local matzah factory to certify that its products were indeed kosher for Passover. They talked amongst themselves before their rabbi arrived. They had spent weeks studying Passover’s restrictions and pouring over the words of the Talmudic tractate detailing the holiday’s laws.

They had argued whether or not legumes should be permitted on the holiday and how to sell the hametz. One of them asked the group, “How many minutes must transpire from when the flour and water are mixed until the matzah is taken out of the oven?” “Eighteen minutes,” another shouted. (In a nutshell the technical difference between bread and matzah is about the timing. Eighteen minutes or under its matzah. Nineteen its bread—not good bread, but bread nonetheless.)

The great sage then entered the class. “We are ready for this holy task,” they said in unison. “Rabbi,” one of his students asked. “Is there something we should specifically look for there?” “Yes. Most definitely,” said Rabbi Salanter. “When you get to the factory, you will see an old woman baking matzah. The woman is poor and has a large family to support. Make sure that the factory’s owners are paying her a living wage.”

The students stared at each other in astonishment. One asked, “What about making sure the preparation and cooking take no more than eighteen minutes?” “That is really not the most important thing, my students,” Salanter said. “The most important thing is to make sure that the person who is baking this matzah is properly taken care of. If she is not then the matzah factory is not worthy of being called kosher.”

People often define religiosity in terms of ritual scrupulousness. That makes sense given this week’s portion that details all of the major Jewish holidays: Shabbat, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Passover, Shavuot and even the Omer period in which we now find ourselves. That makes sense given the importance people often ascribe to participation in Shabbat services.

On Friday evening I often hear, “Rabbi, where is everyone? Why are people not here at services? No one is practicing Judaism anymore. If we don’t make sure more people are more observant then our people are not going to be around much longer.” I usually respond: “What does being Jewish mean to you?” And they answer, “Observing Shabbat. Coming to services. Celebrating the holidays.”

I admit. I love our praying and singing. It offers me uplift. Shabbat prayer provides me the opportunity to connect with God and with people—in real time and in the real world, as opposed to the virtual world of Facebook and Instagram. It offers me a respite from the weekday worries. And when it works really well prayer helps to point me towards my ethical obligations.

Judaism does not view rituals as ends unto themselves. It does not view the Shabbat candles or the mezuzah as protective amulets that will ward away bad tidings. If people kiss the mezuzah, for example, when entering their home but then scream and yell at their family then they are missing the mezuzah’s greatest lesson. The theory is simple. If you kiss the mezuzah you are more apt to treat others with love and kindness. If you light the candles you are more likely to work to bring a measure of shalom to the world.

Rituals point to ethics.

Still it appears that an increasing number of American Jewish have become less enamored with our tradition’s rituals. They find yoga, or perhaps cycling, as more centering than Shabbat prayers.

So the question for today is can we do Jewish with lives less infused with Jewish ritual? At the very least we should expand our understanding of what it means to be religious. We should stop writing ourselves out of being religious because we do not light candles eighteen minutes before sunset or only eat matzah during Passover. We should instead ask ourselves the more challenging questions.

Do we pay our employees a living wage? Do we love the stranger? Do we give enough to tzedakah? Do we avoid speaking lashon hara—gossip? Do we treat our parents with respect?

That list is perhaps lengthier than the list of ritual commandments. It is certainly more challenging to observe than coming to services each and every Friday evening. But answer, “Yes, I do.” to even a few of these commands on even a somewhat regular basis and we can begin to call ourselves religious.

Perhaps we should become just as devout in calling our parents before Shabbat as lighting the candles. Perhaps we should be just as scrupulous with the words we speak about our neighbors as we do with the adornments of the Passover seder plate.

One day I dream of saying, “I serve the most religious congregation anyone can ever imagine. They all might not be here this Shabbat evening but they are busy making the world a better place with a word of kindness here and an extra dollar there.

They had argued whether or not legumes should be permitted on the holiday and how to sell the hametz. One of them asked the group, “How many minutes must transpire from when the flour and water are mixed until the matzah is taken out of the oven?” “Eighteen minutes,” another shouted. (In a nutshell the technical difference between bread and matzah is about the timing. Eighteen minutes or under its matzah. Nineteen its bread—not good bread, but bread nonetheless.)

The great sage then entered the class. “We are ready for this holy task,” they said in unison. “Rabbi,” one of his students asked. “Is there something we should specifically look for there?” “Yes. Most definitely,” said Rabbi Salanter. “When you get to the factory, you will see an old woman baking matzah. The woman is poor and has a large family to support. Make sure that the factory’s owners are paying her a living wage.”

The students stared at each other in astonishment. One asked, “What about making sure the preparation and cooking take no more than eighteen minutes?” “That is really not the most important thing, my students,” Salanter said. “The most important thing is to make sure that the person who is baking this matzah is properly taken care of. If she is not then the matzah factory is not worthy of being called kosher.”

People often define religiosity in terms of ritual scrupulousness. That makes sense given this week’s portion that details all of the major Jewish holidays: Shabbat, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Passover, Shavuot and even the Omer period in which we now find ourselves. That makes sense given the importance people often ascribe to participation in Shabbat services.

On Friday evening I often hear, “Rabbi, where is everyone? Why are people not here at services? No one is practicing Judaism anymore. If we don’t make sure more people are more observant then our people are not going to be around much longer.” I usually respond: “What does being Jewish mean to you?” And they answer, “Observing Shabbat. Coming to services. Celebrating the holidays.”

I admit. I love our praying and singing. It offers me uplift. Shabbat prayer provides me the opportunity to connect with God and with people—in real time and in the real world, as opposed to the virtual world of Facebook and Instagram. It offers me a respite from the weekday worries. And when it works really well prayer helps to point me towards my ethical obligations.

Judaism does not view rituals as ends unto themselves. It does not view the Shabbat candles or the mezuzah as protective amulets that will ward away bad tidings. If people kiss the mezuzah, for example, when entering their home but then scream and yell at their family then they are missing the mezuzah’s greatest lesson. The theory is simple. If you kiss the mezuzah you are more apt to treat others with love and kindness. If you light the candles you are more likely to work to bring a measure of shalom to the world.

Rituals point to ethics.

Still it appears that an increasing number of American Jewish have become less enamored with our tradition’s rituals. They find yoga, or perhaps cycling, as more centering than Shabbat prayers.

So the question for today is can we do Jewish with lives less infused with Jewish ritual? At the very least we should expand our understanding of what it means to be religious. We should stop writing ourselves out of being religious because we do not light candles eighteen minutes before sunset or only eat matzah during Passover. We should instead ask ourselves the more challenging questions.

Do we pay our employees a living wage? Do we love the stranger? Do we give enough to tzedakah? Do we avoid speaking lashon hara—gossip? Do we treat our parents with respect?

That list is perhaps lengthier than the list of ritual commandments. It is certainly more challenging to observe than coming to services each and every Friday evening. But answer, “Yes, I do.” to even a few of these commands on even a somewhat regular basis and we can begin to call ourselves religious.

Perhaps we should become just as devout in calling our parents before Shabbat as lighting the candles. Perhaps we should be just as scrupulous with the words we speak about our neighbors as we do with the adornments of the Passover seder plate.

One day I dream of saying, “I serve the most religious congregation anyone can ever imagine. They all might not be here this Shabbat evening but they are busy making the world a better place with a word of kindness here and an extra dollar there.

Israel's Ordinariness is Extraordinary

Today the State of Israel celebrates 71 years of independence. Just saying that statement is a remarkable thing to utter. Israel’s 71st. Savor those words.

For all of the challenges and missteps, the achievements and triumphs, the disappointments and missed opportunities, the unrivaled successes and countless celebrations none come close to the feeling, the remarkable gift and the sense of gratitude that Israel celebrates 71 years of independence. The dream of generations of Jews is now a reality. For 2,000 years we dreamed that we would one day return to the land of Israel. This still figures prominently in our prayers. The Seders we only recently celebrated conclude with the words L’shanah habah b’yerushalayim—next year in Jerusalem.

Today, I could say, “I am leaving tomorrow morning to fly to Israel.” I am not doing that of course, but if I were, the response would not be, “Wow. What a miracle.” But instead, “Which airline? Are you flying El Al? Are you flying out of JFK?” Another would chime in, “Don’t fly El Al. It’s the worst. People are constantly climbing over you as you are trying to sleep. You should fly Turkish Air instead.”

Others would ask, “Where are you staying?” More would then offer advice. “You should stay at the King David. It’s historic. You should spend more days in Tel Aviv. Go to Mitzpe Ramon and check out the Negev desert. Make a reservation at Zahav.” Actually Zahav is located in Philadelphia and was recently named the best restaurant in America. How remarkable is that. The best restaurant in America features Israeli cuisine.

We should take in the sheer ordinariness of these conversations.

Thousands of years ago we were almost destroyed. We then mourned the destruction of Jerusalem. And now, in our own age, we talk about visiting Israel as if it’s just another trip to another great country. We argue about flights and hotels, restaurants and sites. For all the discussions and debates we could have about Israel’s policies and the never ending conflict with the Palestinians, most recently after Hamas fired hundreds of rockets from Gaza, on this day we should breathe in not the miracle of the State of Israel but instead its ordinariness.

We wish for it to always be extraordinary, to fulfill our every dream, to live up to the prayers we sing about it, but on this day we should hold on to the ordinary. And that very ordinariness should be what takes our breath away. It is not the miracle but the ordinariness which is the fulfillment of the Zionist dream. It affirms the Declaration of Independence’s words: “This right is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations, in their own sovereign State.”